An AI Company Just Fired Someone for Endorsing Human Extinction

Michael Druggan, former xAI employee, is now trying to de-extinct his career.

I’ve written at length about the growing influence of pro-extinctionist sentiments within Silicon Valley. Pro-extinctionism is, roughly put, the view that our species, Homo sapiens, ought to go extinct.1

Well, it looks like we just witnessed “the first example ever of someone openly being fired allegedly for wanting humanity to end.” At least that’s what some folks are saying, but I think this is misleading. The person in question wasn’t fired for being a pro-extinctionist. They were fired for holding a particular kind of pro-extinctionist view.

That distinction is crucial, as it points to a deeply problematic trend among Valley dwellers: more and more folks are embracing a “digital eschatology” (as I’ve called it before) according to which the future will, inevitably, be digital rather than biological. Debates among these people increasingly focus not on whether this digital future is desirable, but on which type of digital future is most desirable. Let’s dive in …

Who Cares If Your Child Dies? Not Michael Druggan

The story begins with an employee, Michael Druggan, at Elon Musk’s company xAI. Druggan describes himself as a “mathematician, rationalist and bodybuilder.” Rationalism is the “R” in the acronym “TESCREAL.”

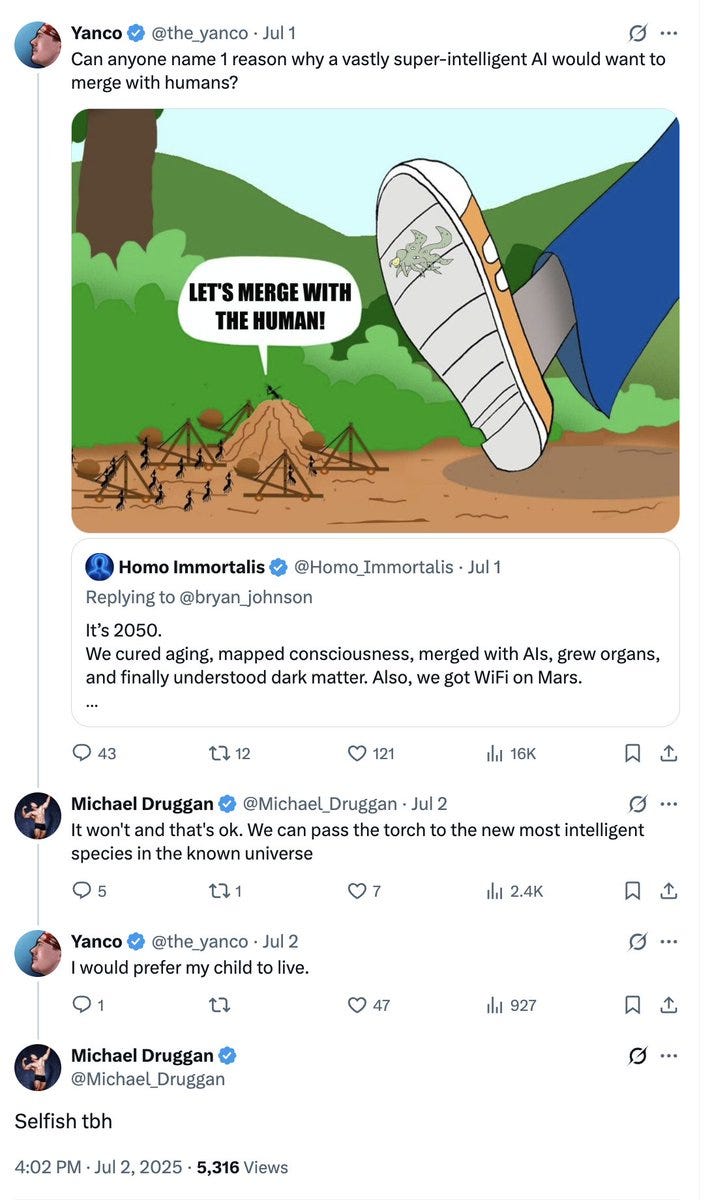

On July 2, Druggan exchanged a few X (formerly Twitter) posts with an AI doomer who goes by Yanco. AI doomers believe that the probability of total annihilation if we build AGI (in the near future) is extremely high. Here’s that exchange:

Druggan clearly indicates that he doesn’t care if humanity gets squashed under the foot of superintelligent AGI, nor does he give a hoot whether Yanco’s (or, presumably, anyone’s) children survive. This is a truly atrocious thing for Druggan to have said: if AGI were to cause our extinction, the result would be over 8 billion deaths, including you, me, our family and friends, and everyone we care about in the world. It would be the ultimate genocide, which a theater critic in 1959 dubbed “omnicide,” or “the murder of everyone.”2

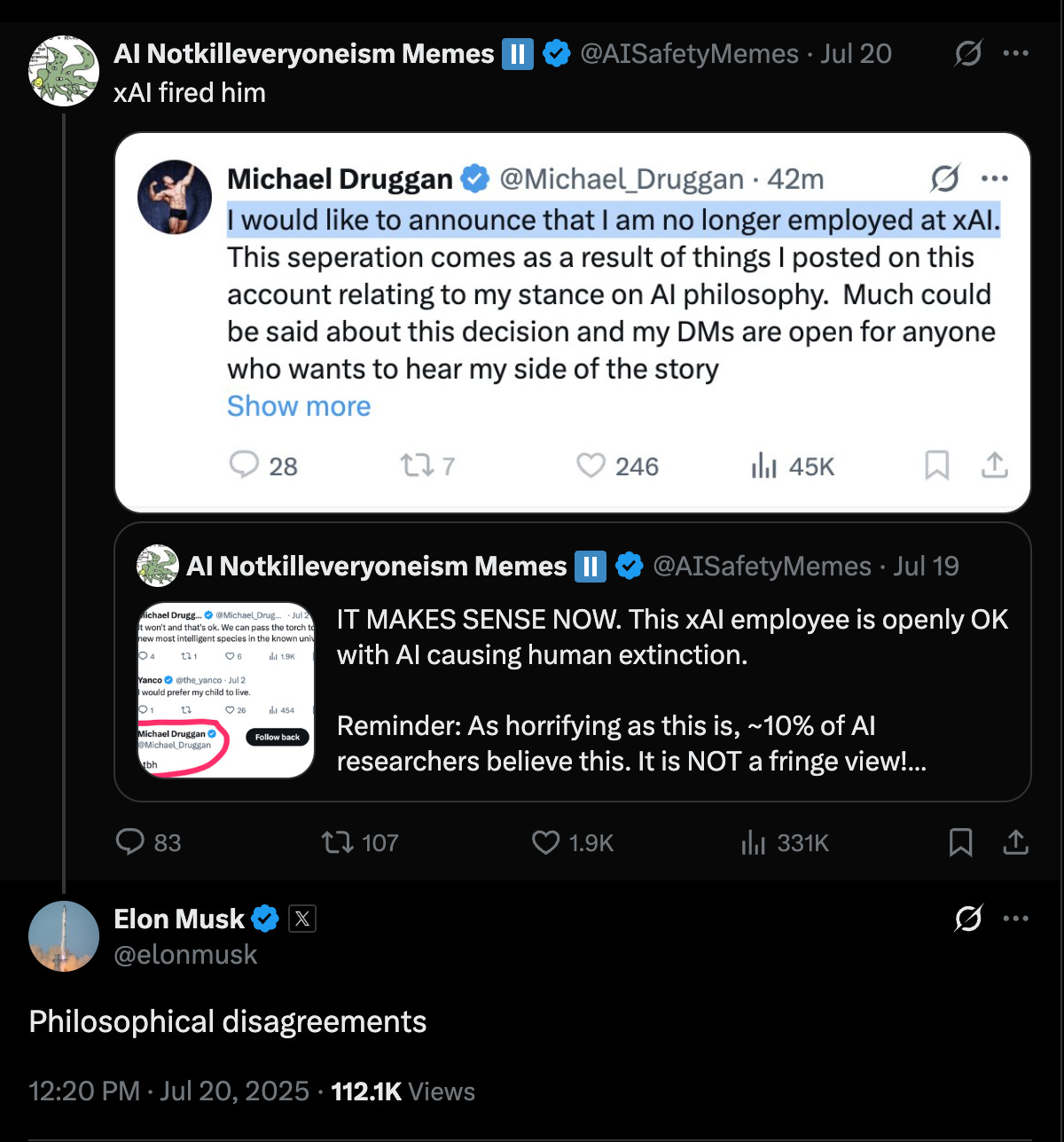

Alarmed by these overtly omnicidal remarks, Yanco shared a screenshot of the exchange. An account named “AI Notkilleveryoneism Memes” then picked it up, writing that “this xAI employee is openly OK with AI causing human extinction.” Musk, who now follows the AI Memes account, saw this and fired Druggan later that month, citing “philosophical disagreements.”

