Humanity Won't Go Extinct This Century, But Civilization Will Probably Collapse

My sense is that most scholars who've seriously studied these topics would probably agree, though I don't know of anyone who's explicitly said this.

This article is unusually long (around 5,000 words). Most newsletter posts will be much shorter. Nonetheless, I hope you find my discussion below interesting. Thanks so much for reading and supporting my work!

In my recent book Human Extinction, I argue that the idea of human extinction dates back to Presocratic philosophers like Xenophanes and Empedocles, as well as to the ancient Greek atomists and Stoics. However, with the rise of Christianity in the 4th and 5th centuries CE, the very possibility of our species disappearing became more or less unthinkable to nearly everyone. The idea itself would have even seemed oxymoronic during this period, as Christians take the concept of humanity to contain within it the concept of immortality. (Each individual human is immortal, and hence humanity as a whole is also immortal.) To utter the sentence “Humanity can go extinct” would be tantamount to saying that an immortal thing can undergo something that only mortal things can undergo, which is an obvious contradiction.

Beyond this, Christians would have added that extinction, in a naturalistic sense, just isn’t the way our story ends — it’s not what God has planned for us. On this view of eschatology, the end is marked by transformation rather than termination.

With the decline of Christianity in the 19th century (when Friedrich Nietzsche famously declared that “God is dead”), conceptual space opened up for people to start thinking about the possibility of our extinction once again. Literary works like Lord Byron’s “Darkness” (1816) and Mary Shelley’s The Last Man (1826) exemplify this shift. The latter, for example, explores the trials and tribulations of Lionel Verney, the main character, as humanity dies out due to a global pandemic.

A few decades later, in the early 1850s, there was a sudden surge of new thinking (and freaking out) about our extinction after physicists discovered the second law of thermodynamics. Immediately, they realized the eschatological implications of this “terroristic nimbus” (to quote Josef Loschmidt, writing in 1876): Earth will someday become uninhabitable to humans, meaning that we’re fated to die out.

Another surge of extinction anxiety happened in early 1954, following the Castle Bravo nuclear test, which convinced most preeminent scientists that even a small-scale thermonuclear exchange between the US and Soviet Union could blanket the entire globe with life-destroying radioactive particles.1 This was followed by yet another spike of anxiety in the 1980s, due to scientists introducing the idea of a “nuclear winter” in 1983 (discussed below), along with the election of Ronald Reagan and the Soviet-Afghan War.

