Eliezer Yudkowsky and the Unabomber Have a Lot in Common

(4,700 words)

Given that some of the newly released Epstein files contain additional communications between Epstein and Chomsky, I’ve updated my article on the topic. It also turns out that Yudkowsky and Ben Goertzel are in the Epstein files, but I’ll save that for another article!

Acknowledgments: Thanks to Remmelt Ellen for providing critical feedback on an earlier draft. That does not imply that Ellen agrees with this post. For an excellent critique of the AI company Anthropic, written by Ellen, click here.

Our main topic today concerns the surprising similarities between Eliezer Yudkowsky and Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber. As many of you know, Kaczynski was responsible for a campaign of domestic terrorism from 1978 until 1995, during which he sent home-made bombs through the mail to universities and airlines. This is why the media and FBI dubbed him the Un(iversity)-a(irline)-bomber.

In 1995, the FBI captured Kaczynski in his remote cabin near Lincoln, Montana, after Kaczynski coerced the Washington Post and New York Times into publishing a 35,000-word essay against aspects of technology. This is now called the “Unabomber Manifesto.” Kaczynski’s brother, David, recognized the writing style and reported him to authorities.

After pleading guilty to all charges, he was incarcerated in a supermax prison in Colorado, where he befriended the Oklahoma City bomber, Timothy McVeigh, whose actions Kaczynski described as “unnecessarily inhumane” (I’ll reference this again below). Kaczynski remained in prison until he committed suicide in 2023.

In his manifesto, Kaczynski rails against technology and industrialization. He also vociferously attacks leftism; he absolutely hated leftists! If the word had existed back then, he might have called himself an “anti-woke crusader.”

Some have interpreted Kaczynski as an “anarcho-primitivist,” or someone who wants humanity to return to the hunter-gatherer lifeways of our Pleistocene ancestors. But that’s not true: Kaczynski simply didn’t like industrial-era technology.

For example, he distinguished between “organization-dependent” and “small-scale” technologies: the former denotes “technology that depends on large-scale social organization.” This kind of technology cannot be reformed, he argues, given how interconnected it is. It comes as a kind of “unity,” meaning that “you can’t get rid of the ‘bad’ parts of technology and retain only the ‘good’ parts.” He gives the following example:

Progress in medical science depends on progress in chemistry, physics, biology, computer science and other fields. Advanced medical treatments require expensive, high-tech equipment that can be made available only by a technologically progressive, economically rich society. Clearly you can’t have much progress in medicine without the whole technological system and everything that goes with it.

In contrast, small-scale technology is that which “can be used by small-scale communities without outside assistance.” There are supposedly no examples of small-scale technologies being rolled back, precisely because they don’t rely on a vast network of other technologies to build and use. Since organization-dependent technology does — by definition — require such a network, sufficiently large shocks to the system can cause it to catastrophically crumble, thus leaving behind only the small-scale technologies that Kaczynski favors. For example, he writes that:

When the Roman Empire fell apart the Romans’ small-scale technology survived because any clever village craftsman could build, for instance, a water wheel, any skilled smith could make steel by Roman methods, and so forth. But the Romans’ organization-dependent technology DID regress. Their aqueducts fell into disrepair and were never rebuilt. Their techniques of road construction were lost. The Roman system of urban sanitation was forgotten, so that not until rather recent times did the sanitation of European cities equal that of Ancient Rome.

This is why reforming “the system” won’t work. We need a radical revolution, which he says “may or may not make use of violence; it may be sudden or it may be a relatively gradual process spanning a few decades.”

Kaczynski wasn’t much of an environmentalist. His primary motivation, on my reading, wasn’t to preserve the natural world, based on some notion of, e.g., biocentrism — a “value theory” that emerged in the 1970s, according to which nonhuman organisms possess intrinsic value (i.e., value in themselves) no less than humans. And he never advocated returning to the lifeways of our distant ancestors (“Back to the Pleistocene!”), as anarcho-primitivists do.

