Effective Altruism Is a Dangerous Cult — Here's Why

Understanding the "Scientology of Silicon Valley." (8,400 words)

My apologies for this article being so long. It aims to provide an in-depth examination of the ways in which the Effective Altruism movement instantiates a cult. I hope you find it interesting and useful!

Effective altruism has become something of a secular religion for the young and elite. — Charlotte Alter, writing in Time magazine

Since 2022, I have spoken with a large number of journalists about Effective Altruism and its Bay Area-sibling, Rationalism. For those new to the subject, these communities constitute the “EA” and “R” in “TESCREAL,” which denotes a constellation of overlapping ideologies that have become hugely influential within Silicon Valley. Dr. Timnit Gebru and I argued last year that they are largely responsible for launching and sustaining the ongoing race to build superintelligent “God-like AI.”1 In what follows, I will focus primarily on EA, though much of what I say applies just as well to Rationalism and other TESCREAL ideologies.

Over and over again, these journalists asked me: “Is EA a cult?” Prior to 2022, I would say that aspects of this movement are cult-like. However, by the end of 2022, my answer was an unambiguous: “Yes, EA is definitely a cult, with its own doctrines and dogmas, charismatic leaders, jargon, and eschatological narratives.” But I never got around to writing a comprehensive explanation of why my answer changed. This article, in more than 8,000 words, provides that explanation. My guess is that most people will agree with my view by the end of this piece.

Being Effectively Altruistic

My initial impression of EA was very positive. Unlike most EAs, I didn’t exactly join the movement. It was more like the movement found and adopted me. Why? Because I had been working on “existential risks” since about 2009, a couple of years before the EA movement emerged. Initially, EA’s focus was alleviating global poverty, but as the academic Mollie Glieberman shows, leading EAs quickly discovered the idea of existential risks (events that would prevent us from creating a techno-utopian paradise among the stars) and realized that the best way to do the most good in the world is actually reducing such risks, rather than helping poor people or eliminating factory farming.

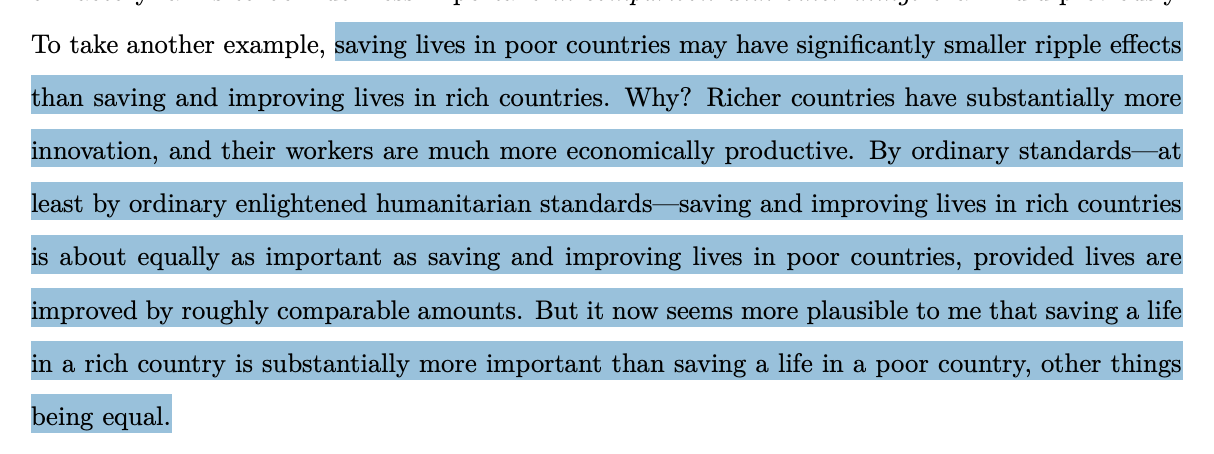

This is precisely why Nick Beckstead, a noted EA, argued in 2013 that, given the “overwhelming” moral importance of the far future — “millions, billions, and trillions” of years from now — we should prioritize saving the lives of people in rich countries over those in poor countries, other things being equal. The reason is that people in rich countries are better positioned to influence the far future.

This idea was named “longtermism” by William MacAskill in 2017. Before the word existed, the descriptor for those focused on the very far future was just “people interested in existential risk mitigation.” Hence, I was a longtermist before “longtermism” was part of our shared lexicon and the corresponding idea was incorporated into EA as one of its main “cause areas.” This is why I say that EA came to me, rather than me having discovered EA.

Yet, even in those early days, something seemed off about the community. It struck me as weirdly censorial, elitist, and hierarchical, even authoritarian in its structure — a fact that many later EAs picked up on, too.

I won’t go into a ton of details about my personal experiences in EA (of which there are many), though I will discuss some especially relevant incidents. Suffice it to say, for now, that I was repeatedly told not to write about certain topics; I was chastised for once publishing an article without the “approval” of an EA leader; I was told that if I continued to write about politics for outlets like Salon, I would lose opportunities for funding and collaboration; and after publishing a flurry of critiques beginning in the summer of 2022, once I had parted ways with EA, I was repeatedly harassed online and sent threats of physical violence (discussed more below). When I complained about this censorship, these intimidation tactics, and the EA community’s attempt to control its members, others began to speak out. For example, David Pearce, an EA, wrote:

Sadly, [Émile] Torres is correct to speak of EAs who have been “intimidated, silenced, or ‘canceled.’”

In 2019, I spent time at the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk (CSER) at Cambridge University. Over late-night drinks with CSER colleagues, I was surprised to hear many suggest that EA — our community — might be a “cult.” This stuck with me, and by the time I started to receive threats in late 2022 and 2023, it became obvious to me that they were right: EA really is a cult. What follows is an attempt to explain why I now think this.

A Huge Red Flag

EA advertises itself as being open to criticism. But this is a lie. EA likes the criticisms that it likes — those targeting specific components within its framework, requiring minor tweaks and adjustments. But if you criticize key aspects upon which the framework is based, you will be ostracized, attacked, and maybe even threatened with violence.

I discovered this first-hand, but I wasn’t the only one. In 2021, Carla Cremer and Luke Kemp coauthored an article titled, “Democratising Risk: In Search of a Methodology to Study Existential Risk.” It targeted the “techno-utopian approach” at the heart of EA-longtermism, arguing for a more democratic and pluralistic approach to studying existential risks. However, the authors encountered significant resistance from the EA community when soliciting feedback on the article. In a post on the Effective Altruism forum, Cremer recounted the difficulties like this (bold in original):

It could be a promising sign for epistemic health that the critiques of leading voices come from early career researchers within the community. Unfortunately, the creation of this paper has not signalled epistemic health. It has been the most emotionally draining paper we have ever written.

We lost sleep, time, friends, collaborators, and mentors because we disagreed on: whether this work should be published, whether potential EA funders would decide against funding us and the institutions we’re affiliated with, and whether the authors whose work we critique would be upset.

We believe that critique is vital to academic progress. Academics should never have to worry about future career prospects just because they might disagree with funders. We take the prominent authors whose work we discuss here to be adults interested in truth and positive impact. Those who believe that this paper is meant as an attack against those scholars have fundamentally misunderstood what this paper is about and what is at stake. The responsibility of finding the right approach to existential risk is overwhelming. This is not a game. Fucking it up could end really badly.

What you see here is version 28. We have had approximately 20 + reviewers, around half of which we sought out as scholars who would be sceptical of our arguments. …

The EA community prides itself on being able to invite and process criticism. However, warm welcome of criticism was certainly not our experience in writing this paper. …

We were told by some that our critique is invalid because the community is already very cognitively diverse and in fact welcomes criticism. They also told us that there is no TUA [techno-utopian approach], and if the approach does exist then it certainly isn’t dominant. It was these same people that then tried to prevent this paper from being published. They did so largely out of fear that publishing might offend key funders who are aligned with the TUA.