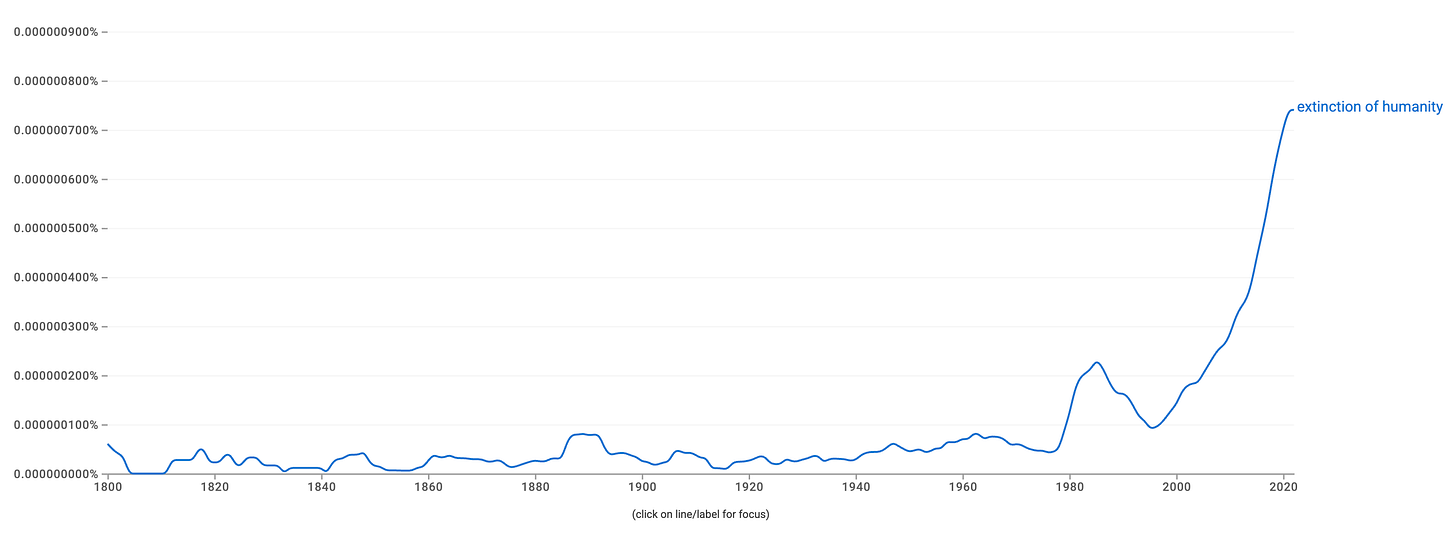

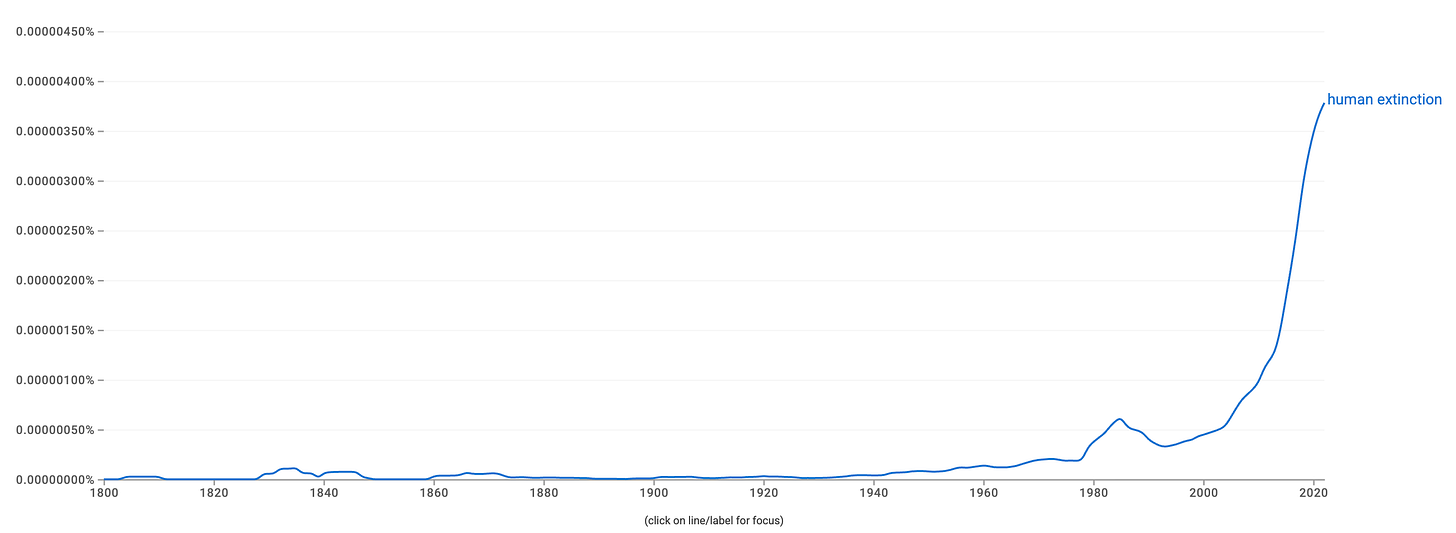

However, since the early 2000s, talk of human extinction has absolutely exploded. You can clearly see this in the Google Ngram Viewer results below, which track the frequency of terms like “human extinction” and “extinction of humanity” over time. The curve looks basically exponential, if not hyperbolic. Never before in human history — going all the way back to the ancient Greeks — has the topic of our extinction been more discussed and fretted over than it is right now. That makes the cultural-intellectual contours of our contemporary historical period genuinely unique!

Are We Next?

Given the recent explosion in thoughts about human extinction, the obvious question is: do the Google Ngram Viewer curves above correspond to an actual increase in the probability of human extinction actually happening? We know that over 99.9% of all species that have ever existed are now gone (Darwin himself drew this conclusion2), and that we’re in the early stages of the sixth major mass extinction event of the last 3.8 billion years. So, are we next? Will we, as some claim, be the first species to document its own extinction in realtime? Is the probability of our extinction this century exceptionally high? Is it growing? As Bertrand Russell once poignantly asked, is humanity writing the prologue or epilogue of its autobiography?

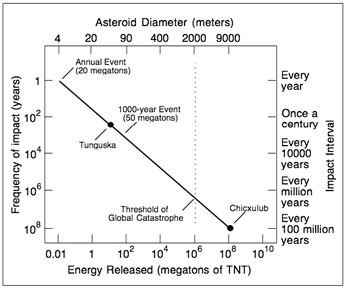

When I was in the TESCREAL movement (2009-2019), I felt quite confident that human extinction is highly probable this century.3 That’s precisely why I worked on “existential risks” — to bring this probability down. What nearly everyone agrees about is that prior to the 20th century, the likelihood of our extinction was extremely low, because humanity hadn’t yet invented powerful technologies like nuclear weapons that could annihilate everyone on Earth. The only notable risks to our survival were natural (or naturogenic, in contrast to anthropogenic), and global-scale natural catastrophes are highly improbable. For example, large asteroids capable of inducing a mass extinction happen only once every 100 million years. The Chicxulub impact, which killed off the non-avian dinosaurs 66 million years ago, can be seen in the bottom right of the graph below.