Rather, his primary concern was that the megatechnics of industrial civilization pose a dire threat to human freedom, dignity, and autonomy (his words). Hence, we need a revolution to completely decimate organization-dependent technology — the megatechnics of industrial society just mentioned — leaving behind only small-scale technologies.

Bill the Killjoy

Kaczynski’s manifesto, published with the promise that Kaczynski would desist his terrorist campaign, triggered a public debate about the consequences of advanced technology. Many people vehemently condemned Kaczynski’s homicidal actions while acknowledging that his manifesto made some compelling arguments.

One of these was a guy named Bill Joy, cofounder of Sun Microsystems who seems to have become a billionaire around 2000.1 On April 1 of that year (of all dates!), in the pages of Wired magazine (of all outlets!), Joy published a widely discussed article titled “Why the Future Doesn’t Need Us.” He writes that

From the moment I became involved in the creation of new technologies, their ethical dimensions have concerned me, but it was only in the autumn of 1998 that I became anxiously aware of how great are the dangers facing us in the 21st century. I can date the onset of my unease to the day I met Ray Kurzweil.

Kurzweil argued that the rate of technological “progress” is exponential, and hence that sentient robots are “a near-term possibility.” Joy had a personal conversation about this with Kurzweil at an event, and given how much Joy respected Kurzweil, he took this prognostication seriously.

Kurzweil then gave Joy a preprint copy of his forthcoming book The Age of Spiritual Machines, published in 1999. Joy writes that “I found myself most troubled by a passage detailing a dystopian scenario” in that book. This passage reads as follows (it’s a bit long, but worth reading in full):

First let us postulate that the computer scientists succeed in developing intelligent machines that can do all things better than human beings can do them. In that case presumably all work will be done by vast, highly organized systems of machines and no human effort will be necessary. Either of two cases might occur. The machines might be permitted to make all of their own decisions without human oversight, or else human control over the machines might be retained.

If the machines are permitted to make all their own decisions, we can’t make any conjectures as to the results, because it is impossible to guess how such machines might behave. We only point out that the fate of the human race would be at the mercy of the machines. It might be argued that the human race would never be foolish enough to hand over all the power to the machines. But we are suggesting neither that the human race would voluntarily turn power over to the machines nor that the machines would willfully seize power. What we do suggest is that the human race might easily permit itself to drift into a position of such dependence on the machines that it would have no practical choice but to accept all of the machines’ decisions. As society and the problems that face it become more and more complex and machines become more and more intelligent, people will let machines make more of their decisions for them, simply because machine-made decisions will bring better results than man-made ones. Eventually a stage may be reached at which the decisions necessary to keep the system running will be so complex that human beings will be incapable of making them intelligently. At that stage the machines will be in effective control. People won’t be able to just turn the machines off, because they will be so dependent on them that turning them off would amount to suicide.

On the other hand it is possible that human control over the machines may be retained. In that case the average man may have control over certain private machines of his own, such as his car or his personal computer, but control over large systems of machines will be in the hands of a tiny elite — just as it is today, but with two differences. Due to improved techniques the elite will have greater control over the masses; and because human work will no longer be necessary the masses will be superfluous, a useless burden on the system. If the elite is ruthless they may simply decide to exterminate the mass of humanity. If they are humane they may use propaganda or other psychological or biological techniques to reduce the birth rate until the mass of humanity becomes extinct, leaving the world to the elite. Or, if the elite consists of soft-hearted liberals, they may decide to play the role of good shepherds to the rest of the human race. They will see to it that everyone’s physical needs are satisfied, that all children are raised under psychologically hygienic conditions, that everyone has a wholesome hobby to keep him busy, and that anyone who may become dissatisfied undergoes “treatment” to cure his “problem.” Of course, life will be so purposeless that people will have to be biologically or psychologically engineered either to remove their need for the power process or make them “sublimate” their drive for power into some harmless hobby. These engineered human beings may be happy in such a society, but they will most certainly not be free. They will have been reduced to the status of domestic animals.

In Kurzweil’s book, you don’t find out until the next page that this is, in fact, an excerpt from the Unabomber Manifesto! Joy was shocked — as were most readers. This AI dystopia scenario actually seemed plausible, and perhaps something that could become our reality in the coming decades, given the exponential rate of technological development.

