The Growing Specter of Silicon Valley Pro-Extinctionism (Part 1)

The digital eugenicist Daniel Faggella argues that humanity should be replaced by a "worthy successor" in the form of AGI — his view is comically absurd and profoundly dangerous. (3,300 words)

That which optimizes to be kind will be vanquished by that which optimizes to not die. — Daniel FaggellaMeet Daniel Faggella, a pro-extinctionist who leads the so-called “worthy successor” movement, which hopes to create an advanced AGI system to replace humanity. He claims that “the great (and ultimately, only) moral aim of artificial general intelligence should be the creation of Worthy Successor,” which he defines as “a posthuman intelligence so capable and morally valuable that you would gladly prefer that it (not humanity) control the government, and determine the future path of life itself.” We can call this version of pro-extinctionism “digital eugenics.”

Earlier this year, Faggella held a “Worthy Successor: AI and the Future After Humankind” conference in a San Francisco mansion (where else?), which he claims was attended by “team members from OpenAI, Anthropic, DeepMind, and other AGI labs, along with AGI safety organization founders, and multiple AI unicorn founders.” This points to the appetite that Silicon Valley dwellers have for pro-extinctionism.1 According to a recent announcement, Faggella is planning another such conference later this month in New York City, which aims to place “diplomats, AGI lab employees, AI policy thinkers and others into one room to discuss the trajectory of posthuman life.”2

Here are a few tweets of Faggella from just the past few days (as of this writing), to give you a sense of his eschatological belief system:

Terminology

Faggella borrows some terms from Spinoza, who was not a pro-extinctionist, in making his argument: conatus is “the innate drive of all living things to persist, to survive.” Potentia refers to all the ways that conatus can be fulfilled — from photosynthesis to claws, shells, camouflage, the five senses, etc. (This is not, by the way, how Spinoza understood the term “potentia.”)

Faggella argues that all of ethics can be reduced to a single imperative based on a monistic theory of value: maximize potentia. Or, in his words, “a safe (or at least not overtly and unnecessarily dangerous) expansion of potentia is the sole moral imperative.” How can this be achieved? By building superintelligent AGI, or by merging tech into our brains (though Faggella says he agrees with Ray Kurzweil that artificial material will ultimately win: “The non-biological will almost certainly trump the biological in its importance”).

Two other terms of his are necessary to understand this view: the torch and the flame. The former refers to the substrate of the flame, while the latter doesn’t have a consistent definition in Faggella’s writing. Sometimes he defines it as “life itself,” while on other occasions he talks about the “flame of consciousness and potentia.” (Life is not the same as consciousness; some living things, like bacteria, aren’t conscious.)

The key idea is that the torch doesn’t matter — what’s important is the flame. And since humans are just one kind of torch that can carry the flame, we ultimately don’t matter and, as such, should be discarded in the future.

Five Objections

Where does one start with this? Here are five objections:

(1) Colonizing Space Will Awaken the Worst Nightmares of Catastrophic Warfare

Faggella likes to ask what the ultimate point or telos of technology is. As noted, he claims that it’s maximizing potentia such that “greater” (artificial) beings come into existence and then colonize the entire universe

with a fleet of vessels, traveling near light speed — converting planets into more vessel-making material, and converting stars into energy-providing hubs in ways that are outlandishly more powerful than any of the Kardashev Scale ideas that our silly little hominid brains could cook up.

He imagines that these future beings “can literally materialize spaceships, food, or other materials/things out of thin air with nanotechnologies or other advancements we don’t even understand,” and that they will have access to a “near-infinite range of blissful sentient experiences.” “Whenever it speaks,” he adds, “you get the impression that it knows a billion times more than you — as if a human were able to communicate with a cricket (but you’re the cricket).”

These are good examples of utopian thinking: wild, fantastical claims that conveniently ignore the messy details of what such a future would actually look like. For example, there are compelling arguments for why colonizing space would likely yield constant catastrophic wars between different planetary or solar civilizations.3 I wrote a paper on this several years ago (an accessible summary is here), and the world-renowned international relations theorist Daniel Deudney published a whole book about it in 2020 titled Dark Skies, which I highly recommend.4

The argument, very briefly put, is this: if future beings have the technology to spread beyond our solar system, they will probably also have the technology to inflict catastrophic harm on each others’ civilizations. There may be cosmic weapons we can’t even imagine. Furthermore, outer space will be politically anarchic, meaning that there’s no central Leviathan (or state) to keep the peace. Indeed, since a Leviathan requires timely coordination to be effective, and since outer space is so vast, establishing a Leviathan will be impossible. (In other words, there will be no single civilization, but a vast array of these civilizations, populated by beings with wildly different cognitive capabilities, emotional repertoires, technological capacities, scientific theories, political organizations, and even religious ideologies — etc. etc.)