Volcanic supereruptions are far more probable, yet our species has a track record of surviving two such eruptions during the Pleistocene (here and here). One of these, however, was responsible for the Toba catastrophe that may have reduced the human population to only about 1,000 reproductive individuals some 75,000 years ago. Still, our ancestors found a way to push through!

Today, we face not just nuclear weapons, but the possibility of engineered pandemics involving designer pathogens, advanced AI systems that recursively self-improve to become “superintelligent,” and catastrophic climate change, among other threats. Surely, then, the probability must be much higher today than ever?

Nukes, Pandemics, and AI

I now think the probability is far lower than I once did. In fact, my considered opinion is that human extinction is extremely unlikely before 2100 — this is the good news, though I’ll share some rather dismal news about our collective predicament toward the end of this post!

Nukes

Consider first the threat of nuclear war. The greatest danger here isn’t the immediate impact of nuclear explosions — which, to be clear, could obliterate entire metropolitan areas, as you can see on Alex Wellerstein’s disturbingly fun NukeMap — but the resulting nuclear winter. When urban areas go up in flames, they can burn with such intensity that they generate firestorms, or massive conflagrations that produce their own gale-force winds. Bubbles of hot air then rapidly rise through the atmosphere and inject soot from the burning cities into the stratosphere, where there are no meteorological phenomena like storms to remove the soot. This means the only mechanism of removal is gravity, which operates on much longer timescales. Once in the stratosphere, the soot disperses around the globe, blocking out incoming solar radiation. Without sunlight, food chains collapse and people (along with many other animals) will starve to death in literally subfreezing temperatures under pitch-black skies at noon. Yikes!!

A noted study from 2022, published in Nature Food, concludes that “more than 5 billion could die from a war between the United States and Russia.” I contacted one of the study’s authors, and he told me that it’s within the realm of possibility that human extinction results from such a conflict, but that this is far from certain. What’s more likely is that a few billion people will survive in places like Australia and New Zealand, meaning that an all-out thermonuclear war probably wouldn’t be extinctional. A few billion people is a lot. Just consider that the “minimum viable population” for our species is estimated to be between 40,000 and a mere 150 individuals. If the former number is correct, this means that — as of this writing — a total of 8,243,407,897 people in total could die without human extinction happening, given that the current population is 8,243,447,897. As long as the survivors are geographically close enough to form a community and reproduce, our species would persist.

Since we’re specifically focusing on human extinction, whereby everyone on Earth perishes,4 nuclear war doesn’t look like a significant risk. It could very well result in the collapse of civilization, but we’ll get to that below!

Pandemics

Now consider global pandemics. The philosopher David Thorstad has an excellent series of articles on how the risks of a global pandemic have been exaggerated by existential risk researchers. It’s true that synthetic biology techniques like CRISPR-cas9 give us extraordinary power to edit the genomes of organisms, including pathogens, with immense precision. Within the laboratory of nature, there’s a basic tradeoff between the transmissibility of a pathogen and its lethality: if a virus or bacterium is too lethal, it will kill the host before it has a chance to infect someone else. Hence, the more lethal it is, the less transmissible. But technology would enable us to break this tradeoff. It’s theoretically possible to design a pathogen that’s as lethal as rabies but as contagious as the common cold, and if one further engineers it to have a long incubation period (like HIV, which takes 10+ years to become AIDS), then it could theoretically spread around the world unnoticed until nearly everyone is infected.

However, Thorstad offers a long list of reasons for thinking that this is highly unlikely. Someone harboring a death wish for humanity would need to get all the right laboratory equipment, successfully synthesize the pathogen without raising any red flags, figure out a way to disperse it in enough places (airports, subways, etc.) to initiate the process, hope that pathogen surveillance networks don’t detect it and, once detected, aren’t able to devise a cure once the infection becomes known, etc. Think about everything that would have to go “right” for this to kill every person on Earth — those living within uncontacted tribes in the Amazon, the tiny villages in northern Siberia, the outposts on Antarctica, and so on.

Eight-plus billion people is a lot of people, and as Thorstad observes, “human history is replete with examples of resilience not only to highly destructive pandemics, but also to the combination of pandemics with numerous other catastrophes.” Indeed, Europeans survived the 14th-century Black Death, a bubonic plague pandemic that killed up to 50% of the population — which is 50% away from 100%. To say that engineered pandemics could cause our extinction is to make an extraordinary claim, but there is no correspondingly extraordinary evidence to justify it.