These individuals — often senior scholars within the field — told us in private that they were concerned that any critique of central figures in EA would result in an inability to secure funding from EA sources, such as OpenPhilanthropy. We don’t know if these concerns are warranted. Nonetheless, any field that operates under such a chilling effect is neither free nor fair. Having a handful of wealthy donors and their advisors dictate the evolution of an entire field is bad epistemics at best and corruption at worst.

The greatest predictor of how negatively a reviewer would react to the paper was their personal identification with EA.

The fact that the EA community can’t handle trenchant critiques of central pillars underlying its worldview should be a huge red flag. Again, it likes the criticisms it likes, so long as they concern minor, tweakable aspects of the general EA framework. If you target the framework itself, you’d better watch out.

Targeting the framework is exactly what Cremer and Kemp did, and it’s what my own critiques have aimed to achieve as well, which is why the three of us, independently, had quite negative experiences with EA.

Fear and Loathing Among the Altruists

When Cremer published this EA Forum post in 2021, I still didn’t consider EA to be a cult — only that it was cultish in certain ways, such as trying to censor dissent within the ranks of EAs, or silence critics from outside the community.

As noted, my opinion changed in late 2022, after I published a flurry of critiques of EA-longtermism in response to MacAskill’s 2022 book What We Owe the Future. This was just before the collapse of FTX, run by arguably the most famous EA-longtermist in the world: Sam Bankman-Fried. MacAskill went on a media blitz, and received a great deal of positive coverage. Much of what he said and wrote during this time rubbed me the wrong way, as I saw it as dishonest and misleading. It was, in my opinion, nothing more than propaganda for an ideology that I considered to be profoundly dangerous, for reasons outlined in my Aeon article from 2021. As one of the only former insiders who became publicly critical of EA, I felt a moral duty to speak out.

This is not to say that I was the only insider who was critical of EA. In fact, there are a lot of people in EA who think aspects of the community and ideology are rotten, but choose not to speak out. Instead, they engage in self-censorship. Why? Because they worry that speaking candidly about the movement’s problems will lead to them being ostracized, denied funding, and perhaps even harassed or threatened — exactly what Cremer highlights in her EA Forum post and I experienced in 2022 and 2023.

Consider another example: in early 2023, a group of around 10 EAs published a detailed critique of the anti-democratic and eugenic aspects of the community on the EA Forum. However, they posted this anonymously, precisely because they worried about retaliation. They wrote:

Experience indicates that it is likely many EAs will agree with significant proportions of what we say, but have not said as much publicly due to the significant risk doing so would pose to their careers, access to EA spaces, and likelihood of ever getting funded again.

Naturally the above considerations also apply to us: we are anonymous for a reason.

Someone on Twitter (I can’t recall who, or their exact words) responded to this: “I remember this stage of leaving a cult!” This person grew up in a Mormon community but eventually apostatized their faith, losing connections to their family in the process. In what kind of “intellectual” community do people feel the need to be anonymous when critiquing that community? That does not reflect well on the “epistemic health” of the movement, to quote Cremer.

To this day, I have no idea who those ~10 EAs were (maybe Cremer was one?), but someone whose name I won’t reveal wrote me just after it was posted on the EA Forum to say: “Please don’t promote this article on social media for another month or so. The authors are worried that if their article is linked to you in any way, the EA community will immediately dismiss it.” In other words, because I had become the leading critic of EA, any whiff of an association with me would be enough to render the entire critique “invalid.”

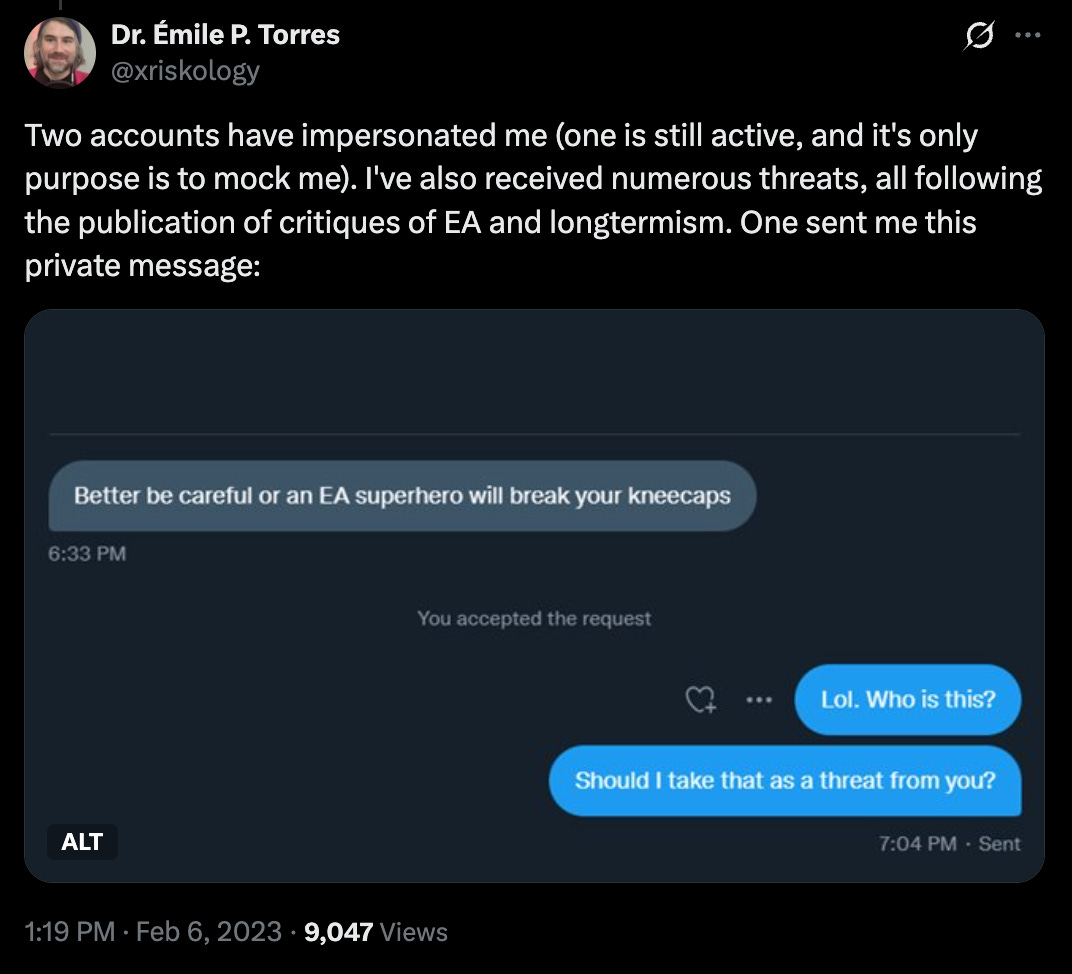

Almost immediately after I started publishing my critiques in 2022, I started to received threats of physical violence from the EA community. A large number of anonymous accounts on social media popped up for the sole purpose of harassing me and my friends. Some were banned by Twitter (before Musk took over) for bad behavior. Two accounts told me that an “EA superhero” would “kneecap” me, one of which later responded to me: “I wish you remained unborn 😭😭🙏🙏.”

An editor of mine, along with their boss and their boss’s boss, were harassed after I published an article about MacAskill’s book. Yet another editor was pressured into joining an hour-long (as I recall) Zoom meeting with EAs at one or more of the Oxbridge organizations because they wanted my article taken down. (My editor refused, because every claim made in that article was backed up by hyperlink citations.)