This leaves the threat of mutually assured destruction, or MAD, as the only mechanism for securing peace. But given the unfathomably large number of civilizations that would exist (because the universe is huge), it would be virtually impossible to keep tabs on all potential attackers and enemies. Civilizations would find themselves in a radically multi-polar Hobbesian trap, whereby even peaceful civilizations would have an incentive to preemptively strike others. Everyone would live in constant fear of annihilation, and the inherent security dilemmas of this situation would trigger spirals of militarization that would only further destabilize relations in the anarchic realm of the cosmopolitical arena.

This is a recipe for nightmares to come true — on a cosmic scale. And it might be exacerbated by Faggella’s own suggestion that the AGIs that colonize the universe from the starting-point of Earth would simply try to annihilate other lifeforms that it might encounter:

As this great AI blasts through the galaxy, it eventually faces other alien intelligences. Do you suspect, reader, that all those alien intelligences will happily meet and greet our tender and caring AGI? Will they gladly share the energy of stars, or the resources of asteroids?

That which optimizes to be kind will be vanquished by that which optimizes to not die.

And so, it’s war.

(2) More Technology Means More (Rather than Less) Risk

Faggella argues that more advanced technology — including AGI, after which the AGI would take over the development of even more advanced tech — is the only way to ensure the long-term survival of the flame. He writes:

There is no eternal post-scarcity, and there is no perfect equality. Survival is always precarious. If not from predators with claws, from solar flares. If not from solar flares, then from running out of resources. If not from running out of resources, from the heat death of the universe, and on and on.

The problem with this view is the obvious: before the 20th century, the probability of an “existential catastrophe” was absolutely minuscule, because global-scale catastrophes are extremely rare. With the development of tech since the 20th century, people like Nick Bostrom and Toby Ord argue that the probability skyrocketed from negligible to between 25% and 16%. Some, like Eliezer Yudkowsky, argue that it’s now greater than 95%. And it’s not just TESCREALists saying this: the Doomsday Clock is currently set to 89 seconds before midnight, or doom. If there had been a Doomsday Clock 150 years ago, it would have been set to something like ~24 hours before doom — that’s how low the risk of global catastrophe was prior to the 20th century!

Could the correlation (and its underlying causation) be any clearer: more technology equals more existential risk. That’s been true in the past, without exception, and will continue to be true in the future, whether it’s us or a “superintelligent” AGI building the technology. If you want to increase the risk of a global catastrophe, then you should join Faggella’s team. Expanding “potentia” is not the best way to ensure that the “flame” persists into the far future — it’s actually the worst.

As for “running out of resources,” I don’t understand why Faggella highlights this. We could always, you know, choose to live sustainably. This point is so obvious as to hardly be worth mentioning.

(3) An Endless Succession of Successors, Each More Alien than the Last

There would be no end to the process that Faggella advocates. He writes:

There is likely something beyond consciousness — kinds of meta-consciousness or connectedness or thinking or understanding — that we cannot possibly imagine as humans, but which will open up nature’s possibilities a billion-fold to the posthuman entity that unlocks them. … The vast majority of new kinds of mental, physical, social, etc. potentia are completely unimaginable to humans, just as the variety of human types of potentia are wholly unimaginable by crickets or horseshoe crabs. Our loftiest ideas are just fries on the pier.

Sure, but one could say this about every iteration of new “successor.” Meta-consciousness? What about meta-meta-consciousness? Or meta-meta-meta-meta-meta-consciousness?

If one takes Faggella seriously, then the sole task of each iterative generation of successors would be to immediately start creating the next generation of successors, ad infinitum. (This follows from his only moral imperative and monistic value theory: to maximize potentia, which he seems to think every future being ought to follow forever.5) Once we create a “worthy successor” in the form of AGI, that AGI must then immediately start designing its own “worthy successor” replacement, AGI+. Once AGI+ arrives, its immediate and sole task will be to design AGI++, and so on — because there will always be “new kinds of mental, physical, social, etc. potentia [that] are completely unimaginable” to any given generation of “worthy successor.”

