A Revolutionary Paradigm Shift, on Par with the Copernican and Darwinian Revolutions, Is Happening Right Now and No One Is Talking About It

Over the past two centuries, especially since the 1950s, a dramatic shift has been unfolding in how we understand humanity's place in the universe. This article explains. (4,500 words)

Here’s a little mini-book about a fascinating development in recent human history, presented in 9 short chapters.

Chapter 1: Copernicus, Darwin, and Dr. Fraud

You’re probably familiar with the idea that there have been two or three great revolutions in how we understand ourselves and our place in the universe. The Copernican revolution dethroned humanity from the center of the universe. Prior to this, most people accepted a geocentric model of the universe according to which the sun, planets, and fixed stars in the sky revolve around Earth. Copernicus replaced this with a heliocentric model, whereby Earth is just another planet orbiting the sun, and the fixed stars seen flickering in the midnight firmament are their own solar systems, complete with (exo)planets orbiting their own stars.

This revolution dealt a terrible blow to the narcissism of our species. It undermined a version of anthropocentrism that we can call cosmological anthropocentrism: the idea that we hold a special, unique place within the cosmos as a whole.

The next revolution was Darwinian: since the ancient Greek philosophers, on through much of the Common Era when Christianity reigned supreme in the Western world, nearly everyone believed that humans are qualitatively different from all other creatures. Unlike nonhuman organisms, we are embodied souls and ensouled bodies. This makes us different in kind rather than degree, and it’s by virtue of this “ontological gap” that we constitute the pinnacle or apotheosis of creation. We might not be at the center of the universe, but we are the center of the biological world.

Darwin’s 1859 book On the Origin of Species demolished this idea. Although his mechanism of evolutionary change — natural selection — wasn’t widely accepted until the Modern Synthesis of the 1930s, he did manage to almost immediately convince almost the entire scientific community that evolution is a biographical fact about life on Earth. The implication is that, in fact, we differ from the rest of the Animal Kingdom by degree rather than kind. There is no ontological gap separating us from them — how could there be, if we descended from the same common ancestor as the chimpanzee and bonobo? Furthermore, Darwin showed that evolution is a-teleological, meaning that it’s not progressing toward “higher” or “better” forms, of which we are the culmination. To the contrary: we are no more evolutionarily special than the bacteria, amoebas, and tardigrades living among us.

This mortally wounded a second kind of anthropocentrism, which we can call biological anthropocentrism, and in doing so dealt another blow to our collective ego. It turns out that we’re nothing special even here on Earth!

Some scholars point to a third revolution: the Freudian revolution, which revealed that we are not in fact masters of our own mental worlds. Rather, our subconscious or unconscious mind has far more control than previously thought. For the present purposes, I’m going to mostly ignore this “revolution,” since Dr. Fraud — I mean Freud (parapraxis!) — didn’t put forward a legitimate, falsifiable scientific theory, or so many have argued. I agree with that assessment, although Freud’s work has incontrovertibly had a profound impact on how we understand ourselves.

Chapter 2: A Heady Young Cephalaspis

What I want to argue is that there’s a fourth major revolution with implications no less profound than the first two, and which no scholar — to my knowledge — has yet explicitly identified. It concerns what we might call (for lack of a better term) existential anthropocentrism. What does that mean? The term denotes the view that humanity retains a certain existential importance in the universe, rendering it unimaginable that the universe might exist without us.

Consider this passage from HG Wells’ 1894 essay “The Extinction of Man”:

It is part of the excessive egotism of the human animal that the bare idea of its extinction seems incredible to it. “A world without us!” it says, as a heady young Cephalaspis [a genus of extinct fish] might have said it in the old Silurian sea. But since the Cephalaspis and the Coccostus [another genus of extinct fish] many a fine animal has increased and multiplied upon the earth, lorded it over land or sea without a rival, and passed at last into the night. Surely it is not so unreasonable to ask why man should be an exception to the rule. From the scientific standpoint at least any reason for such exception is hard to find.

He adds:

No doubt man is undisputed master at the present time — at least of most of the land surface; but so it has been before with other animals. … [M]an’s complacent assumption of the future is too confident. We think, because things have been easy for mankind as a whole for a generation or so, we are going on to perfect comfort and security in the future. We think that we shall always go to work at ten and leave off at four, and have dinner at seven for ever and ever. But these four suggestions [a reference to four ways that we could die out, according to Wells], out of a host of others, must surely do a little against this complacency. Even now, for all we can tell, the coming terror may be crouching for its spring and the fall of humanity be at hand. In the case of every other predominant animal the world has ever seen, I repeat, the hour of its complete ascendency has been the eve of its entire overthrow.