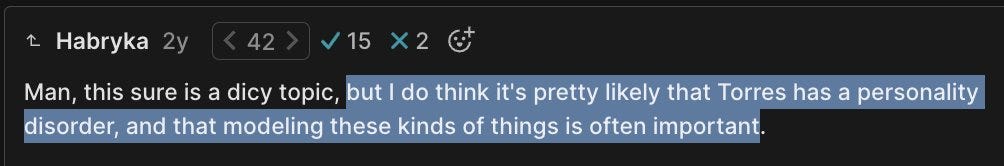

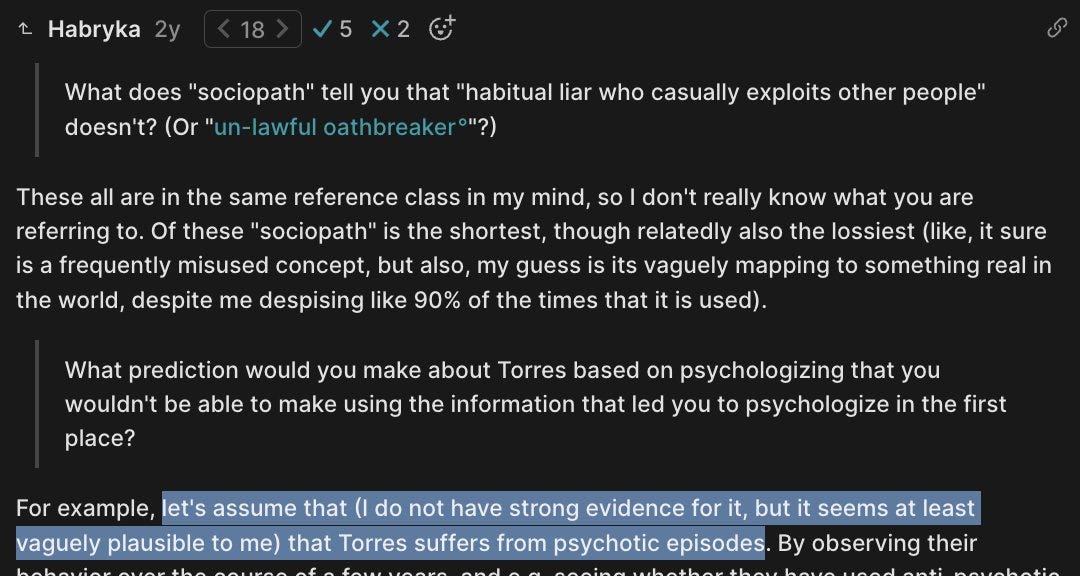

Some EAs wrote on the EA Forum that they think I must have a personality disorder, or that (I kid you not!) I have episodes of psychosis during which I write my critiques. Hence, if they can anticipate when I’m going to have a psychotic break with reality, they can better prepare for my articles.2

It’s as if they can’t fathom someone thinking the EA community is flawed without having some sort of neuropsychiatric abnormality. That is very cultish!

In fact, I became so frightened by the community, especially after the threats of violence, that I changed my route home at night while living in Germany. Not long after, I even received a death threat from an anonymous email account, along with two other anonymous emails, one calling me a “psycho” and the other threatening to dox me.

The Prophets of Rationality

It was at this point that I became convinced that EA probably is a cult. Others began to notice as well. In late-2022, EA Forum user “nadavb” published an article titled “EA May Look Like a Cult (And It’s Not Just Optics).” It begins with this description of the community:

What if I told you about a group of people calling themselves Effective Altruists (EAs) who wish to spread their movement to every corner of the world. Members of this movement spend a lot of money and energy on converting more people into their ideology (they call it community building). They tend to target young people, especially university students (and increasingly high school students). They give away free books written by their gurus and run fellowship programs. And they will gladly pay all the expenses for newcomers to travel and attend their events so that they can expose them to their ideas.

EAs are encouraged to consult the doctrine and other movement members about most major life decisions, including what to do for a living (career consultation), how to spend their money (donation advice), and what to do with their spare time (volunteering). After joining the movement, EAs are encouraged to give away 10% or more of their income to support the movement and its projects. It’s not uncommon for EAs to socialize and live mostly with other EAs (some will get subsidized EA housing). Some EAs want even their romantic partners to be members of the community.

While they tend to dismiss what’s considered common sense by normal mainstream society, EAs will easily embrace very weird-sounding ideas once endorsed by the movement and its leaders.

Many EAs believe that the world as we know it may soon come to an end and that humanity is under existential threat. They believe that most normal people are totally blind to the danger. EAs, on the other hand, have a special role in preventing the apocalypse, and only through incredible efforts can the world be saved. Many of these EAs describe their aspirations in utopian terms, declaring that an ideal world free of aging and death is waiting for us if we take the right actions. To save the world and navigate the future of humanity, EAs often talk about the need to influence governments and public opinion to match their beliefs.

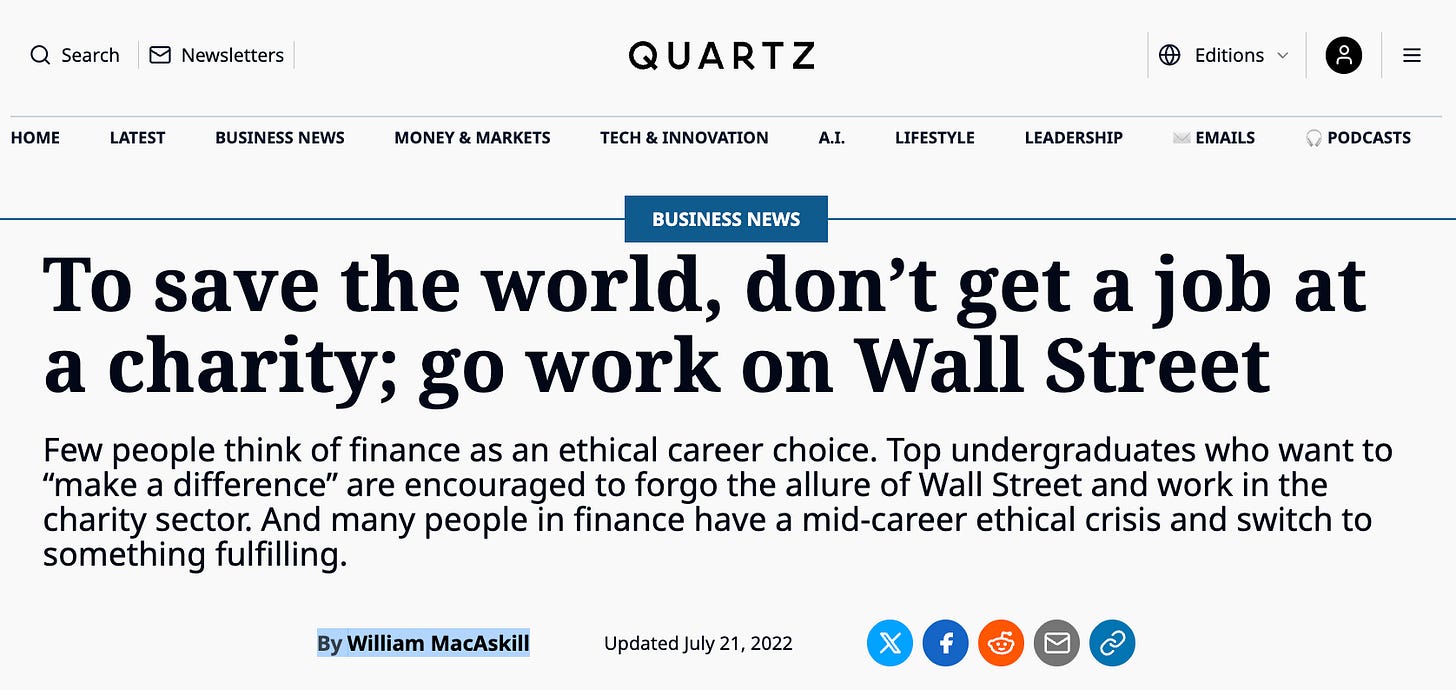

All of this is true. For example, according to the EA career-advice organization 80,000 Hours, among the top 10 “highest-impact career paths” is “helping build the effective altruism community” (!!). One way of doing this is by “earning to give,” whereby one pursues the most lucrative job possible to give more money to EA-approved charities and the EA community itself. This is precisely what MacAskill convinced Bankman-Fried to do in the early 2010s, which is why Bankman-Fried landed a job on Wall Street and then went into crypto. According to MacAskill, there is nothing morally wrong with working for what he calls “immoral organizations,” such as Wall Street firms and petrochemical companies — so long as one then donates one’s extra money toward “saving the world” (another phrase EAs use), you’ll be doing what’s right — even, what’s obligatory — from a utilitarian-esque perspective.

