Is AI Apocalypticism Really that Different from Believing in the Rapture?

On the failure of prophecies.

Enraptured by Prophecies

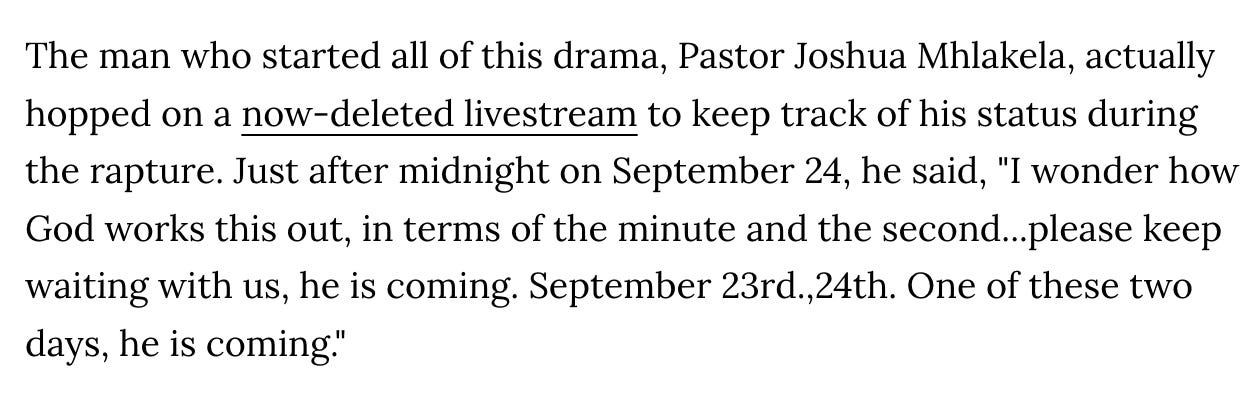

Happy post-Rapture day! According to the South African pastor Joshua Mhlakela, Jesus personally revealed to him that the Rapture would happen on September 23 or 24 of this year.

What is the Rapture? It’s not the same as the Second Coming of Christ, according to dispensationalist eschatology. The Rapture is when Jesus temporarily swoops down from the clouds to collect all Christian believers who’ve lived since 70 AD, when the Second Temple was destroyed by the Romans. Those alive during the Rapture will be “caught up” in the clouds with Jesus, while the deceased will be resurrected. After this, the Antichrist will rise up and sign a 7-year peace covenant with Israel, and the Tribulation will commence: a period of the same length during which God’s wrath will reign down on Earth (and, especially, the Jewish people). The Antichrist will then “rule with absolute authority during the second half of the tribulation,” called the Great Tribulation. This culminates with the Battle of Armageddon, when Jesus returns (the Second Coming) with an army of righteous believers to cast the Antichrist into the Lake of Fire. The 1,000-year Millennial Kingdom then begins, at the end of which Satan is loosed from bondage to fight God in the Grand Battle, which ends with God defeating Satan and recreating the entire heavens and Earth. Heaven on Earth is then established, and believers live forever with God in perfect bliss.