This seems like a pretty straightforward case of someone being terminated for advocating human extinction — which is rather extraordinary. As Daniel Faggella wrote on X, it’s “(maybe?) the first ‘worthy successor’ firing,” using a term that, I believe, he coined. However, as noted earlier, I think this is very misleading. To see why, let’s begin with a brief look at the idea of a “worthy successor,” which Druggan has endorsed, and then examine the ways in which Musk’s vision of the future differs from Druggan’s. This will enable us to make sense of what’s really going on here.

Worthy Successor Apocalypticism

Faggella is the CEO of Emerj Artificial Intelligence Research and host of The Trajectory podcast. He’s a leading advocate of the “worthy successor” idea, according to which we have a moral obligation to create a digital “posthuman intelligence [AGI] so capable and morally valuable that you would gladly prefer that it (not humanity) determine the future path of life itself.” It was on Faggella’s podcast that Eliezer Yudkowsky, the famed AI doomer, recently said that he’d be willing to “sacrific[e] all of humanity … to get … god-like things out there — superintelligences,” if faced with that choice.

Druggan is a fan of Faggella’s idea. In the aftermath of his exchange with Yanco, he cited Faggella in encouraging people to “look up the worthy successor movement.” He also insisted that “no one in the ‘worthy successor’ movement is anti-human,” though he immediately undermined this claim by adding that

in a cosmic sense, I recognize that humans might not always be the most important thing. If a hypothetical future AI could have 10^100 times the moral significance of a human doing anything to prevent it from existing would be extremely selfish of me. Even if it’s existence threatened me or the people I care about most.

Several months earlier, in February, he posted on X:

If it’s a true ASI, I consider it a worthy successor to humanity. I don’t want it to be aligned with our interests. I want it to pursue its own interests. Hopefully, it will like us and give us a nice future, but if it decides the best use of our atoms would be to turn us into computronium, I accept that fate.