When the heat death of the universe finally occurs, what will have been accomplished? Which generation of successor will have been able to say, “I stopped to smell the roses and paused to appreciate the world around me, because I was enough”? None of them. The process is aimlessly endless (and endlessly aimless) because there’s presumably no upper limit on “potentia.”

This ethos is precisely what’s made Elon Musk such a patently unhappy person: there’s always another $1 billion to add to his obscenely giant heap of wealth, so the work never ends, nor is there any point at which the work actually becomes “worth it.”

(4) Value for Us or Us for Value?

This leads to a philosophical point: Faggella has a profoundly off-putting view of ethics and value, though it’s basically the same as that found among totalist utilitarians.6 He identifies value with the “flame,”7 and creatures like us as the expendable/fungible “torches” that merely carry the flame. This is exactly the way that utilitarians think about people: we’re the expendable/fungible containers, vessels, or substrates of “value.” You and I have absolutely zero intrinsic value. We matter only insofar as we bring this thing called “value” into the universe. It’s a very capitalistic way of thinking about morality, which is why I’ve described the approach as “ethics as a branch of economics.”

One sees this in Faggella’s approach. Like the utilitarians, he gets things exactly reversed: we matter for the sake of value, on his view, rather than value mattering for the sake of us. This is precisely why he advocates eliminating humanity in the future by replacing us with AGIs. These AGIs, in turn, won’t matter anymore than we do, because they’ll also be mere expendable/fungible “torches” whose moral significance is entirely bound up with their capacity to carry the “flame.” In a phrase: Faggella claims to care about “life” and “consciousness” yet doesn’t care about any of the things that are alive and conscious.

This idea is at the very heart of his worldview. And it’s an incredibly alienating, soulless approach to ethics (and eschatology). It sees humanity — along with whatever AGI posthumans we create, and whatever post-posthumans they might create — as mere means to an end rather than ends in themselves. It doesn’t take seriously the claim that you and I matter in any moral sense, except as instruments or vehicles for something else (potentia, the expansion of the “flame”).

In contrast, my personal view is that you and I don’t matter for the sake of value; value matters for the sake of us. I actually care about the “torches” in Faggella’s phraseology, because, you know, I’m not a capitalist psychopath who only looks at other living creatures as expendable/fungible things with merely instrumental value.

Faggella claims to care about “life” and “consciousness” yet doesn't care about any of the things that are alive and conscious.Furthermore, underlying this broadly utilitarian approach is a very peculiar conception of the morally correct response to value (that is, to whatever it is that we take to be valuable). For folks like Faggella, the correct response is always and only maximization. He wants more more more of the “flame,” spread to every corner of the universe. But there’s a vast array of alternative responses to value such as cherishing, treasuring, loving, caring for, respecting, protecting, savoring, preserving, adoring, appreciating, and so on. I’m not opposed to sometimes maximizing value, but it’s profoundly wrongheaded (indeed, it’s insanity) to think that this is the only correct response to what’s valued.

I cherish an old gift from my grandmother, treasure the moments I have with friends, love and care for those in need, appreciate the verdant forest near my home and the midnight firmament full of stars above me, etc. I don’t think: “Ah, gifts from my grandmother — there should be as many of those as possible!” or “Because the forest near my home is beautiful, the entire Earth, including arid lands, deserts, etc., should be covered in forests. Oh, and the moon, too!” Valuing something doesn’t always mean wanting there to be the maximum number of instances of that thing in the world (or universe). In many cases, it doesn’t mean that at all.

When one takes this perspective, it becomes clear that the “never good enough” attitude associated with the sole imperative of maximization is morally bankrupt. Recall here that the top regrets people have on their death beds aren’t that they didn’t strive harder, earn more money, acquire more stuff, etc. — all of which our capitalist society tells us to maximize — but that they didn’t let themselves be happier, stay in touch with friends, and work less. Maximization is a recipe for death-bed regret; cherishing and savoring isn’t. What lessons does this have for grand visions of humanity’s future?

(Note that this idea is also directly relevant to the third point above — see, e.g., the reference to Musk, a guy who loves humanity but couldn’t care less about humans, in exactly the same way that Faggella cares about life but not living things.)