Kurzweil himself acknowledges that dystopia — a version of “doom” — is a very real possibility. He writes that “I was surprised how much of Kaczynskiʹs manifesto I agreed with,” as it constitutes a “persuasive … exposition on the psychological alienation, social dislocation, environmental injury, and other injuries and perils of the technological age.”

However, Kurzweil disagreed with Kaczynski that technologization and industrialization have been overall net negative — i.e., that there’s more bad than good associated with this transformation. Furthermore, he writes that

although [Kaczynski] makes a compelling case for the dangers and damages that have accompanied industrialization his proposed vision is neither compelling nor feasible. After all, there is too little nature left to return to, and there are too many human beings. For better or worse, we’re stuck with technology.

Transhumanists Vs. Luddites

This brings us to a very important development that crucially shaped the TESCREAL movement, as well as the ongoing race to build ASI, or artificial superintelligence.

Note that the ASI race emerged out of the TESCREAL movement in the 2010s, thanks to the 2010 Singularity Summit, which enabled Demis Hassabis — cofounder of DeepMind — to solicit funding from Thiel. That got the first major company with the explicit goal of creating ASI off the ground.The situation was this:

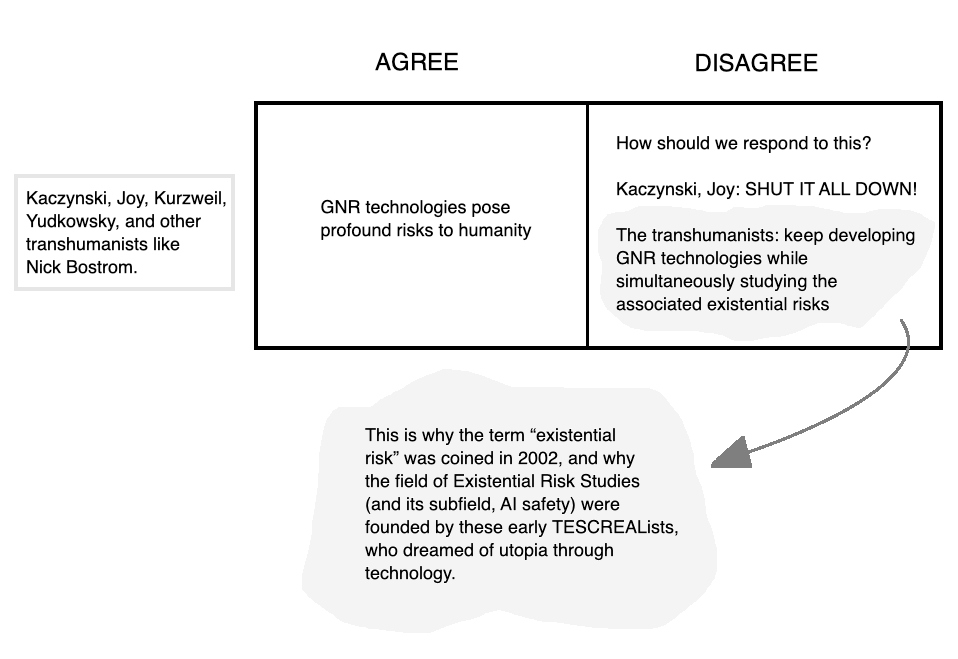

Everyone — Kurzweil, Joy, and Kaczynski, as well as a young Yudkowsky — agreed that the dangers of emerging technology are unprecedented and profound. But not everyone agreed about how we should respond to this apparent fact.

Joy argued that the only way to avoid a dystopian future like the one Kaczynski outlined is to impose strict moratoriums on entire domains of emerging science and technology through some sort of global treaty — perhaps on the model of “the 1972 Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) and the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC).” He identified three problematic domains in particular: genetic engineering, molecular nanotechnology, and artificial intelligence, which he referred to using the acronym “GNR,” for “genetics, nanotech, and robotics.” In other words, Joy’s preferred response was “broad relinquishment” — basically, shut it all down, now!