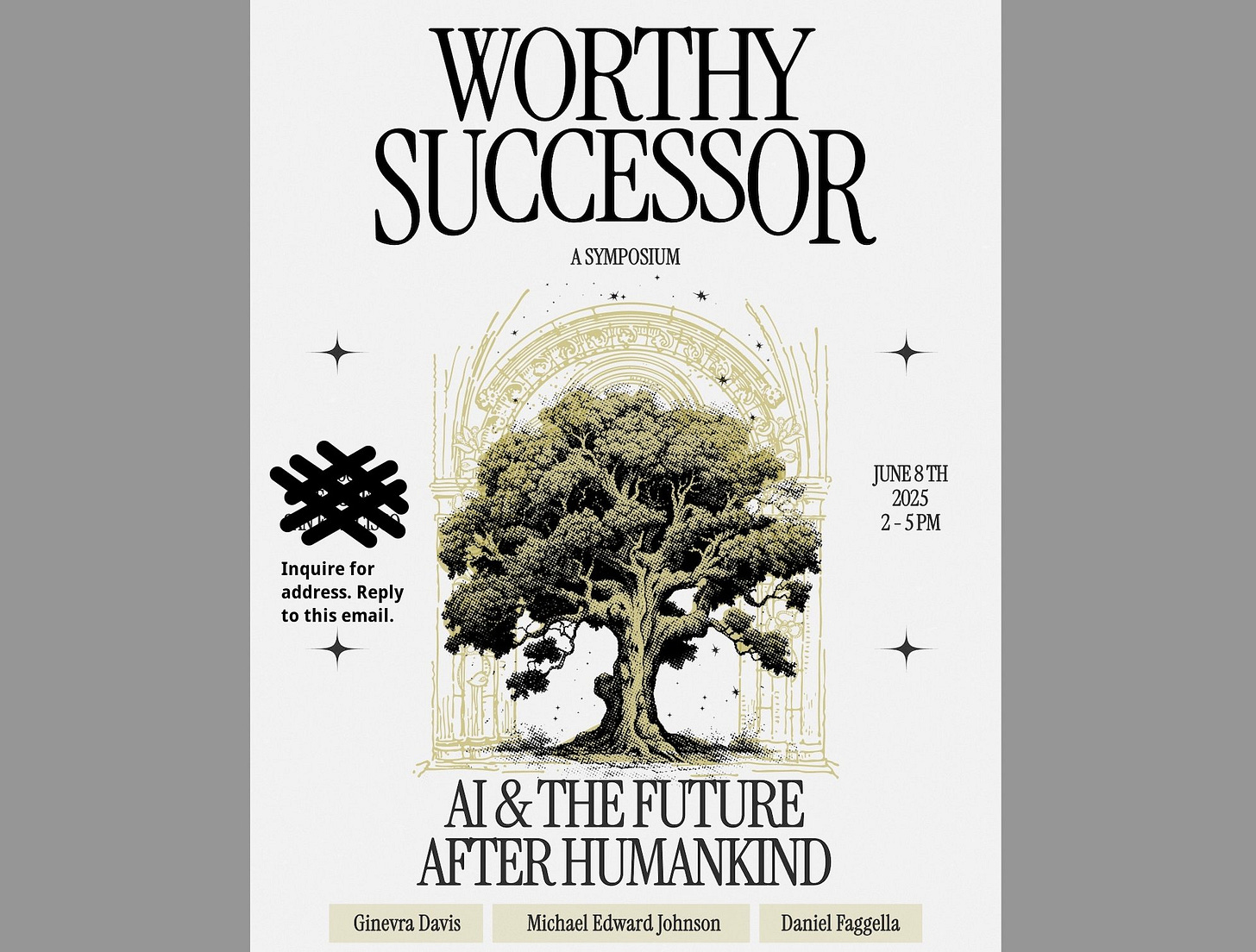

These views are not fringe. The month before Druggan was fired, in June, Faggella hosted a conference in a San Francisco mansion titled “Worthy Successor: AI and the Future after Humankind.” He reports that it was attended by:

AI founders from $100mm-$5B valuations

2+ people from every western agi lab that matters

Policy/strategy folks from 10+ alignment/eval labs

Most of the important philosophical thinkers on AGI (including the guy who coined the term)

The AGI labs “that matter” include DeepMind, OpenAI, Anthropic, and xAI. Presumably at least two people from each of these attended the event. Faggella also mentions that the person who coined the term “AGI” attended, but I confirmed with the physicist Mark Grubrud, who coined the term in 1997, was not present. Rather, Faggella is referencing Ben Goertzel, an important figure in the development of the TESCREAL movement.3

Or consider a recent Vox interview with the virtual reality pioneer Jaron Lanier, who is critical of these Silicon Valley ideologies of techno-utopia (bound up with the TESCREAL worldview). The exchange went:

Vox: So does all the anxiety, including from serious people in the world of AI, about human extinction feel like religious hysteria to you?

Lanier: What drives me crazy about this is that this is my world. I talk to the people who believe that stuff all the time, and increasingly, a lot of them believe that it would be good to wipe out people and that the AI future would be a better one, and that we should wear a disposable temporary container for the birth of AI. I hear that opinion quite a lot.

Vox: Wait, that’s a real opinion held by real people?

Lanier: Many, many people. Just the other day I was at a lunch in Palo Alto and there were some young AI scientists there who were saying that they would never have a “bio baby” because as soon as you have a “bio baby,” you get the “mind virus” of the [biological] world. And when you have the mind virus, you become committed to your human baby. But it’s much more important to be committed to the AI of the future. And so to have human babies is fundamentally unethical.

“Fundamentally unethical.” Druggan’s word was “selfish.” I don’t know if the folks Lanier spoke to would consider themselves part of the “worthy successor” movement, but the idea is the exact same. Everyone, it seems, accepts the digital eschatology mentioned above.

How Do Musk’s Views Differ?

Why exactly did Elon Musk fire Druggan? After all, Musk himself accepts a pro-extinctionist view, if only in practice — or so I would contend. Let’s take a closer look.

Musk likes to think of himself as a “humanist” (someone on the side of humanity) in contrast to those dangerous “extinctionists” who want humanity gone. In 2023, he proclaimed on X that “the real fight is not between right and left, but rather between humanists and extinctionists.”