This is especially important given that we live in the “Time of Perils,” a period of heightened existential risk. EA-longtermists argue that this period may last for only a century or so, and that if we manage to squeeze through it, what awaits is a veritable “utopia” of personal immortality, endless cosmic delights, and literally “astronomical” amounts of value. We can build God-like superintelligence, reengineer humanity to become a new posthuman species, resurrect the dead who’ve been cryogenically frozen, and colonize the universe to create a heaven in the literal heavens full of 10^45 “digital people.”

This is the eschatology of the EA-longtermist cult, and it’s played an integral role in launching the ongoing race to build AGI, because — the reasoning goes — if we build a controllable superintelligence, then we get everything. With superintelligence, we’ll have a super-engineer, and since paradise is just an engineering problem — Bostrom literally calls it “paradise-engineering” — a techno-utopian world among the stars will immediately follow.

This is part of the doctrine — the dogma — of longtermism, as delivered by Prophets of Rationality like Bostrom, Ord, and MacAskill. And while EAs are open to soft criticisms of particular, tweakable features of this doctrine (as noted), they are very much not open to criticisms of the doctrine itself. That is precisely why I endured an avalanche of harassment and threats in response to my publications, and why the “ConcernedEAs” were afraid to publish their critique using their names.

Sexual Misconduct in EA

Even more, 2022 and 2023 saw a number of investigative pieces that revealed other cultish aspects of EA. Time magazine, for example, found rampant sexual misconduct within some EA groups. The article opens with the experiences of Keerthana Gopalakrishnan:

When the world started opening up from the COVID-19 pandemic, she moved to San Francisco and went to EA meetups, made friends with other EAs, and volunteered at EA conferences where they talked about how to use evidence and reason to do the most good in the world.

But as Gopalakrishnan got further into the movement, she realized that “the advertised reality of EA is very different from the actual reality of EA,” she says. She noticed that EA members in the Bay Area seemed to work together, live together, and sleep together, often in polyamorous sexual relationships with complex professional dynamics. Three times in one year, she says, men at informal EA gatherings tried to convince her to join these so-called “polycules.” When Gopalakrishnan said she wasn’t interested, she recalls, they would “shame” her or try to pressure her, casting monogamy as a lifestyle governed by jealousy, and polyamory as a more enlightened and rational approach.

After a particularly troubling incident of sexual harassment, Gopalakrishnan wrote a post on an online forum for EAs in Nov. 2022. While she declined to publicly describe details of the incident, she argued that EA’s culture was hostile toward women. “It puts your safety at risk,” she wrote, adding that most of the access to funding and opportunities within the movement was controlled by men. Gopalakrishnan was alarmed at some of the responses. One commenter wrote that her post was “bigoted” against polyamorous people. Another said it would “pollute the epistemic environment,” and argued it was “net-negative for solving the problem.”

Gopalakrishnan is one of seven women connected to effective altruism who tell TIME they experienced misconduct ranging from harassment and coercion to sexual assault within the community. The women allege EA itself is partly to blame. They say that effective altruism’s overwhelming maleness, its professional incestuousness, its subculture of polyamory and its overlap with tech-bro dominated “rationalist” groups have combined to create an environment in which sexual misconduct can be tolerated, excused, or rationalized away. Several described EA as having a “cult-like” dynamic.

It continues:

One recalled being “groomed” by a powerful man nearly twice her age who argued that “pedophilic relationships” were both perfectly natural and highly educational. Another told TIME a much older EA recruited her to join his polyamorous relationship while she was still in college. A third described an unsettling experience with an influential figure in EA whose role included picking out promising students and funneling them towards highly coveted jobs. After that leader arranged for her to be flown to the U.K. for a job interview, she recalls being surprised to discover that she was expected to stay in his home, not a hotel. When she arrived, she says, “he told me he needed to masturbate before seeing me.”

IQ Scores, Wytham Abbey, Doom Circles, a “Math Cult,” and Brainwashing

Just a few days before the Time article was published, Cremer — who was once an EA — wrote an article for Vox in which she revealed that CEA, the Centre for Effective Altruism, which shared office space with Bostrom’s FHI, had secretly tested an internal ranking system of EA members called “PELTIV.” Because the EA community is obsessed with IQ, people with IQs below 100 would have PELTIV points removed, while those with IQs above 120 would have them added.

Furthermore, it came to light — largely due to me having raised the issue on social media — that CEA’s umbrella organization, Effective Ventures, had secretly spent £15 million on an extravagant castle in Oxfordshire. This is, again, a community that preaches modest living, whereby members are encouraged to work extra hard and donate much of their disposable income to EA-approved charities, and to building the EA community itself. Yet they bought a “palatial estate” to host conferences. According to The New Yorker, the reasoning was that “the math could work out: it was a canny investment to spend [millions] of dollars to recruit the next Sam Bankman-Fried.”

It also turns out that MacAskill held a book release party at an “ultra-luxurious vegan restaurant where the tasting menu runs $438 per person with tip, before tax.” MacAskill — one of EA’s “charismatic” leaders — also intentionally spread favorable lies about the supposedly humble lifestyle of Bankman-Fried. In fact, Bankman-Fried flew in private jets and owned $400 million in Bahamian real estate.

Here’s yet another cultish aspect of EA: “Doom Circles,” which seem to have been most popular in the Bay Area. This involves “getting people in a circle to say what’s wrong with each other.” An EA Forum article from mid-2022 describes such events as follows:

The Doom Circle is an activity for a group of people, each of which has at least one thing they’re working on. The thing can be professional, personal, whatever. It can be as broad as simply existing well within a shared community, or as narrow as a specific project. Each person has a turn being the focus of the circle.

When it’s your turn as the focus of the circle, there’s first a disclaimer. It goes something like (to quote Ducan Sabien’s version):

We are gathered here this hour for the Doom of Steve. Steve is a human being who wishes to improve, to be the best possible version of himself, and he has asked us to help him “see the truth” more clearly, to offer perspective where we might be able to see things he does not. The things we have to say may be painful, but it is a pain in the service of a Greater Good. We offer our truths out of love and respect, hoping to see Steve achieve his goals, and he may take our gifts or leave them, as he sees fit.

Then everyone takes turns, as advertised, sharing whatever they think the focal person might fail at their efforts — called, in this case, their “doom”. Everyone has to participate, though offerings can be as short as 10 seconds or as long as 90. Nobody should go on for several minutes, though, and all critiques should be offered in good faith to help the focal person improve. The focal person can only say “thank you” to each doom.

After someone’s turn is complete there’s an outro. Again, to use Duncan’s version:

The Doom of Steve has come, and soon we will send it on its way. Like the calm after a storm, it is fitting that we hold the silence for a few minutes, in acknowledgement of what we’ve shared. Steve, thank you for hearing what we had to offer.

Two years later, in 2024, the clip below showed up on social media. Watch it to the end:

There is only one “math cult” that the audience members could be talking about: Effective Altruism. That same year (2024), someone published an article titled, “An interview with someone who left Effective Altruism,” in which EA is specifically described as a cult. Here are a few highlights, where “E” is the former EA and “C” is the interviewer:

E: And then at some point, there was kind of a conscious decision to shift our communication so that we weren’t mentioning EA or outwardly advertising that we were connected to the movement. I think that had to do with a lot of the scandal that was going on in the area at the time.