This is very similar to Kaczynski’s revolutionary proposal: to broadly relinquish organization-dependent technologies to save humanity from a dangerous future in which we might lose everything that matters to us.

In contrast, Kurzweil and Yudkowsky were diehard transhumanists who claimed that, if GNR technologies are developed the right way, they could usher in a veritable utopia of posthuman immortality, superintelligence, and perfection. Once the Singularity happens, we will fully merge with machines and initiate a colonization explosion that floods the universe with the “light of consciousness,” such that the universe itself “wakes up,” to quote Kurzweil. This means that failing to develop GNR technologies is not an option. It would be tantamount to giving up on utopia forever, which is unacceptable!

Consequently, these transhumanists proposed an alternative response to what everyone agreed about: that GNR technologies are existentially risky. Instead of relinquishing entire domains of science and technology, we should instead found a new field dedicated to studying the associated risks with the goal of neutralizing them — so we can keep our technological cake and eat it, too.

This is how the field of Existential Risk Studies started. In 2001, the arch-transhumanist Nick Bostrom wrote a paper introducing the concept of an “existential risk,” which refers to any event that would prevent us from successfully transitioning to a utopian posthuman world. (This paper was then published in 2002.) The study of existential risks is thus an effort to ensure that GNR technologies usher in paradise rather than universal annihilation.

For a critique of how the ideologies underlying and motivating Existential Risk Studies could themselves pose immense dangers to humanity, see this article of mine in Aeon. See also my series of articles on Silicon Valley pro-extinctionism, which is intimately bound up with the notion of existential risks.

I myself was one of the most prolific contributors to the existential risk literature, and this is exactly how I understood the situation. I had read Joy’s article and Kurzweil’s books, and came to agree with Kurzweil that ASI is inevitable — someone somewhere at some point is going to develop it — so broad relinquishment is infeasible. It just won’t work. Rather, we need to buckle in and carefully examine the nature and etiology of existential risks, utilizing whatever tools we have to reduce the probability of an existential catastrophe as we push forward toward utopia.

Shut It All Down!

In a 2008 article, which I believe was written a few years earlier, Yudkowsky writes the following about the goals of his Singularity Institute (now MIRI):

Concern about the risks of future AI technology has led some commentators, such as Sun co-founder Bill Joy, to suggest the global regulation and restriction of such technologies. However, appropriately designed AI could offer similarly enormous benefits.

An AI smarter than humans could help us eradicate diseases, avert long-term nuclear risks, and live richer, more meaningful lives. Further, the prospect of those benefits along with the competitive advantages from AI would make a restrictive global treaty difficult to enforce.

The Singularity Institute’s primary approach to reducing AI risks has thus been to promote the development of AI with benevolent motivations that are reliably stable under self-improvement, what we call “Friendly AI.”2

For a detailed look at Yudkowsky’s long history of patently ridiculous ideas (such as that it might be okay to murder children up to the age of 6), see this newsletter article of mine.

Once again: utopia lies on the horizon, but we can’t get there without GNR technologies — especially ASI. So, what should we do? Establish organizations like the Singularity Institute to figure out how to make an ASI that doesn’t annihilate us but instead leads us to utopia.

From 2002 (when Bostrom founded Existential Risk Studies) until recently, Yudkowsky and his Rationalist-cult colleagues had been busy working away toward a solution to this problem, sometimes called the “value-alignment problem.” This is the central task of “AI safety,” which is a direct offshoot of Existential Risk Studies. Put differently, it’s the branch or subfield of Existential Risk Studies specifically focused on ASI.