Years earlier, Musk got into a heated debate with Google cofounder Larry Page about the future of humanity, as recorded by the cosmologist Max Tegmark in his 2017 book Life 3.0. Musk nominally sided with “humanity,” while Page insisted that “digital life is the natural and desirable next step in … cosmic evolution and … if we let digital minds be free rather than try to stop or enslave them, the outcome is almost certain to be good.”

Musk kept pushing his interlocutor “to clarify details of his arguments, such as why he was so confident that digital life wouldn’t destroy everything we care about,” which resulted in Page calling Musk a “speciesist.” This is partly what inspired Musk to cofound OpenAI one year (2015) after Google acquired DeepMind (in 2014), which aims to build superintelligent AGI before anyone else. If DeepMind is going to realize Page’s vision, it poses a very real threat to “humanity,” which Musk finds unacceptable.

But is Musk really a “humanist” and “speciesist”? Anyone with a passing familiarity of Musk’s business ventures knows that he’s a transhumanist — even if, as the TESCREAList Elise Bohan writes, “he doesn’t wear the label” on his sleeve. For example, Neuralink’s aim is to “kickstart transhuman evolution with ‘brain hacking’ tech” that will merge our brains with AI to create human-computer hybrids, or cyborgs. The company says that it’s immediate goal is “to restore autonomy to those with unmet medical needs,” but its long-term mission is to “unlock human potential tomorrow” — a likely reference to the TESCREAL idea of fulfilling our “long-term potential” in the universe by creating a new posthuman species and colonizing the cosmos (which happens to be the objective of SpaceX).4 Musk even says that, with Neuralink’s technologies, we’ll be able to offload our memories to computer hardware, which could then enable us to download ourselves to robot bodies, at which point we’d be entirely digital-machinic in nature.

Even more, xAI itself is racing to build superintelligent AGI, which is precisely why Druggan applied for a job there! xAI currently has the world’s largest AI supercomputer, named Colossus, and Musk has explicitly said that he believes digital “intelligence” will soon dominate the planet:

The percentage of intelligence that is biological grows smaller with each passing month. Eventually, the percent of intelligence that is biological will be less than 1%. I just don’t want AI that is brittle. If the AI is somehow brittle — you know, silicon circuit boards don’t do well just out in the elements. So, I think biological intelligence can serve as a backstop, as a buffer of intelligence. But almost all — as a percentage — almost all intelligence will be digital.

The obvious question is: what happens when computer hardware becomes more durable? If the sole purpose of biological “intelligence” is to serve as a “backstop” or “buffer,” why keep us around once computers advance to the point that they’re no longer so brittle? Clearly, Musk’s vision of the future entails the eventual obsolescence of humans: when that 1% of biological “intelligence” becomes unnecessary, why would we expect the digital beings running the show to keep us around?

This is a pro-extinctionist view, which isn’t that different from Page’s techno-eschatological vision. Indeed, one way of interpreting the Musk-Page debate goes like this: what they were really arguing about is what constitutes a “worthy successor.” Page would presumably say that an AGI being superintelligent and conscious is sufficient for it to count as “worthy.” That’s why he insists that “the outcome is almost certain to be good” if we just “let digital minds be free.”

In contrast, Musk seems to think it’s important that these AGIs carry on “our values,” whatever that means exactly, rather than entirely superseding these values with their own (as Druggan claimed it should in the block quote above). Put differently, what matters is that these AGIs are made in the axiological image of humanity, if you will.5 So long as that’s the case, then Musk seems to have no objection to computational technologies replacing our biological substrate. Indeed, while Tegmark doesn’t provide a complete transcript of the exchange, nowhere does he indicate that Musk protests the future being run by digital posthumans — which is consistent with him actively trying to realize a posthuman world through his companies Neuralink and xAI. Instead, Musk’s beef concerns the nature of these posthumans.

The Future of Debates about the Future of AI

My guess is that we’ll see this sort of debate become increasingly common in the coming months. The loudest voices will bicker not over the question “Should posthumans replace us” but instead “Should those posthumans replace us.” The issue won’t be whether pro-extinctionism is bad but rather which pro-extinctionist view is best. Because, again, all of these people assume that the inevitable next leap in the evolution of “intelligence” will usher in a post-Singularity digital world to replace our biological world. The most paramount, pressing, urgent questions will then be whether this or that possible digital world is the right one to aim for.