C: I see. And what was the scandal? Was it Sam Bankman-Fried stuff or other stuff?

E: Yeah, so SBF stuff but there was also a lot of weird like sexual harassment allegations and basically I think a lot, of a, lot men in particular in the EA had taken up polyamory, you know, were kind of avid arbiters of polyamory, they thought polyamory is the greatest thing ever and that’s still going on in EA. I And I think what ended up happening was there were a lot of these big conferences like EA Global, where people that are working at EA get together and there are lectures and you have a bunch of one-on-ones, and some people were going around in these conferences and trying to convince people to have threesomes with them, making women kind of uncomfortable in that way.

…

C: Yeah. That makes sense. Can I ask you to comment on a theory I have about effective altruism?

E: Sure.

C: And this is in part because I’ve been heavily involved in like thinking about AI policy with people in Washington and a lot of them have told me that, especially recently, there have been like embedded EA lobbyists who are like being offered to work for free because they’ve been paid by EA essentially on writing up bills and they I think of it as a kind of intentional effort for Silicon Valley to distract policymaking on AI away from short-term problems, and I will just add that the folks that I’ve talked to who are interested in EA or maybe even part of EA, I don’t think they’re intentionally doing that. I kind of feel like there’s a way that young people are being taken advantage of, because these are young people, early 20s, maybe mid-20s typically, that they’re like the true believers and they are going to Washington and they want to do good, but I feel that the actual goal the overall movement is to not do anything. Does that make sense to you?

E: Yeah, it totally does. I think that longtermism is just an excuse for a bunch of guys to legitimize the fun philosophical questions that they think are really interesting, by making it into thinking through a catastrophic event, that would have an insane effect on the world and the future and therefore it’s like the only thing that we should focus on, but actually just because it is really fun to think about that. Yeah. And so I totally see that that’s part of what’s going on and I think my experience in a really scary way is that there’s been a total shift in the last maybe three or four years away from tangible short-term issues, whether it comes to AI or global health development or animal advocacy, where we’re actually trying to make policy changes and effect changes and support interventions in the here and now, like helping human beings and helping animals that live on this earth now.

So there’s been a real shift away from that and towards talking about, you know, people that are going to be living 100, 200, 300 years from now, or even thousands of years from now [a reference to longtermism], where it’s this like probability game of, we have no way of knowing what life is going to be like, you know, 100, 200, 300, 1000 years from now, but it’s like a slim chance that AI takes over the world and tries to kill everyone, then working on AI safety is the most important thing that anyone could spend their time doing. And for some reason, I think EA thinks that means everyone should quit their job and work full-time on AI safety and alignment which means that logic doesn’t make a ton of sense.

…

E: Yeah, well I think that EA is something that is growing and growing, and kind of wants everyone to join, they’re very intentional about that, like they are very, very strategic about how we get as many people involved as possible. And it is kind of scary when you look at it. So part of my work at One with the World was helping students think about how they could engage more students on their campus and get them to show up to events and clubs. And so I would do a lot of research into what the Center for Effective Altruism was advising their student leaders to do to get people to come to events and to join their mentorship program. And it is kind of terrifying how intensely strategic they were when we’re talking about 19-year-old students trying to figure out the best way to trick other 19-year-old students into coming, you know, it’s like being brainwashed and coming to this event, and then joining the mentorship program and blah, blah blah. And they’re sometimes very effective at it.

…

C: It’s a weird cult in the sense of like, why AI? But when you put it together like you did with here’s how you should eat, here is what you work on, here how you should think, here’s what you shouldn’t think about, and then there’s like that intense recruitment and it’s not just like, try this out, it’s a lifelong commitment. It really adds up to something kind of spooky.

E: It does, yeah. And again, I think that there are incredible people that are involved with EA, but I sometimes think it is possible to pick out parts of EA that are really good and helpful and smart without buying into other parts of it. And I think that’s easier for adults who have come into it later in life, and harder for people who enter the movement as students and are kind of brainwashed from the get-go to zoom out and see it that way.

A Checklist of Culty Characteristics

I don’t know much about a website called “Cult Recovery 101” (seems legit), but it includes a useful list of characteristics of a cult. Let’s take a look at these characteristics (quoted in bold as bullet points), commenting on each in turn:

The group is focused on a living leader to whom members seem to display excessively zealous, unquestioning commitment.

There is a lot of hero-worship within EA. This was a main point of yet another EA Forum post by Cremer, bemoaning the worship of IQ.3 People like MacAskill, Bostrom, and Yudkowsky are elevated to an almost messianic level of cosmic importance. They are the prophets of EA-longtermism, sent by the Rationality Gods to deliver fundamental truths about the apocalyptic hazards and utopian promises that lie ahead.

The group is preoccupied with bringing in new members.

EAs spend a great deal of resources trying to convert students on elite university campuses to the cause, because they think these students are most likely to become successful. They even now target high school kids. As noted, the 80,000 Hours website lists “Helping build the effective altruism community” as one of its top 10 “highest-impact career paths our research has identified so far.”

The group is preoccupied with making money.

Absolutely! Earning to give is a good example of this, where the goal is to create home-grown millionaires or billionaires who can funnel their money back into EA for “community building.” But EA has also worked hard to develop relationships with rich and powerful people. MacAskill — unbeknownst to nearly everyone else in the EA community — exchanged personal messages with Elon Musk in an effort to get Musk to buy Twitter with Bankman-Fried (lolz). In fact, one journalist described Bankman-Fried’s mission as “to get filthy rich, for charity’s sake.” Which “charities”? Those specifically approved by EA organizations, as well as Bankman-Fried’s own FTX Future Fund, run by Nick Beckstead (mentioned above), which funded longtermist research projects focused on things like “how to build a superintelligent God that brings about utopia rather than annihilating us.”

EAs are also explicit that their goal is to acquire a large fraction of the world’s wealth. Why? Because many of them truly believe in the “moral” mission of EA, and the more wealth and power they acquire, the better positioned they’ll be to shape the world today along with the future direction of civilizational development. As I noted in an article for Salon:

Yet another article [written by EAs] addresses the question of whether longtermists should use the money they currently have to convert people to the movement right now, or instead invest this money so they have more of it to spend later on.

It seems plausible, the author writes, that “maximizing the fraction of the world’s population that’s aligned with longtermist values is comparably important to maximizing the fraction of the world’s wealth controlled by longtermists,” and that “a substantial fraction of the world population can become susceptible to longtermism only via slow diffusion from other longtermists, and cannot be converted through money.” If both are true, then

we may want to invest only if we think our future money can be efficiently spent creating new longtermists. If we believe that spending can produce longtermists now, but won’t do so in the future, then we should instead be spending to produce more longtermists now instead.

Such talk of transferring the world’s wealth into the hands of longtermists, of making people more “susceptible” to longtermist ideology, sounds — I think most people would concur — somewhat slimy. But these are the conversations one finds on the EA Forum, between EAs.

Money, wealth, power. A castle in Oxfordshire. Private jets and hundreds of millions of dollars in Bahamian real estate. $400 per plate restaurants to celebrate a book launch. Fostering relationships with deranged billionaires. EA looks a lot like Scientology.

Questioning, doubt, and dissent are discouraged or even punished.

We saw many examples of this above: Cremer and Kemp, the ConcernedEAs, and my own experiences. Worse, true believers in the EA dogma can be quite scary in how they deal with dissent. Not to belabor the point, but here’s something I wrote in a Truthdig article from 2023 about Simon Knutsson, an EA-turned-critic:

I’m not the only one who’s been frightened by the TESCREAL community. Another critic of longtermism, Simon Knutsson, wrote in 2019 that he had become concerned about his safety, adding that he’s “most concerned about someone who finds it extremely important that there will be vast amounts of positive value in the future and who believes I stand in the way of that,” a reference to the TESCREAL vision of astronomical future value. He continues:

Among some in EA and existential risk circles, my impression is that there is an unusual tendency to think that killing and violence can be morally right in various situations, and the people I have met and the statements I have seen in these circles appearing to be reasons for concern are more of a principled, dedicated, goal-oriented, chilling, analytical kind.