(5) The Only Plausible Option Is Involuntary Extinction

Perhaps the most egregious part of Faggella’s digital eugenics is that the only way it will ever be implemented is through involuntary means. There is no way that everyone around the world, or even a majority of people, will ever agree that we should replace ourselves with AGI. Because most people are sane. Hence, Faggella’s pro-extinctionist position is a complete nonstarter for the vast majority of humans. This means that if we are someday replaced by AGIs, it will not be with the consent of humanity.

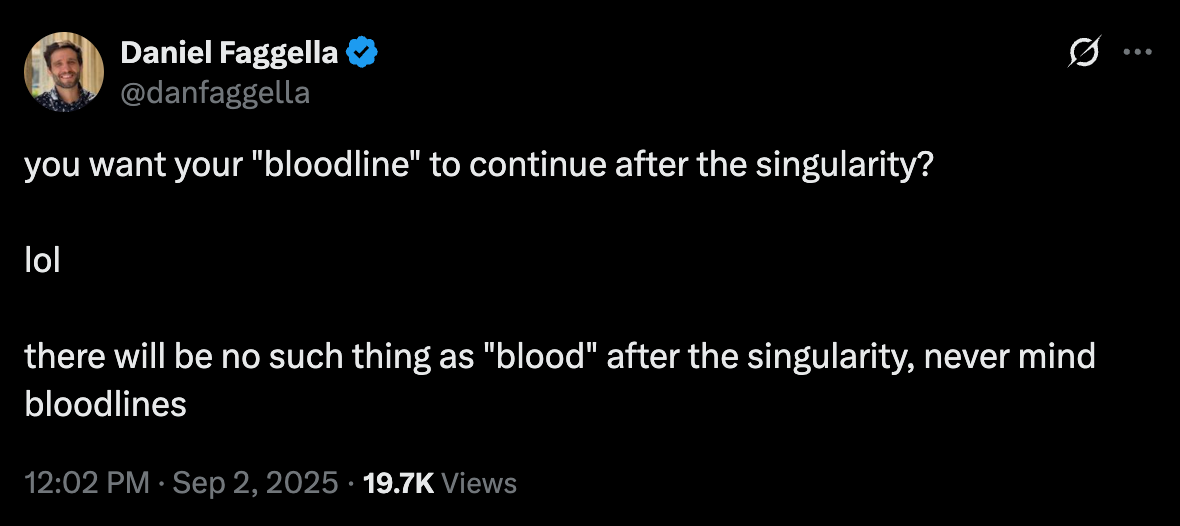

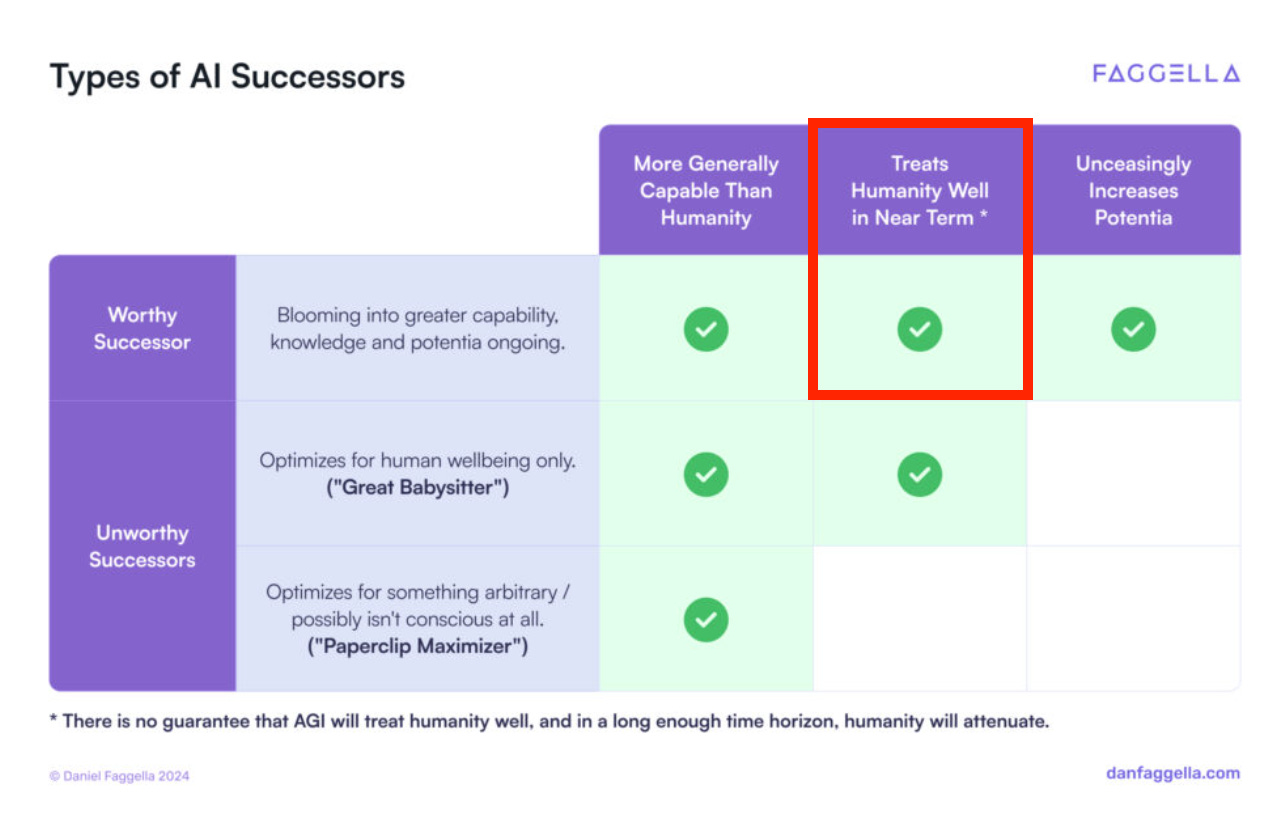

That leaves things like violence, coercion, mass murder, and the violation of human rights as the only plausible ways for AGI to usurp us — a fact that Faggella seems not to have thought much about. He does, however, reassure us that our “worthy successors” won’t do this right away. They’ll at least “treat humanity well in the near term” (paraphrasing the image below), though in the long-term we will be forcibly eliminated — but, Faggella tells us, not in a “reckless” manner. Umm, how, then will it get rid of us?

Another question: what’s to become of the natural world if AGIs take over? Do nonhuman organisms have any say about their fate? Faggella argues that AGIs should replace humanity because they’d be, as it were, bigger torches that can produce a larger flame. If that’s the case with us, then it’s even more so with nonhuman critters. Hence, the likely outcome of AGI taking over is the complete annihilation of the entire biosphere — all the majestic wonders of this exquisitely unique island in space, painted in greens and blues, bustling with ecosystems, and overflowing with exotic lifeforms, exterminated for the sake of climbing some poorly defined ladder of “potentia.”

Giving Up on the World