This is existential anthropocentrism: it just can’t be the case that our species disappears like 99.9% of all previous species. It’s unimaginable, unthinkable, outrageous. As Immanuel Kant wrote in 1790, without us, the universe would be incomplete — a “mere wasteland, gratuitous and without a final purpose.”

The fourth revolution, then, is the dawning realization that the universe doesn’t need us. If humanity were to go extinct, it would carry on without us, as if nothing had happened and we had never even been. The universe is indifferent to our survival. This is yet another devastating blow to the egotism of our species: we aren’t located at the center of the cosmos; we don’t constitute the pinnacle of evolution; and we’re so unimportant in the grand scheme of things that we could die out tomorrow and the universe wouldn’t even notice.

Chapter 3: Living Through the Fourth Revolution

How has this fourth revolution unfolded? A little differently than the first two (again, ignoring the Freudian revolution). As the eponymous names of these revolutions indicate, they were catalyzed by two particular individuals: Copernicus and Darwin. The fourth revolution is the result of a huge number of people and three cultural-intellectual developments, which I’ll discuss momentarily. Scientists, philosophers, novelists, and poets all contributed.

Furthermore, whereas the Darwinian revolution unfolded quite rapidly — as noted, Darwin almost immediately convinced most scientists that evolution is a fact about the biological world — this fourth revolution has developed rather slowly since the 1800s, and is still ongoing. We’re in the midst of it right now, witnessing the idea of human extinction become more widely discussed and accepted in realtime. As I write at the very beginning of my big book Human Extinction, even many children will affirm that humanity could go extinct like the nonavian dinosaurs did 66 million years ago.