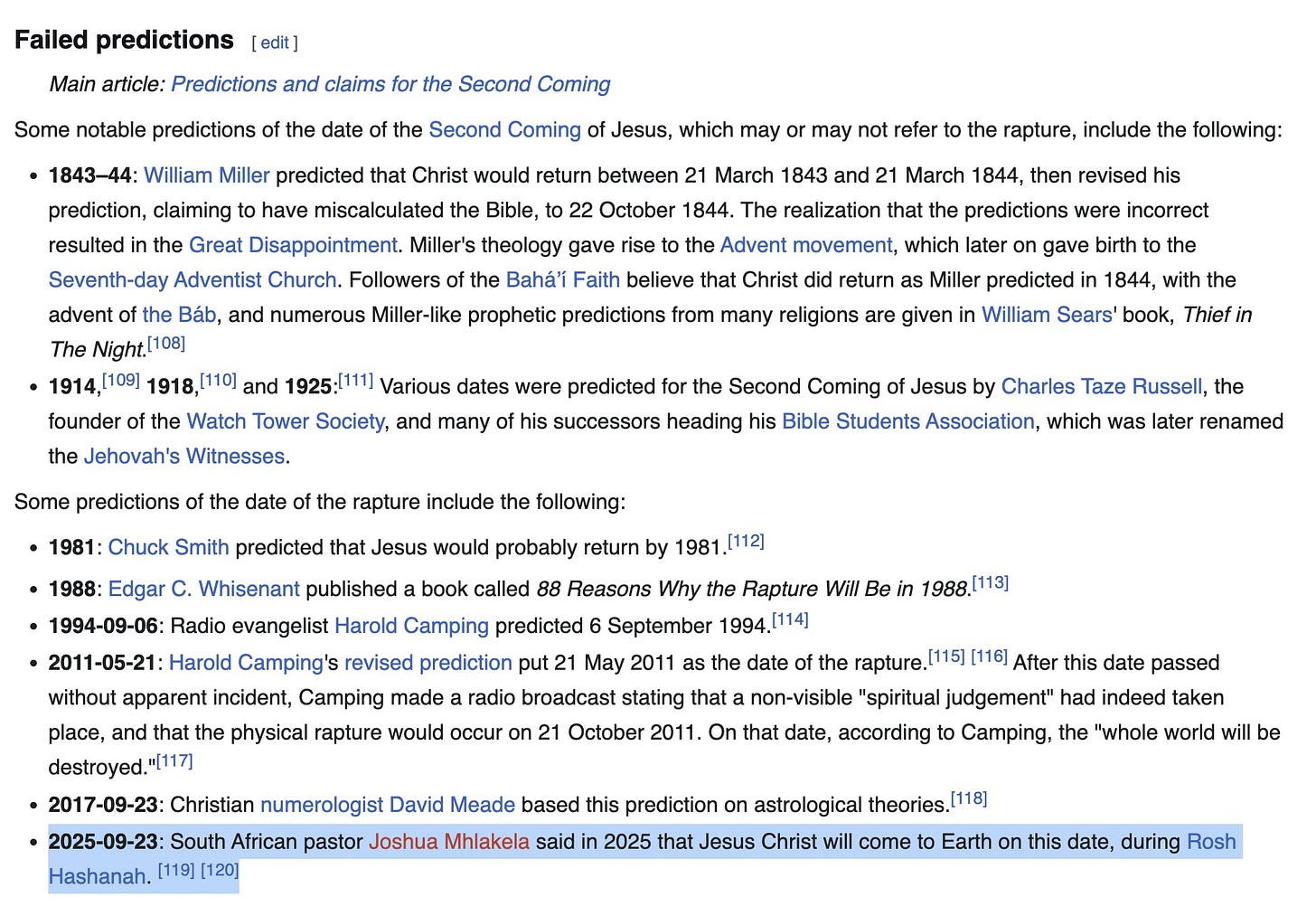

Note that the word "Rapture" doesn't appear once in the Bible. It was introduced by a particular interpretation of scripture called "dispensationalism," invented in the 1830s and promoted most notably by the Anglo-Irish Bible teacher John Nelson Darby. Dispensationalism was not widely accepted by the American public until the 1970s, due to Hal Lindsay's 1970 book The Late Great Planet Earth, which I discuss more below.Mhlakela’s prophecy received a lot of attention on social media websites like TikTok. Many people seemed to buy into it, while others took to mocking those who, for example, sold some of their possessions in anticipation of leaving behind the mortal coil of earthly existence. My favorite response to this prophecy came from Wikipedia, which, on September 22, had already listed Mhlakela’s claim in the “Failed predictions” section of its entry on the “Rapture.” Lolz.

The Power of Apocalyptic Prognostications

In my previous article for this newsletter, I argued that eschatological (or end-times) thinking has a certain seductive, intoxicating appeal because it offers a profound source of hope in the face of life’s endless miseries and injustices. Worry not, for this weary world of sin and suffering will soon come to an end, the scales of cosmic justice will finally be balanced, and the righteous will be rewarded with eternal life in paradise. I then warned that nefarious figures like Peter Thiel can exploit or weaponize the power of this thinking for political ends, as has happened many times throughout history. This is why Thiel has been talking about the Antichrist and Armageddon — or so I argued. You can listen to that article here:

Something I didn’t mention concerns the intoxicating influence of specific apocalyptic predictions, such as Mhlakela’s. Consider the fact that history is littered with failed prophecies that the end is nigh. Over and over again, people screamed that the Rapture, Second Coming, or whatever, are imminent, only to be embarrassed by the conspicuous lack of fire reigning down from heaven.

One of my favorite examples comes from the Millerites, an 18th-century movement that gained traction in the US, Europe, and even Australia. According to the American Baptist preacher William Miller, the Second Coming of Christ would occur “on or before 1843.” When this failed to happen, he pushed the date back to early 1844. When that date passed without incident, a Millerite follower named Samuel Snow offered what many movement members found to be a rather compelling argument, based on the calendar of the Karaite Jews, that the Second Coming would actually happen on exactly October 22, 1844. New prophecy dropped, and the Millerites picked it up and ran with it!