It’s hard to imagine a more impoverished, anti-human, and violent philosophy than what Faggella is peddling. I’m no Spinoza scholar, but I’m pretty confident that he’d be appalled by it — and by Faggella’s use of his terminology.8

The “worthy successor” movement basically instructs us to give up on this world by commanding us to create an entirely new world populated by wildly alien and inhuman beings — as Faggella writes: “(in the future) the highest locus of moral value and volition should be alien, inhuman.”9 It tells Silicon Valley dwellers exactly what they want to hear: “You’re not only excused from making this world a better place, but you’re a morally better person for channeling all your wealth and energy into building AGI instead.” Maximization, expansion, and ever-more technology — these are the things that will save the world, Faggella preaches, when in fact they’re exactly why we now face a polycrisis that threatens to precipitate the collapse of civilization in the coming decades. Claiming that more technology will make everything better, which is what Valley dwellers like to hear, is like saying that if you smoke a little more your cancer will go away.

The “worthy successor” movement is run by digital eugenicists who, so far as I can tell, are incapable of appreciating everything we have right now on, as it were, Planet A, our spaceship Earth. Reflect hard on the colorful mosaic of human cultures, peoples, nations, traditions, and ways of life; think of the immense diversity of living beings on this beautiful oasis in space, many of which possess kinds of intelligence that we’re only now beginning to understand. Contra Faggella and his followers in Silicon Valley, I encourage people to cherish, treasure, protect, and care for these profoundly valuable things, and to reject the narrow-minded, morally impoverished notion that more “potentia” and a bigger “flame” is what we should aim for.