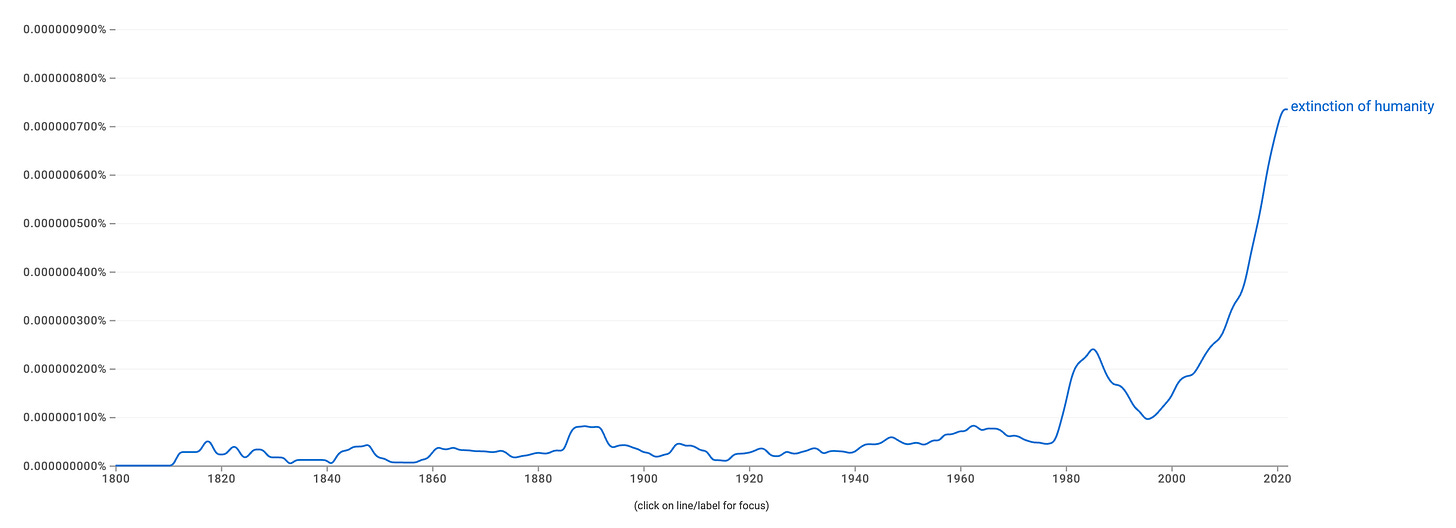

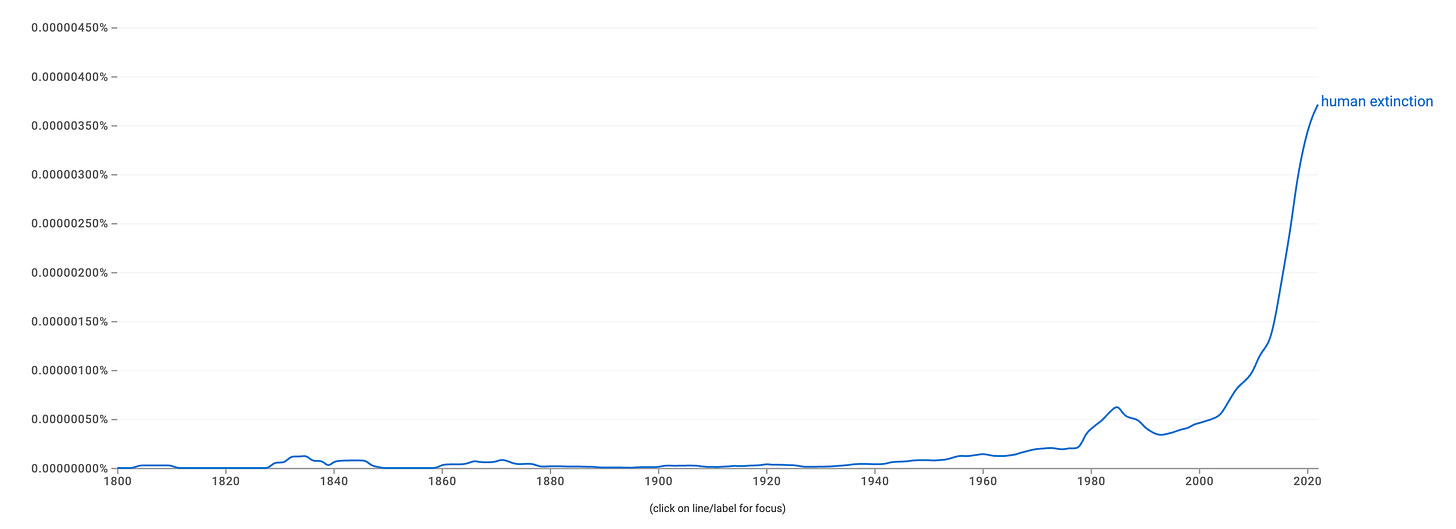

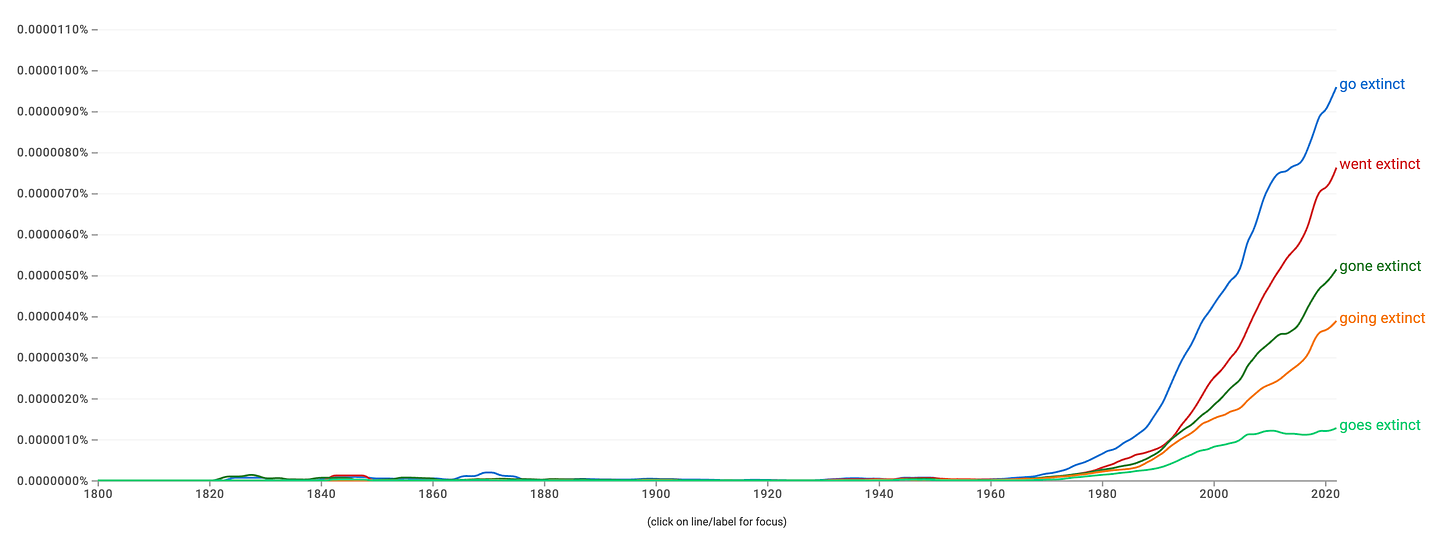

Or consider these Google Ngram Viewer graphs, which chart the frequency of the term “human extinction” over time within Google’s vast corpus of digitized texts:

This constitutes a monumental shift, which almost no one is talking about — or has even explicitly recognized. Never before in all of human history has the idea of human extinction been more widely discussed, debated, and taken seriously than right now. The fourth revolution is happening before our very eyes, eliciting the same kind of psycho-cultural trauma that the other two did.

Chapter 4: An Origin Story

How did this revolution begin? When did it start? If one defines “human extinction” as a future state in which no humans exist (minimal definition), then the idea dates back to the Presocratic philosophers. For example, Xenophanes and Empedocles both posited cyclical cosmologies according to which the cosmos oscillates between different stages, at least one of which involves humanity disappearing. However, due to the fundamental nature of the cosmos, humanity will always reappear in the future. This is why, somewhat surprisingly, the idea of human extinction is compatible with the idea of human indestructibility.

Others, like the Stoics, believed in the eternal return: the universe will someday be destroyed in a great conflagration (an idea called “ekpyrosis”), but after this the world will reemerged and every person who once existed will live their lives exactly as they did before. Finally, the ancient atomists believed that all “worlds” (basically, solar systems) will be destroyed, meaning that human extinction is inevitable. But they also held that the universe is infinite, and hence that over enough time new worlds will emerge exactly like ours. Humanity would then reappear elsewhere. In this sense, we are once again indestructible.

These are absolutely fascinating examples of people predicting human extinction — on a minimal definition — literally thousands of years ago. Then, something momentous happened that would render the idea of human extinction completely unthinkable for some 1,500 years: Christianity came to dominate the Western world in the 3rd and 4th centuries CE. There are two reasons that Christianity is incompatible with the idea of human extinction, whereby humanity disappears entirely and forever (on a slightly stronger conception).

The first concerns the idea that we have immortal souls, which is precisely what Darwin’s theory of evolution severely undermined. The reasoning goes like this: if all humans are immortal, then humanity as a whole is immortal, and if humanity as a whole is immortal, then human extinction is impossible. Because philosophers like to sound smart by using big polysyllabic terms, I call this the ontological thesis.

The second arises from the fact that Christian eschatology (the study of the end of the world as we know it): our extinction simply isn’t part of God’s grand plan for the cosmos. In the end, Good will triumph over Evil and the scales of cosmic justice will finally be balanced as God punishes the wicked and rewards the righteous with eternal life in heaven. How could the scales of cosmic justice be balanced if we were to disappear? How could the narratives of salvation and redemption reach completion without us? Let’s call this the eschatological thesis.

These two ideas were enough to make human extinction unthinkable. It wouldn’t even have been seen as a coherent idea, not unlike the way concepts like married bachelor and circles with corners are incoherent. Since humanity is immortal, saying that humanity could go extinct would be to say that something that, by its very nature, can’t go extinct could go extinct!