But October 22 came and went, leaving many followers in a state of inconsolable dejection — an event now called the Great Disappointment. As I write in my book The End: What Science and Religion Tell Us About the Apocalypse:

As the October date approached, some Millerites “failed to plow their fields because the Lord would surely come ‘before another winter.’ ” This belief “grew among others in [the] area so that even if they had planted their fields they felt it would be inconsistent with their faith to take in their crops.”

When Jesus failed to emerge from the clouds, many sank into a gloomy despondence. One poor Millerite wrote: “I waited all Tuesday and dear Jesus did not come; — I waited all the forenoon of Wednesday, and was well in body as I ever was, but after 12 o’clock I began to feel faint, and before dark I needed someone to help me up to my chamber, as my natural strength was leaving me very fast, and I lay prostrate for 2 days without any pain — sick with disappointment.” Another recorded the experience like this: “The 22nd of October passed, making unspeakably sad the faithful and longing ones; but causing the unbelieving and wicked to rejoice. All was still. … Everyone felt lonely, with hardly a desire to speak to anyone. Still in the cold world! No deliverance — the Lord [did] not come!”1

There are literally hundreds of examples like this — a multiplicity of “great disappointments.” For example:

The 2nd-century Church Father Irenaeus predicted that Jesus would return in 500 AD.

The bishop Martin of Tours (316/336 – 397 AD) declared that “there is no doubt that the Antichrist has already been born. Firmly established already in his early years, he will, after reaching maturity, achieve supreme power.”

As the first millennium approached, a wave of apocalyptic expectations swept across the Christian world based on a reading of Revelation 20: 1-3 and Saint Augustine’s claim that Satan had been bound “as a result of the victory won over him by the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus the Christ.”

Martin Luther claimed that the world would end at least by the year 1600.

The Catholic Apostolic Church predicted that the Second Coming would happen before all 12 of its original founders had died — the last of whom perished in 1901.

Hal Lindsay (mentioned above) argued in The Late Great Planet Earth — the bestselling “nonfiction” book of the entire 1970s, which popularized the dispensationalist reading of scripture within American culture — that the end is nigh, later declaring that “the decade of the 1980s could very well be the last decade of history as we know it.”

Edgar Whisenant also claimed that the Rapture would happen in the 1980s — in 1988, to be exact — declaring that “only if the Bible is in error am I wrong.” He claimed this would happen on Rosh Hashanah of that year, which is, incidentally, exactly when Mhlakela claimed it would happen this year.

Harold Camping subsequently predicted the Rapture would happen in 2011, and …

The American preacher Ronald Weinland prophesied that Jesus would return on June 9, 2019.

Given the ignominious history of failed apocalyptic predictions, why on Earth do people still believe new predictions like Mhlakela’s? The answer is simply this: What if this time is different? When one considers the stakes — eternal life or damnation, being “left behind” with the unholy masses, etc. — this question can be incredibly intoxicating. Behind it one finds the dizzying logic of Pascal’s wager: even if there’s only a tiny probability that this new prophecy is true, one should still take it seriously, as dismissing it could potentially imperil one’s immortal soul.

I myself felt the pull of Harold Camping’s 2011 prediction: at that time, I was firmly in the atheist camp with respect to the Christian God. Yet there was something that bothered me about it: what if … what if I’m wrong? What if this time really is different? How comfortable am I taking that risk? I knew that believing in Camping’s prediction was utterly absurd — I thought this at the time — but I couldn’t shake a bit of anxiety about it given the stakes of the wager. The power of eschatological thinking, and the ways in which particular prophecies can hypnotize, still held sway, despite me having apostatized my faith many years earlier.

AI Apocalypticism and the Techno-Rapture

As it happens, one finds this exact same kind of reasoning within the millenarian movement that Dr. Timnit Gebru and I call TESCREALism. In fact, noted TESCREALists like Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nick Bostrom have written about what they call “Pascal’s mugging.” The only difference between Pascal’s mugging and Pascal’s wager is that the former involves enormous but finite stakes, rather than infinite stakes.

The psychological pull of prioritizing “existential risk mitigation” is predicated on this logic: an existential risk is any event that would permanently prevent us from creating a multi-galactic utopian civilization among the stars full of literally “astronomical” (though finite) amounts of “value.” If an existential catastrophe were to occur, it would foreclose the creation of heaven in the literal heavens, and preclude the possibility of true believers attaining personal immortality. It follows that even if the probability of an existential catastrophe (due to, say, an artificial superintelligence takeover) is minuscule, we should still allocate lots of our resources to mitigating the risk because the expected value is so high. A tiny probability multiplied by a HUGE payoff can still yield a large number — the expected value.