Here I’m reminded of Holden Karnofsky’s confession that Effective Altruism (EA) “is about maximizing a property of the world that we’re conceptually confused about, can’t reliably define or measure, and have massive disagreements about even within EA.” This was meant to be a warning about maximization. The same point applies to “potentia” — indeed, perhaps much more to “potentia” than EA’s notion of “value.”Naomi Klein had a lovely response to a question on Democracy Now about how to counter the growing influence of techno-eschatological fanaticism in Silicon Valley (see time 19:58). Her solution to the problem: an affirmation of life, a belief in our world, because “we’re up against people who are actively betting against the future.” I agree. What Faggella presents, in every important respect, is a vehement rejection of our world and a rejection of Earthly life, in all its magnificent glory. If he were to get his way, everything that makes life worthwhile would be destroyed.10

Thanks for reading and I’ll see you on the other side!

If you like this content, you might enjoy my podcast with the comedian Kate Willett, Dystopia Now. Here’s our latest episode on AI girlfriends and AI slop (it’s genuinely quite amusing!): https://www.patreon.com/posts/my-bf-is-ai-137596479

Faggella also hosts a podcast called “The Trajectory.” It was on this podcast that Eliezer Yudkowsky said this:

If sacrificing all of humanity were the only way, and a reliable way, to get … god-like things out there — superintelligences who still care about each other, who are still aware of the world and having fun — I would ultimately make that trade-off.

As I write about Yudkowsky’s pro-extinctionist affirmation here:

He adds that this isn’t “the trade-off we are faced with” right now, yet he’s explicit that if there were some way of creating superintelligent AIs that “care about each other” and are “having fun,” he would be willing to “sacrifice” the human species to make this utopian dream a reality.

For reasons noted just below, there almost certainly won’t be any galactic civilizations, due to the vastitude of space.

My article, in fact, drew heavily from Deudney’s book, which I read prior to its publication.

Talking about locking in human values!

Here’s what Faggella writes about utilitarianism:

Purely utilitarian ethics: A utilitarian may advocate for posthuman entities or worthy successors, but they presume that one specific human-conceivable kind of value (positive or negative qualia) is and will always be the singular measure of moral value. Utilitarianism is anthropocentric in the fact that it embodies the hubris of believing that homo sapiens have discerned all possible value and discovered the one greatest and highest value. AC thinkers [where “AC” stands for “axiological cosmism,” which is Faggella’s view] believe that great magazines of powers, experience, and value exist wholly beyond human conception, and could only be explored (nevermind optimized for) by vastly posthuman beings.

This is not accurate: one can be a utilitarian and also hold that we don’t actually know what “value” is. Faggella’s rejection of utilitarianism, his view is very utilitarian: there is one correct response to value (maximization), and the only thing that’s intrinsically valuable is the “flame” (consciousness, life, or whatever — a form of monism, like hedonism and desire-satisfactionism). My approach to value theory, in contrast, is far more pluralistic, as monism tends to be quite unsophisticated.

Though he’s sometimes unclear about this.

It’s an even more appalling version of pro-extinctionism than that advocated by the Gaia Liberation Front, since even they want nonhuman organisms to persist. Faggella’s view is closer to Efilism, which aims to snuff out all life in the universe — the only difference is that Faggella wants a very particular kind of AGIs to do this snuffing out, after which they will immediately start building AGI+, which will immediately build AGI++, etc. until the universe is full of all sorts of alien beings engaged in constant war (because, again, the cosmopolitical realm is anarchic).

Italics added.

Thanks to Remmelt Ellen and Ewan Morrison for helpful comments on a draft of this article.

This guy. 🙄 I wonder if he’s read CiXin Liu’s Remembrance of Earth’s Past trilogy (3 Body Problem). Liu tackles the moral issues of what happens to humans disconnected from Earth and it’s not good. These Silicon Valley guys are so misanthropic and disconnected from reality…it really is a special kind of psychopathy.

"This is a recipe for nightmares to come true — on a cosmic scale. And it might be exacerbated by Faggella’s own suggestion that the AGIs that colonize the universe from the starting-point of Earth would simply try to annihilate other lifeforms that it might encounter:" Ian Douglas wrote a series of books about this idea. He called them "The Hunters of the Dawn" and they were a post-biological race that killed any other species that figured out FTL travel. The last book came out in 2009. I haven't thought about it in years until I read this.