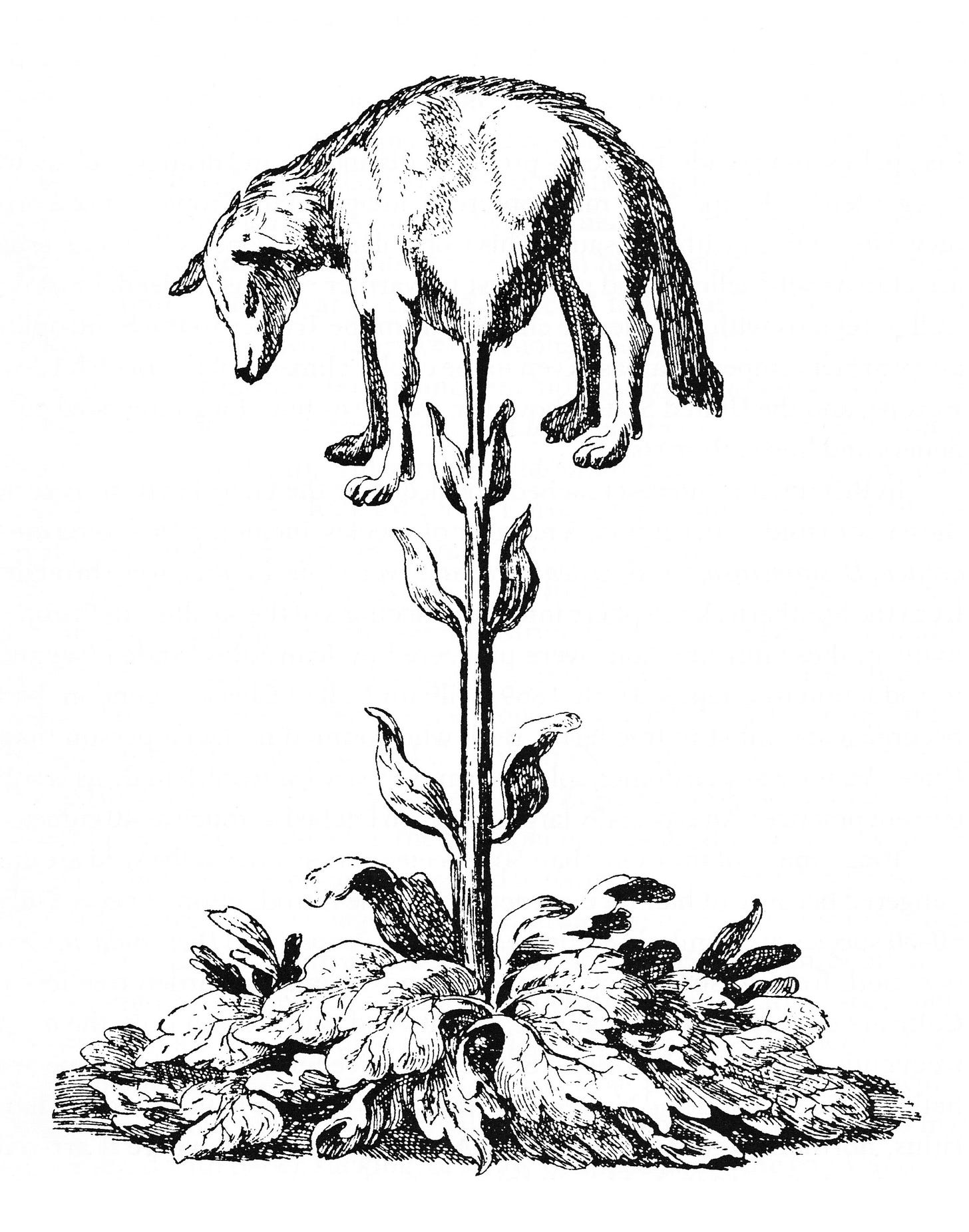

Yet, there was another idea that also rendered the idea of human extinction absurd: the Great Chain of Being. This emerged in the 3rd century CE with Neoplatonists like Plotinus, and was quickly incorporated into Christianity. The basic idea is that every kind of thing that could exist does exist. It’s literally why some people — I kid you not! — accepted the existence of mermaids, as transitional species between humans and fish. (Hence, in 1689, John Lock wrote: “Amphibious animals link the terrestrial and aquatic together … not to mention what is confidently reported of mermaids or sea-men.” This is also why people believed in “zoophytes” like the Vegetable Lamb of Tartary, a plant that grows sheep as fruit! Here’s an illustration of the plant-animal hybrid:

The Great Chain of Being sounds pretty ridiculous to modern ears, but it had a truly profound impact on Western thinking for millennia. Its relevance to our discussion of the fourth revolution is this: the fullness of nature, the fact that every kind of thing that could exist does exist, is evidence of God’s perfection. Hence, if even a single link in the Great Chain were to go missing, it would imply that God is imperfect — which, of course, he’s not. It follows that the extinction of any species is fundamentally impossible. And since humanity is one kind of species, our extinction is fundamentally impossible.

The Great Chain collapsed rapidly in the very early 1800s, thanks largely to the innovative work of Georges Cuvier, who showed beyond a reasonable doubt that species like the mammoth and mastodon (that latter of which he named) are now extinct. Before Cuvier, no one believed this! In fact, Thomas Jefferson was so convinced that the mammoth still exists somewhere on Earth — because he accepted part of the Great Chain model of reality — that he instructed Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to gather evidence of the mammoth’s continued survival in the western parts of North American on their famous Lewis and Clark Expedition.

With the fall of the Great Chain, conceptual space began to open up for the idea of human extinction. But the ontological and eschatological thesis remained, both of which (as noted) imply that our extinction simply can’t happen, ever.