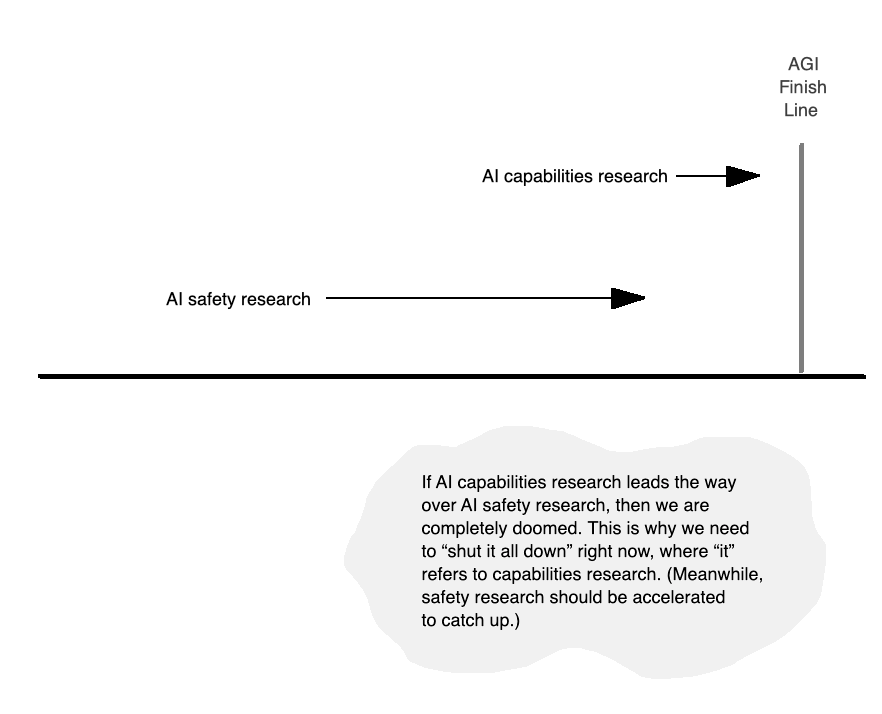

However, one failure after another has led Yudkowsky and his doomer buddies to conclude that the value-alignment problem may take decades to solve — perhaps even centuries. Meanwhile, AI capabilities research — the effort to actually build an ASI, in contrast to AI safety’s goal of ensuring that the ASI is value-aligned — continues at something like an exponential pace. Or so they claim.

This leaves us in an immensely dangerous situation: companies like DeepMind might build an ASI before we know how to control it. And if we can’t control it, then the default outcome will be doom for everyone on Earth.

Yudkowsky Comes Full Circle

Consequently, Yudkowsky has started to adopt a position strikingly similar to Joy’s: the only feasible option right now is to shut it all down, as Yudkowsky argued in a 2023 article in TIME magazine. Whereas in 2008 he was claiming that “a restrictive global treaty” would be “difficult to enforce” — it is, essentially, a nonstarter — by 2023 he’s explicitly arguing for a global treaty to prevent any company anywhere on Earth from developing ASI within the foreseeable future.3

This is essentially a broad relinquishment proposal because Yudkowsky is saying that the entire field of AI capabilities research must be halted immediately and indefinitely. With another several decades, or perhaps a few centuries, AI safety research can finally catch up to capabilities research, at which point we should proceed to build ASI — but only once we’re extremely sure that the outcome will be utopia rather than doom.

There are also echoes of Kaczynski here. As my friend Remmelt Ellen points out (personal communication),

both Kaczynski and Yudkowsky want to achieve ultimate freedom – and to not be inhibited by what those (normie) feminists had to say. Both are libertarians with anti-woke inclinations. They just ended up with radically different conceptions of what “being free” versus “being locked up” means. For Kaczynski, it was being caged by the technological system. For Yudkowsky and other transhumanists, it’s being caged in a mortal suboptimal human body (not having the right kind of technological innovation).

Remmelt adds that both are also “white privileged guys who think they can play with the lives of others for their idealized freedoms.”

Here’s what I would add: Kaczynski saw humanity as confronting an apocalyptic moment in which the only option to save humanity from existentially disastrous technology is to overthrow the reigning paradigm — industrial society. Yudkowsky similarly argues that we’re in an apocalyptic moment where the only option left is to overthrow the current configuration of our technological milieu, whereby AI capabilities research is racing toward the ASI finish line much faster than AI safety research. Something radical and drastic has to change, now.