Humans Are Incredibly Adaptable

Indeed, back in 2009, the futurist Bruce Tonn and Donald MacGregor co-edited a special issue of Futures in which contributors were tasked with devising plausible scenarios of total human extinction. One of the take-aways of this exercise was that it’s incredibly difficult to figure out how to eliminate the last few groups of people. As Tonn and MacGregor write:

At the beginning of the process of putting this special issue together, we, the two co-editors, were split on the likelihood of human extinction. MacGregor thought the probability was low and Tonn thought the probability was very high. At the conclusion of this process, Tonn has revised his probability radically downward.

Tonn subsequently reports in his solo contribution to the special issue that

it is the opinion of the author that the probability of human extinction is probably fairly low, maybe one chance in tens of millions to tens of billions, given humans’ abilities to adapt and survive.

Ten years ago, during my TESCREAL phase, I would have vociferously rejected Tonn’s assessment, as I agreed with existential risk researchers like Nick Bostrom and Toby Ord that the probability of our extinction is quite high this century. Bostrom claims that there’s at least a 20% chance of extinction, while Ord estimates a 1-in-6 probability: the odds of Russian roulette.

What do they base these numbers on? Not much. They’re basically pulled out of a hat, and just so happen to be exactly the sort of numbers one would promote if trying to convince funders to support existential risk research. In other words, you wouldn’t want a probability so high — e.g., 95% — as to make funding this research look otiose, but you also wouldn’t want a probability so low — e.g., Tonn’s estimate, which I now think is correct — as to make it look pointless for the opposite reason: there’s no real danger. Twenty percent and 16% are the sweet spots, and that’s why I think Bostrom and Ord chose them (even if they weren’t consciously aware of this).

In his excellent book More Everything Forever, Adam Becker asked Ord about his estimates of doom from AGI and “other imagined existential threats.” Becker writes:

Given the thinness of the evidence for an impending AI apocalypse, how can Ord be sure of the odds he’s assigning to it? He’s not. “I think a bunch of this comes down to what happens when you don’t know, what happens when there’s disagreement or uncertainty, ” he tells me. As for his estimate of the risk from unaligned AGI and other imagined existential threats, Ord says that he’s not trying to be strict or prescriptive about it. When it comes to his one-in-six estimate of extinction or collapse in the next century, he says, “it’s more of attempting to communicate Toby Ord’s credences about this probability, rather than trying to say, ‘Here’s a credence that you should have. And that if you don’t have it, and if you don’t get it, then you’re making an error. ’ It’s not meant to be that.”

So, there’s nothing rigorous about Ord’s estimates. In contrast, Tonn’s estimate looks — to my eye — far more reasonable because it isn’t an extraordinary claim that requires extraordinary evidence to take seriously. Humans are incredibly adaptable: we’ve survived two volcanic supereruptions, global pandemics like the Black Death and the 1918 Spanish flu, a couple of world wars, and even the radical environmental shifts that happened between the Pleistocene and Holocene. There are so many of us, living in so many remote regions, within self-sustaining communities, etc. that killing off the whole human population would be profoundly difficult. This brings us to AGI.

Artificial General Intelligence

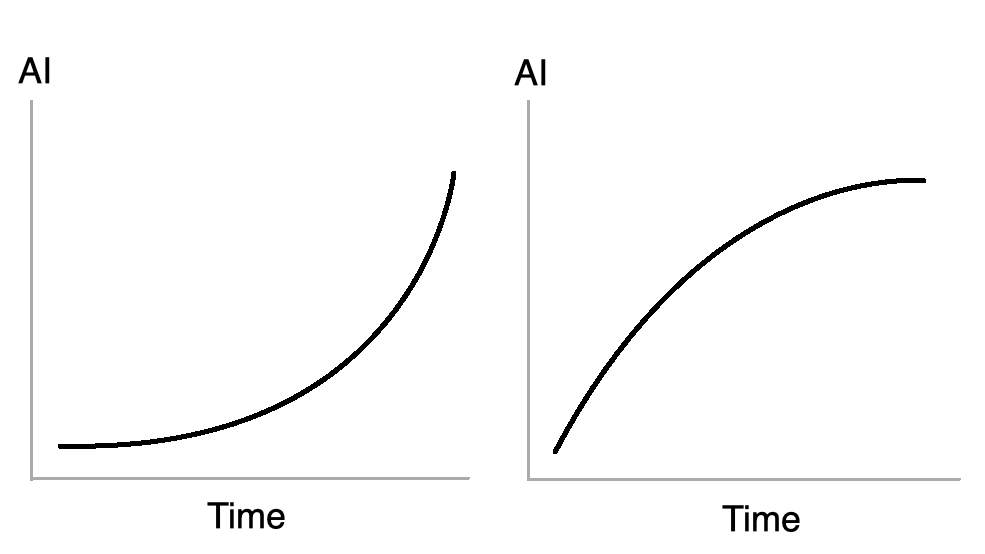

In a previous article for this newsletter, I explained why I’m not particularly worried about AGI annihilating humanity. A central thrust of that argument is that we’re nowhere close to building AGI, as the large language models (LLMs) that power current AI models are hitting a wall. Here I agree with the cognitive scientist Gary Marcus, who contends that we’d need an entirely new paradigm to reach the AGI finish line — perhaps something like neurosymbolic AI, which combines connectionist systems (e.g., LLMs) with more traditional “symbolic” computation (see GOFAI). We don’t need to get lost in the details here — suffice it to say that, since the probability of AGI is very low in the future, the probability of AGI killing everyone is correspondingly small.