However, it wasn’t long after the Great Chain imploded that these theses were also seriously undermined. As the 19th century progressed, Christianity declined markedly among the educated classes (due in part to Darwin’s evolutionary theory, along with the rise of biblical criticism and new interest in theological issues like the problem of evil). Recall that this was the century in which Marx denigrated religion as the “opium of the masses” and Frederich Nietzsche famously declared that “God is dead.”

For the first time since Christianity became the “state religion” (as it were) of the Roman Empire, atheism started to become widely embraced by intellectuals. Consequently, the last two obstacles that prevented people from acknowledging the possibility of human extinction were removed. No longer was our extinction unthinkable to most people in the West — a truly colossal shift in perspective.

Chapter 5: Snowhuts Near the Equator

All that was missing was a specific reason to seriously consider the possibility of our extinction. This came in the early 1850s with the discovery of the second law of thermodynamics. Immediately, physicists recognized the terrifying implications: Earth would someday become uninhabitable and humanity would die out. It’s hard to overstate how psycho-culturally traumatizing this was, as a very large number scientists, philosophers, and writers bemoaned the eventual demise of our species. As one person wrote in 1883:

Species after species of animals and plants will first degenerate and then become extinct, as the worsening conditions of life render it impossible for them to continue the struggle for existence; a few scattered families of degraded human beings living perhaps in snowhuts near the equator, very much as Esquimaux live now near the pole, will represent the last wave of the receding tide of human existence before its final extinction; until at last a frozen earth incapable of cultivation is left without energy to produce a living particle of any sort and so death itself is dead.

The celebrated philosopher Bertrand Russell (more or less plagiarizing an earlier article by Alfred Balfour) said this in his 1903 essay “A Free Man’s Worship”:

All the labours of the ages, all the devotion, all the inspiration, all the noonday brightness of human genius, are destined to extinction in the vast death of the solar system, and that the whole temple of Man’s achievement must inevitably be buried beneath the debris of a universe in ruins.

Here, then, are the origins of the fourth great revolution. The Great Chain collapsed, Christianity retreated, and scientists discovered that humanity has an expiration date stamped on its forehead due to the second law. For the first time ever, people were forced to confront the dismal reality of our shared fate. We are not so special as we once thought; we are not a permanent fixture of the universe.

Indeed, Wells’ essay on the extinction of humanity was published shortly before Russell’s reflections on the mortality of our species (and how this apparently renders our efforts meaningless in the grand scheme of things). It’s notable as an expression and articulation of the psychological struggles of so many at the time: What if our existential predicament is no less precarious than that of other species? How does one psychologically deal with this dreadful realization and still find meaning in life?

Chapter 6: Anxieties About Science and Technology

The Great Chain, ontological thesis, and eschatological thesis were conceptual barriers to thinking about human extinction. The second law of thermodynamics was the first scientifically credible kill mechanism, which initiated a flurry of discussions about the inevitability of human extinction.

In the decades following the second law’s discovery, many people suggested other possible kill mechanisms. The science fiction author Jules Vernes proposed quite possibly the first technological doomsday scenario in his 1863 novel Five Weeks in a Balloon, whereby one character suggests that “the end of the earth will be when some enormous boiler … shall explode and blow up our Globe!” But no one took this seriously as a way we could die out, nor was it intended as a plausible doomsday scenario.

However, the First World War — with its tanks, chemical weapons, machine guns, and flamethrowers — made many folks rethink the possibility of anthropogenic extinction. Perhaps “progress” in science and technology is actually leading us toward the precipice of annihilation. In a 1924 essay, Winston Churchill argued that humanity “has got into its hands for the first time the tools by which it can unfailingly accomplish its own extermination.” Freud closed his 1930 book Civilization and Its Discontents with the warning: “Men have brought their powers of subduing the forces of nature to such a pitch that by using them they could now very easily exterminate one another to the last man.”

Even more, many scientists in the early 20th century believed that we may be on the cusp of inventing a technology that can convert — or transmute — one chemical element into another. If such a technology were created, it might turn the entire planet into a puff of hydrogen. Some even speculated that this “planetary chain reaction” could extend beyond Earth, destroying the entire universe. In his 1935 Nobel Prize speech, Frédéric Joliot-Curie even speculated that nova — seen as a sudden bright dot in the sky — might be other advanced civilizations inadvertently destroying themselves through this process!

These anxieties pointed toward a real — and extremely ominous — trend: science and technology have radically expanded our capacity for violence, destructive, and annihilation. Most of them, however, were hyperbolic: no one was actually worried that chemical weapons, flamethrowers, etc. would destroy humanity. I think what these authors were really talking about — using exaggerated language — was the destruction of civilization rather than complete human extinction. Furthermore, there was no known way to transmute all the atoms in Earth into something else, and it turns out that this fear, which I wrote about in Salon here, was entirely wrongheaded: no such threat actually existed.