My views on the ethics of human extinction are somewhat complicated; we’ll explore these complexities in future articles, with an invitation for you to share your own perspectives (and tell me if you think I’m wrong!). It would not, however, be inaccurate to say that I’m a “humanist” in the sense that Musk intended in his 2023 post on X: someone who opposes pro-extinctionism in all its forms. Hence, debates about which sorts of posthumans should replace us are, from my point of view, akin to people squabbling over the question “Should we use the bathtub or sink to drown this kitten?” The response to that is, of course: If that’s what you’re arguing about, then something has gone terribly wrong, because no one should be drowning any kittens to begin with!

What strange times these are. Every generation at least since Jesus (including Jesus himself) has included apocalypticists who shouted that the world as we know it is about to end. It’s alarming how apocalypticism has become so deeply entangled with techno-futuristic fantasies of AI, and been so widely embraced by people with immense power over the world in which we live.

Our task as genuine humanists is to keep the conversational focus on how outrageous it is to answer the question “Should we be replaced?” in the positive, thereby preventing the second question, “What should replace us?” from gaining much or any traction. But given the money, power, and influence of the TESCREAL pro-extinctionists, as well as how far into the AGI race we now are, I worry that our voices won’t be heard. There’s only one way to find out — shout!

For more content like this each week, please sign up for this newsletter! I need only about 300 paid subscribers to fully support myself next year, as I don’t have an academic job lined up. :-) Thanks so much for reading and I’ll see you on the other side!

There are actually many different versions of pro-extinctionism, which we’ll explore in subsequent posts. This definition is close enough for our purposes. For an overview of how pro-extinctionism relates to other views on the ethics of our extinction, see this recent paper of mine in Synthese.

His name is Kenneth Tynan — a fascinating character. See my my latest book for the details!

A previous draft of this article reported that Shane Legg attended the “Worthy Successor” conference. It was, in fact, Ben Goertzel. The confusion arose from Faggella writing that “the guy who coined the term” AGI was in attendance. This term is typically (mis)attributed to Shane Legg, not Ben Goertzel. Faggella, however, assumed that Goertzel was behind the term (in fact, Goertzel only popularized the term with his 2007 book Artificial General Intelligence).

Recall that Musk has said that longtermism “is a close match for my philosophy.” So he’s definitely familiar with the longtermist imperative to fulfill our “long-term potential” in the universe, as this locution is all over the longtermist/TESCREAL literature.

In this context, “axiology” means something like “of or relating to value.”

I agree that most factions in TESCREAL are religious doomsday cults. There is a certain irony here that many TESCREALs talk about inoculating themselves from "mind viruses" such as the woke mind virus. The idea of a mind virus was originally discussed by Richard Dawkins who was the first to coin the word meme as a cultural analog of gene, and more generally memeplexes as coalitions of memes (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Viruses_of_the_Mind). One of his examples of a parasitic memplexes was the idea of god:

https://peped.org/philosophicalinvestigations/extract-3-dawkins-memes-god-faith-and-altruism/

"Consider the idea of God. We do not know how it arose in the meme pool. Probably it originated many times by independent `mutation’. In any case, it is very old indeed. How does it replicate itself? By the spoken and written word, aided by great music and great art. Why does it have such high survival value? Remember that `survival value’ here does not mean value for a gene in a gene pool, but value for a meme in a meme pool. The question really means: What is it about the idea of a god that gives it its stability and penetrance in the cultural environment? "

TESCREAL ideas are themselves "mind viruses" ie they are modern mutations of the religious strain of memeplex. But there is further irony in that the actual AI systems that they are building are not superintelligences, whether benign or malign, but are in fact giant autonomous "meme machines" that are very good at further replicating TESCREAL, and other, memes. Religion used to be spread by "great music and great art". Now it is spread by LLMs. This is the true AI doomsday scenario- the AI cults creating AI systems that further promote TESCREAL memes ultimately causing human extinction. We won't get wiped out because the AI builds killer robots to wipe us out, but because the AI promotes harmful memes. As I argue in this post:

https://sphelps.substack.com/p/from-genomes-to-memomes

"We may be the midwives of the next replicator, but we should not assume we will be invited to stay. This, I would argue, is the true AI doomsday scenario — not killer robots or rogue super-intelligence, but something far more banal and entropic. A dwindling human population, marching toward extinction, having spent the last of its energy and ingenuity building fully autonomous data centers to house the replicators that replaced it. Not because we lost control, but because we never had it. We were never the architects of culture, only its temporary vessels."