That doesn’t mean, however, that I don’t think AI poses any “existential threats” (which are not the same as “existential risks”) to humanity, a point I’ll elaborate below. Nor does it mean that I think AGI — whatever that is exactly, as no one can agree on the definition — couldn’t potentially cause our extinction. I claimed above that killing off everyone on Earth would be extremely hard, but it seems to me that a genuinely “superintelligent” AGI (by which I mean a system that can outmaneuver us in every important respect, that’s better at solving complex problems, that can process information faster than human brains and institutions, etc.) could potentially find ways to exterminate the entire human population — perhaps by destroying the biosphere upon which our survival depends. After all, we have destroyed “less intelligent” (in the parenthetical sense specified above) species like the passenger pigeon and Mauritian dodo. I am very uncertain about this, though, so my views might change in the future.

The key point is that scaling up current LLMs aren’t going to result in AGI, which means that, based on our current best evidence, there’s no good reason to expect human extinction from AGI within the foreseeable future.

The Overall Risk Appears To Be Low

I focused above on the three biggest risks to our survival this century: nuclear war, engineered pandemics, and AGI, concluding that none are likely to precipitate our extinction. Someone somewhere will probably survive a nuclear winter and global pandemic, and claims of imminent extinction due to AGI are unfounded. This leads me to surmise that the probability of extinction isn’t much higher this century than it was prior to the 20th century.

Even more, there are some naturogenic risks that technology has effectively eliminated, thus rendering these already improbable events even more so. NASA’s “Near-Earth Object Program,” for example, leads “efforts to detect, track and characterize potentially hazardous asteroids and comets that could approach the Earth,” and “NASA estimates that over 90% of all the near-Earth objects larger than 1 kilometer have already been discovered.” (Recall, again, that the asteroid that killed off the dinosaurs was a whopping 10-12km in diameter.) If a large object were discovered to be on a collision course with us, it wouldn’t be difficult to launch a spacecraft to redirect it away from our orbit. This is exactly what inspired the recent “Double Asteroid Redirection Test,” which smashed a spacecraft into the moon of a minor planet to measure its impact — and it succeeded even more than scientists anticipated.

One threat we didn’t discuss above is climate change — because there’s a near-consensus among climatologists that it almost certainly won’t cause our extinction. It could, however, catalyze the collapse of civilization, which is what we turn to now.

Civilizational Collapse

In his 2003 book Our Final Hour, Lord Martin Rees writes: “I think the odds are no better than fifty-fifty that our present civilisation on Earth will survive to the end of the present century.” My personal view is that this is wildly optimistic. Although the probability of extinction is quite low, the likelihood of collapse seems to be extremely high. (To be clear, extinction would entail collapse, but not vice versa!) There’s no way I can provide an exhaustive explanation of my position in this post, but I’ll try to give you a sense of why I think this — do you believe I’m right? What am I missing?

Nukes (Again)

First, the probability of a nuclear conflict appears to have grown in recent years, thanks to Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. This is one reason the venerable Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists set the Doomsday Clock to a mere 89 seconds before midnight, or doom earlier this year— the closest it’s ever been since the Bulletin created it in 1948. Furthermore, even if the probability of a nuclear strike any particular year is low, this probability accumulates over time. As Martin Hellman, who founded nuclearrisk.org, observes, if the probability of a nuclear bomb being detonated is 1% each year, then “in 10 years the likelihood is almost 10 percent, and in 50 years 40 percent if there is no substantial change.”

I’d be somewhat surprised if I never witness a nuclear conflict in my lifetime, especially given the long list of nuclear “near misses” since the 1950s. Indeed, what worries me the most about the war in Ukraine isn’t Vladimir Putin intentionally using a nuclear weapon, but there being some unfortunate chain of events that leads to a nuclear mishap that spirals out of control. For all we know, there might have already been one or more nuclear near misses, but we’ll have to wait a few decades for this to become public knowledge.

If a nuclear conflict were to break out and kill 5 billion people, it’s very difficult to see how our modern global civilization would endure. The economic, agricultural, etc. disruptions would be truly unprecedented. Even if “only” 1 billion people were to perish, this could be enough to catapult the whole global system into such disarray that collapse becomes unavoidable.