Chapter 7: The Debut of Doomsday Technologies

Things changed dramatically in the 1950s with the invention of thermonuclear (hydrogen) weapons. You might think that 1945 would have caused people to worry about human extinction, but that simply wasn’t the case: almost no one connected atomic bombs of the sort used on Hiroshima and Nagasaki with extinction. People did worry about societal collapse, but not the elimination of our species entirely.

As I discuss in this article for the Los Angeles Review of Books, what happened in the 1950s was a very specific event that suddenly and radically changed the way people thought about nukes: in 1954, two years after thermonuclear weapons were invented, the US detonated one of these bombs in the Marshall Islands. This was the famous Castle Bravo test. It produced an explosive yield 2.5 times larger than expected (whoops!), spreading radioactive particles around the entire globe. Immediately, scientists, philosophers, and public intellectuals started shouting that even a small-scale thermonuclear war could kill everyone on Earth by blanketing our planet with radioactivity. Most people wouldn’t die at first. Rather, radioactivity would cause genetic mutations that result in “a slow torture of disease and disintegration.” Basically, our species would degenerate over generations, as children would have monstrous mutations that eventually render their survival (or the survival of their children, etc.) impossible.

The quote above comes from the Russell-Einstein Manifesto, written in direct response to the Castle Bravo debacle. (It was, in fact, the last thing that Einstein signed just before his death — a truly incredible story that I’ll save for another time!) Russell and Einstein warn that thermonuclear weapons could lead to the “universal death” of humanity. They write:

Many warnings have been uttered by eminent men of science and by authorities in military strategy. None of them will say that the worst results are certain. What they do say is that these results are possible, and no one can be sure that they will not be realized. We have not yet found that the views of experts on this question depend in any degree upon their politics or prejudices. They depend only, so far as our researches have revealed, upon the extent of the particular expert’s knowledge. We have found that the men who know most are the most gloomy.

That last sentence is quite haunting (to me, at least), but true at the time: most experts agreed that thermonuclear weapons pose an existential threat. This is evidenced by the fact numerous world-renowned scientists, including Frédéric Joliot-Curie, cosigned the manifesto.

Chapter 8: A Panoply of Perils. Or: Welcome to the 21st Century!

Since then, we’ve seen a veritable explosion of new kill mechanisms be discovered or created, with each new mechanism further catapulting the idea of human extinction to prominence. In the early 1980s, scientists discovered that nuclear weapons could also induce a “nuclear winter,” whereby the soot from burning cities spreads around the world and blots out incoming light from Earth. Humanity could perish in literally pitch-black skies at noon and subfreezing temperatures in the summer. Worries about ecological collapse arose in the 1970s and 80s (following Rachel Carson’s 1962 book Silent Spring), and of course ozone depletion — if it hadn’t been detected when it was — could very well have resulted in none of us being alive right now. Others began to speculate about the possibility of genetically engineered pathogens, and a few people in the late 1950s and 60s, such as I. J. Good, claimed that advanced artificial intelligence could usher in a utopia or obliterate us.

Then, in the 1980s, scientists discovered that large asteroids can slam into Earth and cause mass extinctions, a view that virtually no one had accepted since the 1830s or so. By the 1990s, a consensus was reached that global-scale catastrophes caused by natural phenomena are possible. Around the same time, volcanologists discovered volcanic supereruptions, and in the early 1990s some began speculating that our species nearly went extinct due to a volcanic supereruption in Indonesia about 75,000 years ago, called the Toba catastrophe.

Fast forward to the late 1990s and early aughts, we find a consensus emerging about climate change, along with more elaborate speculations about advanced genetic engineering, molecular nanotechnology, and artificial superintelligence (ASI). In his 2000 article published in Wired, titled “Why the Future Doesn’t Need Us,” the technologist Bill Joy argued that these technologies pose such an immense, unprecedented threat to our collective survival that we should impose broad moratoria on entire fields of emerging science and technology.

This brings us to the present, when it’s hard to go a week without glancing at the news and seeing some new story about how ASI could cause our extinction. Simultaneously, environmental scientists and climatologists are shouting with ever-greater intensity about the profound dangers of climate change, biodiversity loss, and the sixth major mass extinction in life’s 3.8-billion-year history on Earth, with some suggesting that the outcome could potentially be the elimination of our species.