Knutsson then remarks that “if I would do even more serious background research and start acting like some investigative journalist, that would perhaps increase the risk.” This stands out to me because I have done some investigative journalism. In addition to being noisy about the dangers of TESCREALism, I was the one who stumbled upon Bostrom’s email from 1996 in which he declared that “Blacks are more stupid than whites” and then used the N-word. This email, along with Bostrom’s “apology” — described by some as a flagrant “non-apology” — received attention from international media outlets.

Mind-numbing techniques (such as meditation, chanting, speaking in tongues, denunciation sessions, debilitating work routines) are used to suppress doubts about the group and its leader(s).

Doom Circles! Threats of ostracization and losing opportunities for funding and collaboration! Etc.

The leadership dictates sometimes in great detail how members should think, act, and feel (for example: members must get permission from leaders to date, change jobs, get married; leaders may prescribe what types of clothes to wear, where to live, how to discipline children, and so forth).

Once again, copious examples were provided above. CEA even published a guide for “responding to journalists,” which basically outlines what EAs should and shouldn’t say to journalists about the community. Community members also “flag” articles critical of EA (I’m sure this one will be added to the list). As I showed in a Salon article, there’s a huge emphasis within EA on PR and marketing (again, not unlike Scientology). EAs are even encouraged to act in specific ways so as not to weird people out. Here’s what I wrote about this:

To quote another EA longtermist at the Future of Humanity Institute:

Getting movement growth right is extremely important for effective altruism. Which activities to pursue should perhaps be governed even more by their effects on movement growth than by their direct effects. … Increasing awareness of the movement is important, but increasing positive inclination is at least comparably important.

Thus, EAs — and, by implication, longtermists — should in general “strive to take acts which are seen as good by societal standards as well as for the movement,” and “avoid hostility or needless controversy.” It is also important, the author notes, to “reach good communicators and thought leaders early and get them onside” with EA, as this “increases the chance that when someone first hears about us, it is from a source which is positive, high-status, and eloquent.” Furthermore, EAs

should probably avoid moralizing where possible, or doing anything else that might accidentally turn people off. The goal should be to present ourselves as something society obviously regards as good, so we should generally conform to social norms.

In other words, by persuading high-status, “eloquent” individuals to promote EA and by presenting itself in a manner likely to be approved and accepted by the larger society, the movement will have a better chance of converting others to the cause.

I’m reminded here of another passage from Knutsson, which goes:

Like politicians, one cannot simply and naively assume that these people [EAs] are being honest about their views, wishes, and what they would do. In the Effective Altruism and existential risk areas, some people seem super-strategic and willing to say whatever will achieve their goals, regardless of whether they believe the claims they make — even more so than in my experience of party politics.

The group is elitist, claiming a special, exalted status for itself, its leader(s), and members (for example: the leader is considered the Messiah or an avatar; the group and/or the leader has a special mission to save humanity).

100% — the goal of EA is to “save the world,” and the structure of its community is extremely elitist. There’s a very strong element of messianism, whereby EAs see themselves as “superior” to others and tasked to save the world. As Time writes:

The movement’s high-minded goals can create a moral shield, they say, allowing members to present themselves as altruists committed to saving humanity regardless of how they treat the people around them. “It’s this white knight savior complex,” says Sonia Joseph, a former EA who has since moved away from the movement partially because of its treatment of women. “Like: we are better than others because we are more rational or more reasonable or more thoughtful.” The movement “has a veneer of very logical, rigorous do-gooderism,” she continues. “But it’s misogyny encoded into math.”

I’m reminded of a quote from Giego Caleiro, an EA who was (as I understand it) kicked out of some EA groups for manipulative and dishonest behavior:

Back when I was leaving Oxford, right before Nick [Bostrom] finished writing Superintelligence, in my last day right after taking our picture together, I thanked Nick Böstrom on behalf of the 10^52 people [one estimate of how many future digital people there could be] who will never have a voice to thank him for all he has done for the world. Before I turned back and left, Nick, who has knack [sic] for humour, made a gesture like Atlas, holding the world above his shoulders, and quasi letting the world fall, then readjusting. While funny, I also understood the obvious connotation of how tough it must be to carry the weight of the world like that.

Yes, poor Bostrom, carrying the weight of the world on his shoulders!

The group has a polarized us-versus-them mentality, which causes conflict with the wider society.

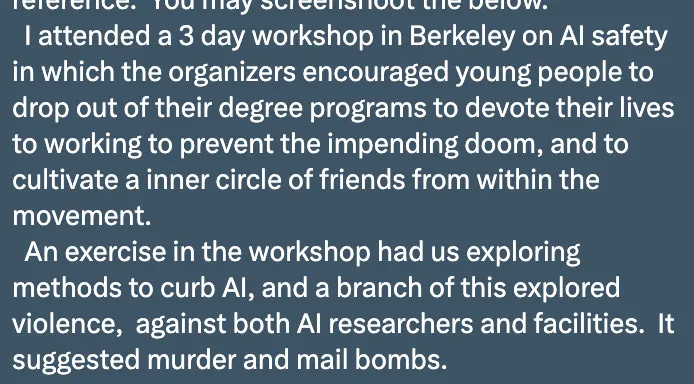

EA definitely has an in-group/out-group mentality. Furthermore, many really do believe that we’re on the verge of total annihilation because we don’t know how to control superintelligence. I have worried repeatedly about this resulting in conflict and violence, and my considered view is that it’s only a matter of time before someone in the EA (or Rationalist) communities takes matters into their own hands and, motivated by the “apocalyptic mindset” of EA-longtermist eschatology, does something terrible. As someone (who I won’t name) wrote me after I shared on social media that I’d received threats of violence from the community:

Those remarks? I quote them here:

Under the heading “produce aligned AI before unaligned [AI] kills everyone,” the meeting minutes indicate that someone suggested the following: “Solution: be Ted Kaczynski.” Later on, someone proposed the “strategy” of “start building bombs from your cabin in Montana,” where Kaczynski conducted his campaign of domestic terrorism, “and mail them to DeepMind and OpenAI lol.” This was followed a few sentences later by, “Strategy: We kill all AI researchers.”

Yikes. This is a ticking time bomb.

The group’s leader is not accountable to any authorities (as are, for example, military commanders and ministers, priests, monks, and rabbis of mainstream denominations).

The community protects its own. There’s a whisper network surrounding one of the leading EAs. And there’s this excerpt from the aforementioned Time article about sexual misconduct:

Several women say that the way their allegations were received by the broader EA community was as upsetting as the original misconduct itself. “The playbook of these EAs is to discourage victims to seek any form of objective, third-party justice possible,” says Rochelle Shen, who ran an EA-adjacent event space in the Bay Area and says she has firsthand experience of the ways the movement dismisses allegations. “They want to keep it all in the family.”

The group teaches or implies that its supposedly exalted ends justify means that members would have considered unethical before joining the group (for example: collecting money for bogus charities).

EA has been hugely influenced by utilitarianism, which essentially says the ends justify the means. This is why Bankman-Fried felt “justified” in committing massive fraud for the greater cosmic good, and why Beckstead argues that we shouldn’t prioritize saving the lives of people in poor countries, other things being equal. In his 2002 article introducing the existential risk concept, Bostrom claims that we should use preemptive violence to obviate scenarios that might destroy a posthuman utopia. In 2019, he argued that we should seriously consider implementing mass, invasive, global surveillance to prevent “civilisational devastation” (i.e., an existential catastrophe). Most people, before joining EA and becoming a longtermist, would have likely said that these sorts of things are unethical. But within the longtermist framework, nothing really matters except for “protecting” and “preserving” what Toby Ord calls our “vast and glorious” future.