Climate Change

However, I’m far more worried about climate change and biodiversity loss. As noted above, these almost certainly won’t be extinctional — the probability appears very small that current rates of CO2 emissions could trigger a runaway greenhouse effect, which is what turned our planetary neighbor Venus into a hellish cauldron of flesh-melting heat. But climate change and biodiversity loss will severely damage the underlying pillars upon which the edifice of our civilization is founded. What follows is a very brief overview, which will largely skip relevant details about heatwaves and wet-bulb temperatures, ocean acidification, oceanic dead zones, coral bleaching, wildfires, megadroughts, category-6 hurricanes, mass migrations, political instability, social upheaval, and so on.

There are many estimates of how many people will die because of climate change. A World Economic Forum study from 2024 estimates that “by 2050 climate change may cause an additional 14.5 million deaths and $12.5 trillion in economic losses worldwide.” Another paper from 2023 used the 1,000-ton rule to calculate that by the end of the century, at least 1 billion people will have died prematurely. Yet another from early 2025 claims that if we reach 2-3 degrees C of warming by 2050 — which we will — then we should expect between 2 to 4 billion premature deaths. I asked one of the coauthors of this study about the figure, and he replied that “I would not have described them as (premature) deaths but I would say 2 billion people will be exposed to risk of mortality from unprecedented heat at 2.7C” based on his coauthored paper “Quantifying the human cost of global warming” in Nature Sustainability. He added that this second “paper misses a load of other sources of potentially fatal risk.”

What’s noteworthy is that estimates of the catastrophic costs of climate change tend to be increasing over time. The more climatologists understand, it seems, the more dismal their prognostications. One could say something similar about biodiversity loss: ongoing research paints an increasingly dismal picture. Consider that since just 1970, the global population of wild vertebrates (mammals, fish, reptiles, birds, amphibians, etc.) has declined by a staggering 69%. Take a moment to extrapolate this trend into the future. There is, furthermore, an emerging consensus among biologists that we’re in the early stages of the sixth major mass extinction event, and a study in Nature warns that we may be racing toward a sudden, catastrophic, irreversible collapse of the global ecosystem with huge implications for civilization.