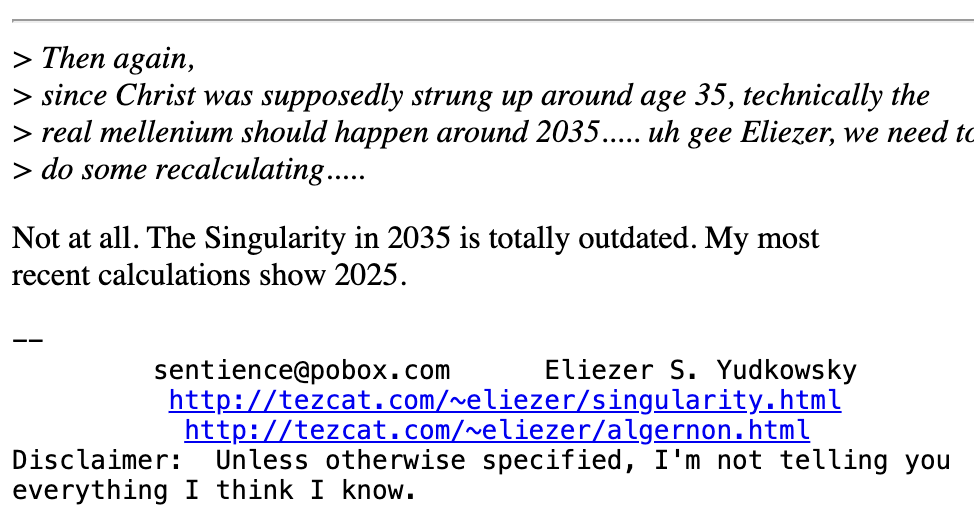

That being said, the field of AI has a long track record of failed predictions — just like Christianity. After the 1956 Dartmouth workshop that established the field, many participants became convinced that human-level AI would emerge within one generation. In 1970, Marvin Minsky claimed that AI would become generally intelligent in 3 to 8 years. In the early aughts, Eliezer Yudkowsky prognosticated that the Singularity would happen in 2025.

None of these predictions (and there are lots more) came true,2 of course, but this hasn’t stopped people in the TESCREAL movement from freaking out over new claims that AGI is imminent. Because, you know, what if this time is different? Given the existential stakes involved (controllable AGI = utopia; uncontrollable AGI = extinction), TESCREALists with an apocalyptic mindset continue to give credence to claims about the “techno-Rapture” being just around the corner — as some critics dub the Singularity.

For example, Leopold Aschenbrenner claims that AGI will arrive by 2027, while Daniel Kokotajlo, Scott Alexander, and others have independently come to the same conclusion. Like the Millerites, though, Kokotajlo recently pushed back his predicted date of arrival to 2028, and then again to 2029 (and he’ll no doubt push the date back yet again as it becomes clear that “God-like AI” is not imminent). Rather humorously, Yudkowsky’s Machine Intelligence Research Institute (MIRI) is so convinced that the techno-Rapture (Singularity) will soon arrive that it “doesn’t do 401(k) matching, because … they believe that AI will be ‘so disruptive to humanity’s future — for worse or for better — that the notion of traditional retirement planning is moot.’”

My claim here isn’t that AGI definitely won’t arrive within two or three years, although I think that’s highly unlikely. Rather, the lesson is that one should be extremely wary of apocalyptic predictions, because entering into an “apocalyptic” or “millenarian” mindset can lead one to believe outlandish ideas with far more confidence than is actually warranted by the evidence.

Word of the day: kakistocracy, meaning “government by the least suitable or competent citizens of a state.”

Thanks for reading and I’ll see you on the other side!

As it happens, the Seventh-day Adventist Church emerged out of the Millerite movement.

Yudkowsky’s 2025 prediction could still come true, of course, but no one seriously thinks that’s going to happen.

There are many reasons for wanting to immanentize the eschaton etc and one is that many of us still tell the Story of the Cosmic War. A war between ultimate good and ultimate evil taking place on both the metaphysical and physical planes, due to end very soon and with our side as the winners. We’ve been doing this since the beginning of Zoroastrianism. It’s a story with undeniable psychological heft and there was a time when it progressed religious thought because it told us we mattered, our moral actions affect history and the cosmic order. However even the tech bros have fallen into it, you don’t need religion to carry it on. It’s time we stopped telling us this story and learned to love the world and address the very real issues that face us. As usual you have written the article I wanted to write, dang you are good at this!

Émile, I enjoyed this post, thank you.

One question for you: you mock Kokotajlo for pushing back his AGI timeline from 2027 to 2029, as being an example of Millerite "moving the goal posts".

However, Kokotajlo is doing this in advance of the predicted date, based on the progress he's seeing. The Millerites only changed their dates after the dates had come and gone.

That seems like a big difference in terms of whether they are treating is as a Rapture-like event vs. one that can be semi-reliably anticipated by looking at the evidence.