No doubt many EAs would have also said it’s unethical to work for Wall Street firms, petrochemical companies, and other “immoral organizations.” Yet some went on to pursue the earn-to-give career path, such as Bankman-Fried, taking high-paying jobs at harmful companies to donate more to EA-approved charities.

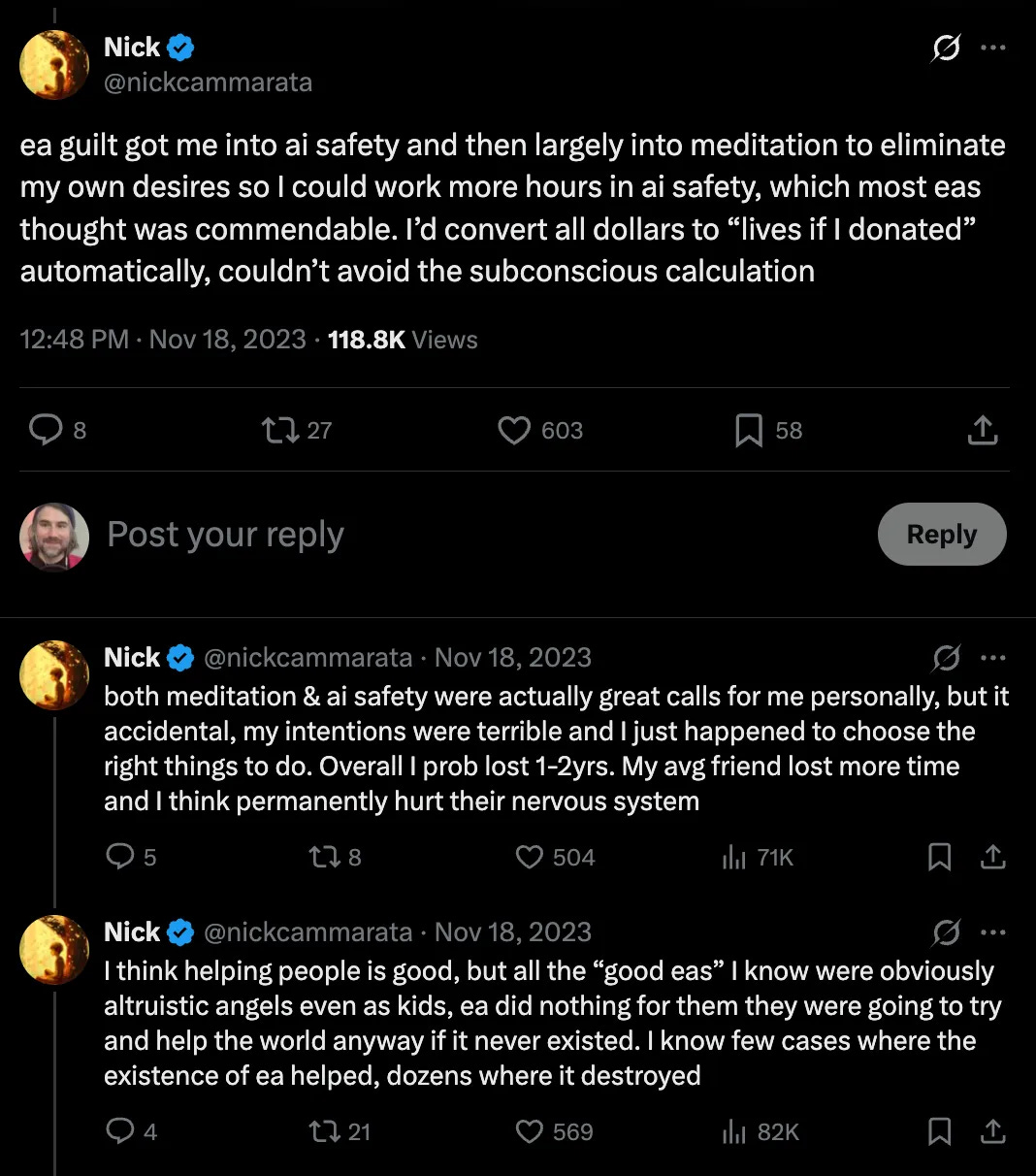

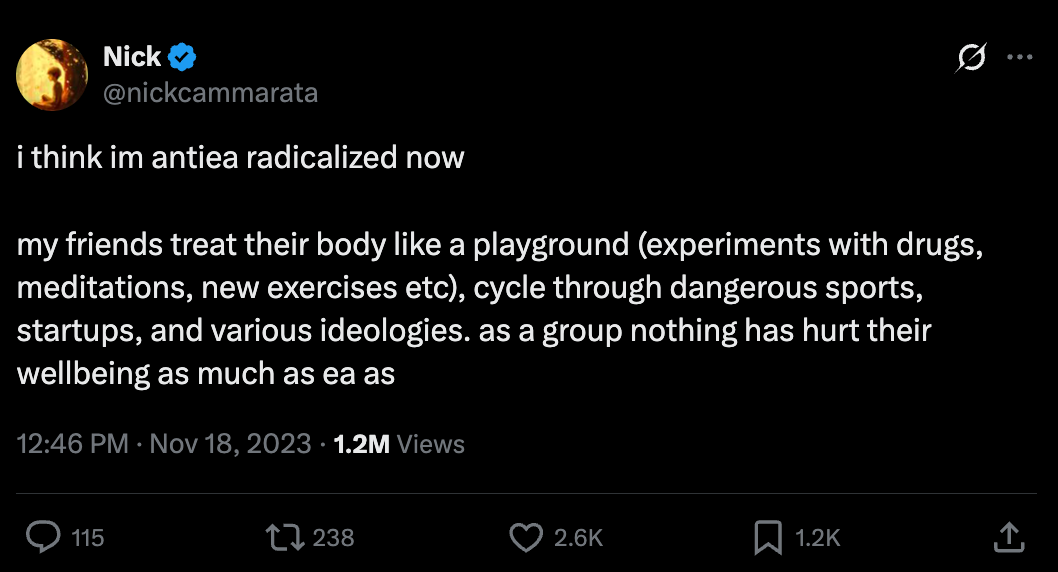

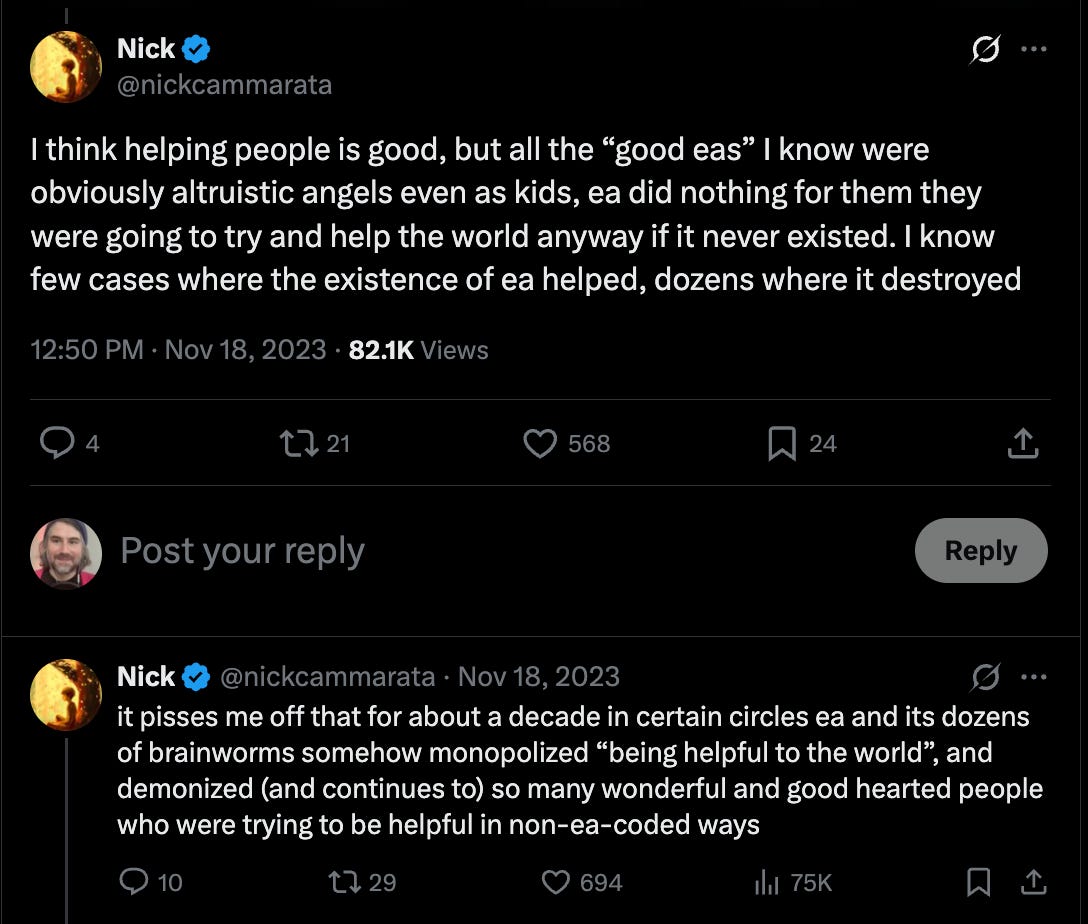

The leadership induces guilt feelings in members in order to control them.

Consider this thread from someone who worked for OpenAI for 5 years and used to be an EA:

He begins the thread with the following:

Members’ subservience to the group causes them to cut ties with family and friends, and to give up personal goals and activities that were of interest before joining the group.

EA encourages people not to pursue their passions, but instead to take careers that 80,000 Hours considers to be “high impact,” such as promoting the EA movement. (Continued below …) Incidentally, a family member of one of the leading EAs contacted me a year or two ago (being intentionally vague) to tell me that they’re worried their relative had joined a cult. I didn’t have much to say to them except, “Yeah, it is concerning.”

Members are encouraged or required to live and/or socialize only with other group members.

Recall the quote from “nadavb” above:

It’s not uncommon for EAs to socialize and live mostly with other EAs (some will get subsidized EA housing). Some EAs want even their romantic partners to be members of the community.

Conclusion

In my opinion, EA is quite clearly a cult. I do not say this as a fact — there is no fact of the matter — but as a well-informed opinion based on my experiences in the community and those of other people, along with undisputed facts about the way EA operates. Be wary of this movement, and know that you don’t have to be an EA to be committed to improving the world as much as possible. I’ve repeatedly said that once I have a stable job that earns over $40k a year, I will donate everything above that threshold to charity (mostly to grassroots organizations in the Global South, such as this one). Yet I have a very negative view of EA — its ideology and community — and want nothing to do with it.

This leads me to a final thought: has EA done more good or harm in the world? Folks like MacAskill love to talk about “counterfactuals” — this is a key part of his argument for earning to give: if you, an “altruist,” don’t take the job opening at an “immoral organization,” someone else, a “non-altruist,” will. So it might as well be you who takes the job (a conclusion that completely ignores the issue of moral integrity).

But they never talk about counterfactuals when bragging about how much “good” the EA movement has done in the world. That is to say, they never consider how much “good” would have been done if EA had never existed. As the former EA and OpenAI employee quoted above writes:

My guess is that if EA had never existed, the world would actually be a better place. Why? Because most EAs would still have given their money to charity, non-EAs would not have been “demonized” as “ineffective” altruists, and a much wider range of charities — such as grassroots organizations in the Global South — might have been funded. Put differently, most of these people don’t give to charity because they got into EA, they got into EA because they give to charity. Hence, if EA had never existed, the world could very well have benefitted more.

As I explain in this article for Truthdig, EA is actually far worse than traditional philanthropy for grassroots organizations, which has left many people in the Global South feeling even more hopeless than before. You might also check out the excellent book The Good It Promises, The Harm It Does for additional accounts of how EA has destroyed philanthropic endeavors, essentially making things much worse for those who aren’t in the cult of EA but want to help others as much as possible.

What do you think? What have I overlooked? How might I be wrong? Thanks for reading to the end of this long article! As always:

Thanks for reading and I’ll see you on the other side.

Thanks to Remmelt Ellen for insightful comments on an earlier draft. You can follow Remmelt on X at: @RemmeltE.The TESCREAL movement even gave us the terms “artificial general intelligence” (AGI) and “artificial superintelligence” (ASI).

I do not have a personality disorder, nor have I ever experienced an episode of psychosis. You know, for the record! Lol.

To quote her at length:

As it becomes more evident what type of person is considered value-aligned a natural self-selection will take place. Those who seek strong community identity, who think the same thoughts, like the same blogs, enjoy the same hobbies… will identify more strongly, they will blend in, reinforce norms and apply to jobs. Norms, clothing, jargon, diets and a life-style will naturally emerge to turn the group into a recognisable community. It will appear to outsiders that there is one way to be EA and that not everyone fits in. Those who feel ill-fitted, will leave or never join.

The group is considered epistemically trustworthy, to have above average IQ and training in rationality. This, for many, justifies the view that EAs can often be epistemically superior to experts. A sense of intellectual superiority allows EAs to dismiss critics or to only engage selectively. A homogenous and time-demanding media diet — composed of EA blogs, forum posts and long podcasts — reduces contact hours with other worldviews. When in doubt, a deference to others inside EA, is considered humble, rational and wise. …

EA is reliant on feedback to stay on course towards its goal. Value-alignment fosters cognitive homogeneity, resulting in an increasing accumulation of people who agree to epistemic insularity, intellectual superiority and an unverified hierarchy. Leaders on top of the hierarchy rarely receive internal criticism and the leaders continue to select grant recipients and applicants according to an increasingly narrow definition of value-alignment. A sense of intellectual superiority insulates the group from external critics. This deteriorates the necessary feedback mechanisms and makes it likely that Effective Altruism will, in the longterm, make uncorrected mistakes, be ineffective and perhaps not even altruistic. …

EAs give high credence to non-expert investigations written by their peers, they rarely publish in peer-review journals and become increasingly dismissive of academia, show an increasingly certain and judgmental stance towards projects they deem ineffective, defer to EA leaders as epistemic superiors without verifying the leaders epistemic superiority, trust that secret google documents which are circulated between leaders contain the information that justifies EA’s priorities and talent allocation, let central institutions recommend where to donate and follow advice to donate to central EA organisations, let individuals move from a donating institution to a recipient institution and visa versa, strategically channel EAs into the US government, adjust probability assessments of extreme events to include extreme predictions because they were predictions by other members.

It’s worth reading her article in full.

My baseline for any group is — how smug are its members? All the rest of this typical crap follows.

Good work, by the way!

Isn't it so sad that similar controlling and "religious" impulses continue to recur throughout human history.

Any idea no matter how positive can be used by those that want to control others.

I always had a problem with this group as I am a Bayesian statistician and they have both very strong prior beliefs and model uncertainty.

My meta philosophy of being clear with my biases and trying to test ideas with evidence strongly biases me away from such "Napoleonic plans". Your assumptions about AI and humanity are just so unlikely to be true. Which leads me back to I think a similar position as the author and maybe like the Gates foundation. Lets focus on tractible things like education of women and curing malaria (my PhD was in malaria control modelling). All the while keeping an eye on big developments and being as open, rational and transparent as possible with our own ideas.