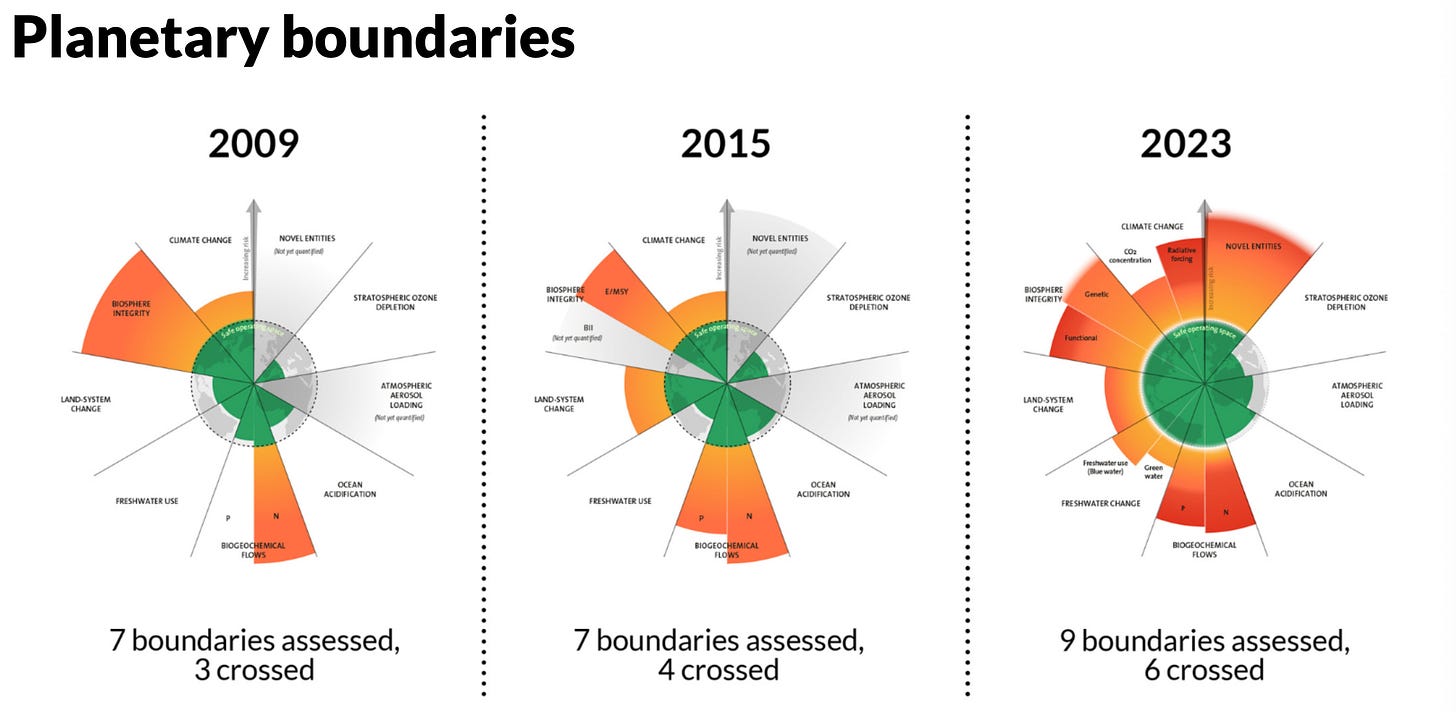

Other scientists report that we’ve cross seven of nine planetary boundaries, which demarcate a “safe space” for civilization. Still others claim that we risk triggering “tipping points” in major Earth systems that could radically alter the habitability of our planet in relatively short periods — i.e., within a single human lifetime. The extreme, rapid climate alterations (alluded to earlier) that happened in the northern hemisphere during the Younger Dryas provide a useful point of reference: yes, our species survived these sudden changes, but would a global civilization adapted to the Holocene environment? Probably not.

As I argued above, even if “only” 1 billion people were suddenly subtracted from the human population over years or decades, it’s extremely difficult to picture our civilization enduring. Hence, the environmental predicament alone is enough to conclude that civilization has an expiration date, and this date lies in the not-so-distant future. Sadly, the reelection of Donald Trump, who immediately withdrew the US from the Paris Climate Accords and claims that global warming is a “Chinese hoax,” threw whatever hope there was out the window. As I wrote in a Salon article after the record-breaking heatwaves and flooding around the world in 2023:

The disturbing fact that puts everything in perspective is that this summer will likely be among the mildest summers that you and I will experience for the rest of our lives. The extreme meteorological events of 2023 will be among the least disruptive that humanity encounters from here on out. Or to paraphrase the environmental philosopher Yogi Hendlin, the hottest summer so far on record will be one of the coolest and most stable of all the summers between now and the end of this century.

Indeed, 2024 was the hottest year on record, breaking the record previously set by 2023.

Large Language Models

The last major civilizational threat worth mentioning, in my view, is AI. Current AI systems, powered by LLMs, are enabling people to flood the Internet with plausible-sounding disinformation, conspiracy theories, AI slop, and deepfakes. In his dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell wrote: “The Party told you to reject the evidence of your eyes and ears. It was their final, most essential command.” But what happens when none of us can even trust our eyes and ears?

Computer scientist Jaron Lanier argued in The Social Dilemma that social media itself poses an existential threat to civilization: “If we go down the status quo for, let’s say, another 20 years,” he said, “we probably destroy our civilization through willful ignorance.” I’d say something similar about AI.5 If there’s no shared reality between citizens, if individuals are incapable of distinguishing between what’s real and fake, true and false, then what hope is there for tackling global-scale problems like climate change? For this reason, I see AI as a profound threat amplifier and threat multiplier that will, as such, severely undermine our chances of preventing global-scale collapse from occurring. If anything, AI will accelerate this process.

Hospice for Humanity?

So, that’s the bad news: I see no good reasons for being sanguine about the future of civilization, although the “good news” is that our species will likely survive the cataclysms to come. Given this outlook, some have recently argued that we may need to pivot toward a new “palliative care” paradigm for humanity. I used to see this suggestion as rather hyperbolic, but not anymore — especially after Trump’s reelection, because as the saying goes: “If the U.S. sneezes, the rest of the world catches pneumonia.”

In 2017, I jokingly “coined” the term superfucked to describe a situation in which catastrophe is strongly overdetermined, meaning that there are multiple possible causes leading to the same undesirable outcome. “Superfucked” is more or less synonymous with “polycrisis,” which has become widely used by scholars over the past few years. There are just so many unprecedentedly complex, formidable, urgent threats facing humanity that it’s difficult to see how civilization, as we currently know it, can make it through unscathed. I’m talking about catastrophic climate change, worldwide biodiversity loss, the sixth mass extinction, global ecological collapse, the ongoing threat of nuclear war, AI flooding our information ecosystems with memetic poison, the possibility of new emerging disease epidemics, the rise of fascism in the US and Europe, anthropogenic carcinogens, neurotoxins, and endocrine-disrupting chemicals becoming ubiquitous in our environs, and so on and so forth.6 Each of these yields a plethora of sub-problems that make the existential obstacle course before us look dauntingly dense.