Add to this the rise of what I call Silicon Valley pro-extinctionism, the view that we should create ASI to completely replace humanity in the near future. In other words, we should accelerate the Singularity so that “better,” “superior” beings can take our place and proceed to conquer the universe — an idea associated with what I call digital eschatology. If you’d like to learn more about this, see my 3-part series on the topic for this newsletter. Some people in the field of AI are even claiming that it’s “fundamentally unethical” to have children because, well, what’s the point? The human era is coming to an end, superseded by a new posthuman age of superintelligent AIs.

Chapter 9: An Extraordinary Turn of Events

This is how the fourth great revolution in our thinking about humanity’s place in the universe is unfolding before our eyes. It wasn’t that long ago — just two centuries or so — that almost no one in the Western world would have said that human extinction is even possible. Most would have said the idea is simply incoherent — no different from claiming that circles can have corners. Now, a very large number of people acknowledge that we are no more a permanent fixture of the universe than the dodo and dinosaurs were. Even children recognize this. Some people are even arguing that we ought to go extinct by replacing ourselves with ASI.

This is an extraordinary turn of events. It’s a huge blow to existential anthropocentrism, following the demolition of cosmological and biological anthropocentrism by Copernicus and Darwin. What kind of anthropocentrism is left?

Here you might point out that a few minor revolutions have occurred alongside these Big Three: for example, in the 1970s, philosophers introduced the idea of biocentrism, the idea that — to put it somewhat academically — humans are not the center of the axiological universe. By that I just mean that we aren’t the only beings with value, and the value of other beings (nonhuman organisms) is independent of the value we attribute to them. For example, you might say that the forest near your home is valuable because you go for salubrious walks in it. Biocentrists would say that the creatures living in the forest, and perhaps the forest itself (ecocentrism), have value in and of themselves — not because they’re instrumentally useful to you or me. This constitutes a minor dethroning of humanity from the center of value.

You might also say that the creation of AI that can convincingly mimic human language is a kind of dethroning: prior to the large language models (LLMs) that power ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, Grok, etc., we tended to think of ourselves as special and unique because of our ability to produce language. But now we have AI systems that can understand and generate language as well as humans, which further undermines our narcissistic sense of self-importance. You could even see the rise of Silicon Valley pro-extinctionism as a kind of opposition to all forms of anthropocentrism: we aren’t the center of the universe, the pinnacle of creation, or some kind of permanent feature of the cosmos — nor should we be. Our role in the grand eschatological scheme is to give birth to superior beings that can become the center of the universe by colonizing every galaxy that it contains.

Where will this fourth revolution lead us? It’s worth noting that, while virtually everyone around the world these days accepts the heliocentrism of Copernicus, not everyone accepts the evolutionary materialism of Darwin. In this sense, the Darwinian revolution never reached completion, unlike the Copernican revolution. The fourth revolution might never reach completion either, because religion — by which I mean nearly all religions — are incompatible with the possibility of human extinction, understood as the complete and permanent disappearance of our species. Hence, so long as religion dominates the worldview of people, those people will not accept that human extinction could happen. Given that religion is on the rise globally (as well as within Western nations), it’s possible that the incipient fourth revolution never really goes anywhere. Time will tell.

What do you think of this? What am I missing? What am I wrong about? I’d really like to know your thoughts, if you made it this far! As always:

Thanks so much for reading and I’ll see you on the other side!

No doubt that these scenarios stoke fear in the hearts of those (mostly unconsciously) steeped in Western philosophy and worldviews (especially scientific materialism). Perhaps this is your intended audience, but many other cultures and traditions (notably those from Asia because they left plenty of written records, but also those that have been rendered physically extinct by or assimilated into "Western civilization") have always considered life (and humanity) to be cyclical/transitory and also "unpindownable."

"Humanity" is a conceptual construct, a product of mind, not something found "out there"--it, like any other concept, does not withstand analytical and empirical deconstruction, as Buddhist philosophers like Nagarjuna and Vasubandhu have demonstrated. That's not a nod to nihilism--on the contrary!--but a plea not to take concepts too seriously because doing so invariably creates mental halls of mirrors from which it becomes very difficult to escape.

I suppose there is debate as to whether or not Buddhism is a religion, but this essay reproduces my pet peeve of equating Christianity with religion as such (and it treats Christianity as a kind of monolith, but that's another issue). But Buddhism puts impermanence at the center of its worldview and develops spiritual practices to help us come to terms with it. So there is at least one religion that has a kind of extinctionism - and an acceptance that extinction is better than the suffering that attends existence - that is central.