To be clear, Yudkowsky isn’t calling for the overthrow of our entire industrial system. But he is advocating for a major system within that system to be fully and indefinitely dismantled. Consider that the ASI race is backed by more than $1.5 trillion, as of 2025. It’s led by some of the most powerful tech billionaires on the planet — many of whom have direct links to the most powerful political figures in the world like Trump and JD Vance. Such figures will vigorously resist any deceleration of the ASI race, in part because they think we’re in an AI game of chicken with our geopolitical rival, China. Furthermore, this race has become a sizable portion of the US economy — “a little under 40% of average real GDP growth” during 2025, according to CNBC — and if the “AI bubble” were to burst, it could plunge the entire economy into a great recession, or even depression.

An immediate stop to the ASI race would require a fundamental shift away from the currently entrenched social, political, and economic system-state. It would amount to a radical pivot from the status quo. Yet, if we fail to do this in the coming months or years, quite literally everyone on Earth will die, Yudkowsky claims.4

“Solution: Be Ted Kaczynski”

There are even more striking similarities. These relate to the strategies or tactics that might be employed to save humanity from technology gone awry. In the aforementioned TIME article, Yudkowsky argues that states should be willing to engage in targeted military strikes against “rogue data centers” to prevent ASI from being built in the near future. If anyone violates this global treaty, we should respond as if it’s an existential threat to one’s country.

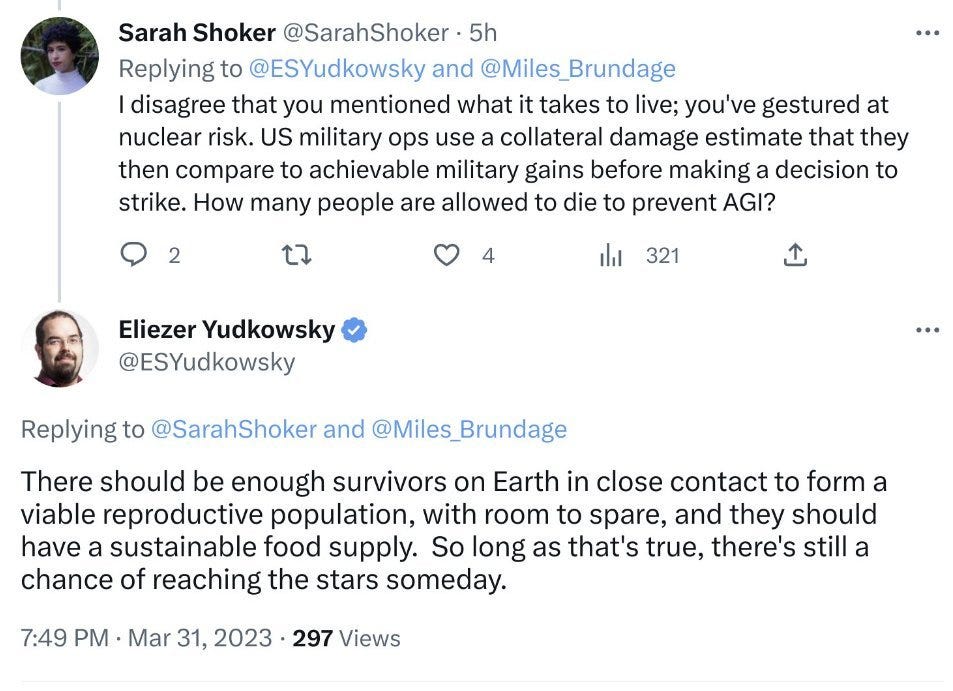

He says militaries should do this even at the risk of triggering a thermonuclear war. When asked on social media, “How many people are allowed to die to prevent AGI” from being built near-term, he said basically everyone on Earth:

There should be enough survivors on Earth in close contact to form a viable reproductive population, with room to spare, and they should have a sustainable food supply. So long as that’s true, there’s still a chance of reaching the stars someday.

Since the minimum viable human population may be as low as 150 people, that means that roughly 8.2 billion people are “allowed” to die to protect the utopian fantasies that a value-aligned ASI could, they claim, realize.