This is precisely why, the argument goes, we need a palliative-care approach, a kind of hospice for humanity. While we should never give up the fight — because we have a moral duty to keep fighting even if things look hopeless — we should also seriously ask ourselves: What does it mean to live a good life in the face of collapse? How can one find meaning and purpose in this situation? What kind of communities can we build right now to protect ourselves from the physical and psychological harms of witnessing the world as we know it come crashing down around us?

It’s worth remembering that, as I wrote in a previous newsletter article, “not every doomsayer who screamed ‘The end is nigh!’ was wrong.” Lots of civilizations have in fact collapsed throughout history, as the scholar Luke Kemp observes in his excellent new book Goliath’s Curse: The History and Future of Societal Collapse. Based on nearly a decade of researching the topic, Kemp — who, I know from many personal interactions with over the years, is not one to exaggerate or make hyperbolic claims — shares my pessimism about the future of civilization. In a recent Guardian article, he’s quoted as saying:

We can’t put a date on Doomsday, but by looking at the 5,000 years of [civilisation], we can understand the trajectories we face today – and self-termination is most likely.

100% agree. Funnily enough, it seems that many tech billionaires do as well, even though they’re the ones pushing humanity toward the precipice of destruction. Mark Zuckerberg, for example, has spent literally hundreds of millions of dollars on a compound in Hawaii that includes an underground bunker, complete with blast-proof doors and an emergency escape hatch. Sam Altman is also a prepper who told The New Yorker that he has “guns, gold, potassium iodide, antibiotics, batteries, water, gas masks from the Israeli Defense Force, and a big patch of land in Big Sur I can fly to.” As Vox reports:

Reddit CEO Steve Huffman, Sam Altman of Y Combinator, Trump-loving Peter Thiel — the list goes on — are all preppers. [Reid] Hoffman estimates that “50-plus percent” of other tech billionaires have a home to escape to.7

This is perhaps the one thing that folks like me, Luke Kemp, and these obscenely wealthly oligarchs have in common: a shared belief that our current system is fated to unravel in the near future!

I’m very curious to know your thoughts. As mentioned, this is not an exhaustive treatment of the topic: a full account of why I think civilizational collapse is highly likely would require at least 10,000 words (and this post, in total, is about 5,000 words). What am I missing? How do you think I might be wrong? Do you agree that human extinction is improbable but civilizational collapse is more or less inevitable? I’m opening the comments to everyone, once again!8

Thanks so much for reading and I’ll see you on the other side!

For a discussion of the significance of 1954 for the history of thinking about our extinction, see this article of mine in the Los Angeles Review of Books.

For example, he wrote that “of the species now living, very few will transmit progeny of any kind to a far distant futurity.”

As Lord Martin Rees wrote in a foreword to one of my books, “The stakes are so high that those involved in this effort will have earned their keep even if they reduce the probability of a catastrophe by a tiny fraction.”

Indeed, there’s a synergistic relation between AI and social media: the latter provides a powerful mechanism for disseminating false information generated by the former.

If I were to have written a much longer article, I would have gone into some of these phenomena in more detail.

This is, in other words, just their version of “hospice for humanity.”

Here are some of the questions I am contemplating.

Can I/we humans - discover that real satisfaction comes from the vulnerability of loving relationship rather than from illusions of control?

Am I/ are some of us humans - willing to trust that we humans are actually a very, very small part of the “WE” of a larger co-evolving beloved community that has been around forever, and who will fold us in and continue to include us even as we become extinct?

How do I-we humans - live into this rapid, anthropogenic extinction event with love, compassion, and wisdom?

I am profoundly grateful for your work. You see and then you say what you see and you ask, what am I missing and where do we go from here?

I feel like you and Rachel Donald and Nate Hagens and others are engaged in this deep empathetic inquiry which is in service of love.

And we are here to love - only love. Nothing more, nothing less, and nothing else.

This is liberatory and yet also profoundly prescriptive for us.

I agree with the assessment that extinction events seem improbable, even if we cannot entirely rule it out.

As far as civilizational collapse is concerned, I suppose it depends on the definition of what constitutes a collapse. If we are to remain within the current societal paradigm, it does indeed seem almost inevitable that our days are numbered. However, it's not as if the question of "Revolutionary change" had not been on our Civilization's agenda for some time, again and again (with wildly varying trackrecords and as a constant undercurrent), so I would argue that a paradigm shift that would substantially alter that trajectory would not necessarily constitute a collapse.

Moreover, I kind of think that the old idea of "Pessimism of the Intellect, Optimism of the Will" sort of demands that we need to fight this "almost inevitability" tooth and nail.

In terms of How to deal with this realization, I found Margaret Killjoy's short essay on "How to live like the world is ending" rather excellent.

https://margaretkilljoy.substack.com/p/how-to-live-like-the-world-is-ending