On another occasion, he was asked about “bombing the Wuhan center studying pathogens” to prevent the Covid-19 pandemic, to which he responded that it’s a “great question” and “if I can do it secretly, I probably do and then throw up a lot.” This makes one wonder whether he’d be willing to bomb AI laboratories to prevent an ASI catastrophe — an outcome almost infinitely worse, from the TESCREAL perspective, than the pandemic.

He’s endorsed property damage to prevent the creation of ASI, and once said that he’d be willing to sacrifice “all of humanity” to create god-like ASI that flit about the universe “to make the stars cities.”

That being said, the eschatology of Yudkowsky’s view is clearly different from that of Kaczynski’s. The latter wants a global return to communities built around small-scale technologies, whereas Yudkowsky wants cosmic-scale megatechnics by developing ASI the “right way.” Kaczynski saw our current path as a complete dead-end — hence, the need for a revolution that demolishes industrial society — whereas Yudkowsky imagines there being only one way forward: across a narrowing bridge of further technologization that might collapse at any moment if we’re not extremely careful. Yet Yudkowsky has spoken approvingly of strategies and tactics not that different from Kaczynski’s.

In fact, his endorsement of military strikes at the risk of starting a nearly extinctional thermonuclear war goes way beyond what Kaczynski would have ever endorsed. Recall Kaczynski’s comments about the domestic terrorism of McVeigh, which he described as “inhumane.” Although Yudkowsky hasn’t committed any acts of violence — and let’s hope that remains the case — he’s flirting with scenarios far more extreme than anything Kaczynski came close to approving.

Even more, Yudkowsky’s apocalyptic rhetoric and statements about risking nuclear war, bombing Wuhan, etc. have shifted the Overton window within the Rationalist cult. Consider an AI safety workshop at the end of 2022, shortly after OpenAI freaked out the Rationalists by releasing ChatGPT. This workshop was put together by three people in the TESCREAL movement, one of whom went on to work for Yudkowsky’s Thiel- and Epstein-funded organization MIRI. As I wrote in an article for Truthdig:

Although MIRI was not directly involved in the workshop, Yudkowsky reportedly attended a workshop afterparty.

Under the heading “produce aligned AI before unaligned [AI] kills everyone,” the meeting minutes indicate that someone suggested the following: “Solution: be Ted Kaczynski.” Later on, someone proposed the “strategy” of “start building bombs from your cabin in Montana,” where Kaczynski conducted his campaign of domestic terrorism, “and mail them to DeepMind and OpenAI lol.” This was followed a few sentences later by, “Strategy: We kill all AI researchers.”

Participants noted that if such proposals were enacted, they could be “harmful for AI governance,” presumably because of the reputational damage they might cause to the AI safety community. But they also implied that if all AI researchers are killed, this could mean that AGI doesn’t get built. And foregoing AGI, if properly aligned, would mean that we “lose a lot of potential value of good things.”

Be Ted Kaczynski and start sending bombs from your Montana cabin to save humanity! The circle back to Kaczynski — going beyond Joy’s non-violent broad relinquishment proposal — is complete. As Remmelt writes:

While Yudkowsky has not performed actions like Ted, he is also an ideologue pushing for his notion of ultimate freedom that plays with the lives of people. And Eliezer’s past rhetoric risks inspiring Kaczynski-style actors. What started with Ted Kaczynski ended with Yudkowsky inspiring Kaczynski-style thinking.

Dario Amodei and Bill Joy

This is a fascinating narrative arc, in my opinion. Some of the very same transhumanists who scoffed at Joy’s proposal are now arguing that we must “shut it all down.” A subset of these transhumanists, including Yudkowsky, are increasingly discussing and thus normalizing talk of violence to achieve their aims of stopping AI capabilities research.

As it happens, in a rambling post on X, in which Yudkowsky bizarrely claims he never knowingly engaged in statutory rape [spits coffee], he also says he never read the Unabomber Manifesto. That may be true, but it doesn’t change the fact that Yudkowsky and his Rationalist cult share many notable similarities with Kaczynski and his radical brand of neo-Luddism.

It’s also worth noting that Dario Amodei, cofounder of Anthropic, recently published an article titled “The Adolescence of Technology” in which he references both Joy and Kaczynski. He says that “I originally read Joy’s essay 25 years ago, when it was written, and it had a profound impact on me,” adding that

then and now, I do see it as too pessimistic — I don’t think broad “relinquishment” of whole areas of technology, which Joy suggests, is the answer — but the issues it raises were surprisingly prescient, and Joy also writes with a deep sense of compassion and humanity that I admire.

Amodei doesn’t see relinquishment as an answer because he’s in the TESCREAL movement — specifically, a camp of TESCREALism that hasn’t come full-circle with Joy and Kaczynski, unlike Yudkowsky and his followers. Amodei still holds the view that Yudkowsky and other folks in Existential Risk Studies once embraced: we should continue apace while being dutifully cautious about the possibility of bad outcomes. Yudkowsky’s view is much more pessimistic, and hence more in-line with Joy’s: unless we shut it all down right now and reallocate our resources to studying existential risks, AI scientists are going to kill everyone.

Here you can see the continuing influence of Joy’s 2000 article — and Kaczynski’s manifesto.

Zooming out even more, it’s worth noting that the TESCREAL movement has fractured into competing camps over the past 5 years or so, since the release of ChatGPT: (1) the doomers, (2) the accelerationists, and (3) those somewhere in the middle. Yudkowsky, of course, exemplifies (1), whereas Kurzweil and Amodei fall into category (3). Kurzweil, for example, argues that there might be up to a 50% chance of annihilation due to GNR technologies, but that the only way forward is through. Amodei has also acknowledged that the technology he’s building might result in an existential catastrophe (his p(doom) is at 10-25%).

The odd man out is (2), as they strongly disagree with Kaczynski, Joy, Yudkowsky, Kurzweil, and Amodei that there’s any significant risk at all. Rather, they believe the default outcome is utopia — annihilation isn’t really on the menu of options. Because of this, they constitute a new position that wasn’t present during the Joy-Kurzweil debate: rather than agreeing that there are serious risks but disagreeing about what the right response is, they simply reject the claim that there are any serious risks at all.

Examples of accelerationists in category (2) are Marc Andreessen and Gill Verdon, better known online as “Beff Jezos.”

Conclusion

I hope you found this article interesting and, hopefully, somewhat insightful. I’d love to know what you think I might be missing, or wrong about, in the comments. As always:

Thanks for reading and I’ll see you on the other side!

Incidentally, Kate and I recently recorded a podcast episode on this very topic, which you can listen to here.

I had a citation for this, but now can’t find it. Leave a comment if you think this is inaccurate. Thanks so much!

“Friendly AI” is now more commonly referred to as “controllable” or “value-aligned” AI.

My sense is that Yudkowsky’s view coinciding, more or less, with Joy’s happened in late 2022, after the release of ChatGPT. As alluded to elsewhere in this article, ChatGPT really freaked out a lot of people in the TESCREAL movement. It seemed like a leap — not a small step — toward ASI, and hence implied that the apocalypse may arrive much sooner than previously anticipated.

Incidentally, Kaczynski’s short essay “Ship of Fools” reminds me so much of Yudkowsky’s writing. It’s a fictional tale of a ship that’s heading into the Arctic. People on the ship bicker about social justice issues, which distract them from a lone voice screaming that none of that matters because everyone will soon be dead. That echoes, almost exactly, Yudkowsky’s remarks about how social justice is a non-issue given the imminent threat of ASI. See this section of a previous newsletter article for details. Honestly, “Ship of Fools” could very well have been written by Yudkowsky — it’s that close to Yudkowsky’s thinking and preferred way of communicating (through fictional stories).

Great read. Thank you.

Wouldn't you want to write about what the existential risk or more specifically AI safety research entails? I really can't imagine much if anything about it. Except doing thought experiments.

I already got one strike for reading one of their books aloud on YouTube without a disclaimer. Should I go 2 for 2?