On the Copernican, Darwinian, and Shelleyan Revolutions in Thinking About Humanity and Our Place in the Universe

In a recent article for Aeon, the historian Thomas Moynihan writes this about our realization that humanity can go extinct:

It’s now clear humanity lacks the luxury of eternity. We know this because evidence has accumulated to show that there are greater, even more encompassing mortalities than our own. We now understand Earth and its life had their origins and, one day, they will be cremated by our ageing Sun. A ‘third death’, then. Beyond that, even the Universe itself has its bounds: it began with a bang, and the consensus view is that, in the distant future, it will likely have its end. Thus, a ‘fourth death’. Multiple grander mortalities, expanding concentrically outward.

We are only just coming to terms with this – this supremacy of finitude. It marks a historic reorganisation of our sense of orientation that may, one day, be judged comparable to that of the Copernican Revolution. Just under 500 years ago, Nicolaus Copernicus initiated a string of discoveries eventually proving our planet is not the centre of a tidy, manageable cosmos. Instead, Earth pirouettes around a mediocre star within an ungraspably vast Universe. It took generations for people to start noticing – and giving names to – what Copernicus had wrought. Similarly, we are only now waking up to the significance of the nested mortalities we live within. With the most seismic revolutions, it takes time for the dust to settle before we can glimpse the landscape transformed.

This touches upon an idea that I’ve been discussing since 2022—one that I chose not to include in my book Human Extinction: A History of the Science and Ethics of Annihilation, as I wanted to publish it as a stand-alone paper. Since I haven’t had time to do this, I’ll outline the idea here:

Historians of science note that we have undergone two or three profound “revolutions” in our understanding of the nature of humanity and our place within the cosmos. The first is the Copernican revolution: this demolished the previously widespread view (going back at least to Aristotle) that Earth is located at the very center of the universe. Rather than the sun revolving around the earth, Copernicus argued that the earth revolves around the sun. The “fixed stars” in the sky—the stars that we see in the same place every night throughout the year—correspond to their own solar systems, with planets like Earth revolving around them. This was a shocking realization: we do not, it turns out, occupy a special place in the universe. Our planet is but one speck of dust orbiting a flame among innumerable other specks and flames.

But even if we aren’t special cosmically, we could still take comfort in the idea that our species is the pinnacle of creation. In particular, there exists a fundamental ontological gap between us and the rest of the Animal Kingdom, as we possess immortal souls, whereas other creatures do not. We are different in kind rather than degree from the rest of God’s marvelous creation, and this makes us special, unique, and in some sense superior.

Three centuries after Copernicus published On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, which initiated the revolution that bears his name, Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species. Whereas the Copernican revolution took more than a century to unfold, the Darwinian revolution was almost immediate: Darwin proved beyond a reasonable doubt that we are, in fact, different from other creatures by degree rather than kind. There is no ontological gap separating us and them, as our species evolve piecemeal from “lower” beings that no one would argue had souls, and we are not the pinnacle of evolution because the evolutionary process is a-teleological.

This was the second great injury to the narcissism of our species: whereas Copernicus removed us from the center of the universe, the Darwinian revolution dethroned us from the center of the biological world.

The third major shift in our understanding of humanity and our place in the universe was the Freudian revolution. Unlike the previous two, this one is far more controversial, as many historians argue that Freud’s views weren’t scientific—but merely pseudoscientific. (The essence of this revolution was the idea that “we” are not really in control of our psychological faculties: the subconscious is.) Given that the status of Freud’s theories as science are so controversial, I will ignore this “revolution” here, focusing instead on the Copernican and Darwinian revolutions.

Both of these revolutions were assaults on our default tendency toward anthropocentrism, the idea that we—our species—stands at the center of everything. The Copernican revolution destroyed a cosmological interpretation of anthropocentrism, while the Darwinian revolution destroyed a biological interpretation.

My contention since 2022 has been that historians have thus far failed to notice a third version of anthropocentrism that survived the obliteration of the first two versions: the idea that, even if we aren’t the center of the universe or the biological world, we are nonetheless a permanent fixture within the cosmos. That is to say, it simply can’t be that the universe could exist without us. The science fiction author HG Wells articulated this idea in his 1893 essay “The Extinction of Man”1:

It is part of the excessive egotism of the human animal that the bare idea of its extinction seems incredible to it. “A world without us!” it says, as a heady young Cephalaspis might have said it in the old Silurian sea. But since the Cephalaspis and the Coccostëus many a fine animal has increased and multiplied upon the earth, lorded it over land or sea without a rival, and passed at last into the night. Surely it is not so unreasonable to ask why man should be an exception to the rule. From the scientific standpoint at least any reason for such exception is hard to find.

As I show in Human Extinction, the idea of human extinction dates back to the Presocratic philosophers—e.g., Xenophanes and Empedocles.2 Curiously, though, while both argued that human extinction is inevitable in the future (due to the fundamental temporal structure of our cyclical cosmos), our species will always reappear after dying out. In other words, they accepted a kind of human extinction, whereby our species will disappear entirely from the universe, yet also insisted that this is only ever a temporary state of affairs. We are thus indestructible in a deeper sense, an idea that channels the third version of anthropocentrism mentioned above.

It wasn’t until the 19th century that intellectuals in the Western tradition began to take seriously the idea that we might disappear both entirely and forever. The 19th century was thus the onset of this new revolution, which stemmed not from the work of this or that particular individual—as in the eponymous Copernican and Darwinian revolutions—but from a gradual chipping away of dominant ideologies and worldviews that reigned from the 4th or 5th centuries CE until the early, mid-, and especially late 1800s. These are: (1) the Great Chain of Being—especially the principle of plenitude enfolded within this model of reality—and (2) Christianity—especially its ontological claim that humanity is unique and its eschatological claim that our extinction is impossible because it does not fit with God’s prewritten plan for humanity and the universe.

Because this third revolution—again, I am ignoring the Freudian revolution—was not the product of any particular individual(s), but rather the result of many different people in different fields of study, it has not been as easy to recognize. But I would argue that it is no less profound than the other two revolutions: we are not even special as actors in the cosmic drama unfolding around us. The universe does not care if we exist or not; we could meet the same fate as the Dodo and dinosaurs, and the universe would simply move on. This is yet another catastrophic injury to the narcissism of our species, to the default anthropocentrism that we believe because we desire to believe that we are somehow special. We aren’t.

Like the Copernican revolution, this third revolution has unfolded rather slowly. Though we needn’t go into all the details here—see Part I of Human Extinction for a comprehensive exploration of the relevant history—the middle of the 19th century witnessed a sudden, significant shift in our thinking about human extinction: the discovery of the second law of thermodynamics in the early 1850s led many scientists to immediately see that our extinction is not only possible but inevitable in the long run (a “double trauma,” as I say in the book). About 100 years later, the Castle Bravo debacle in the Marshall Islands forced us to realize that human extinction could happen in the very near future, due not to entropy but human foolishness paired with unprecedentedly powerful technologies. In Human Extinction, I identify two other moments in recent history—the early 1990s, and (not long after) the turn of the century—as pushing this third great revolution forward.

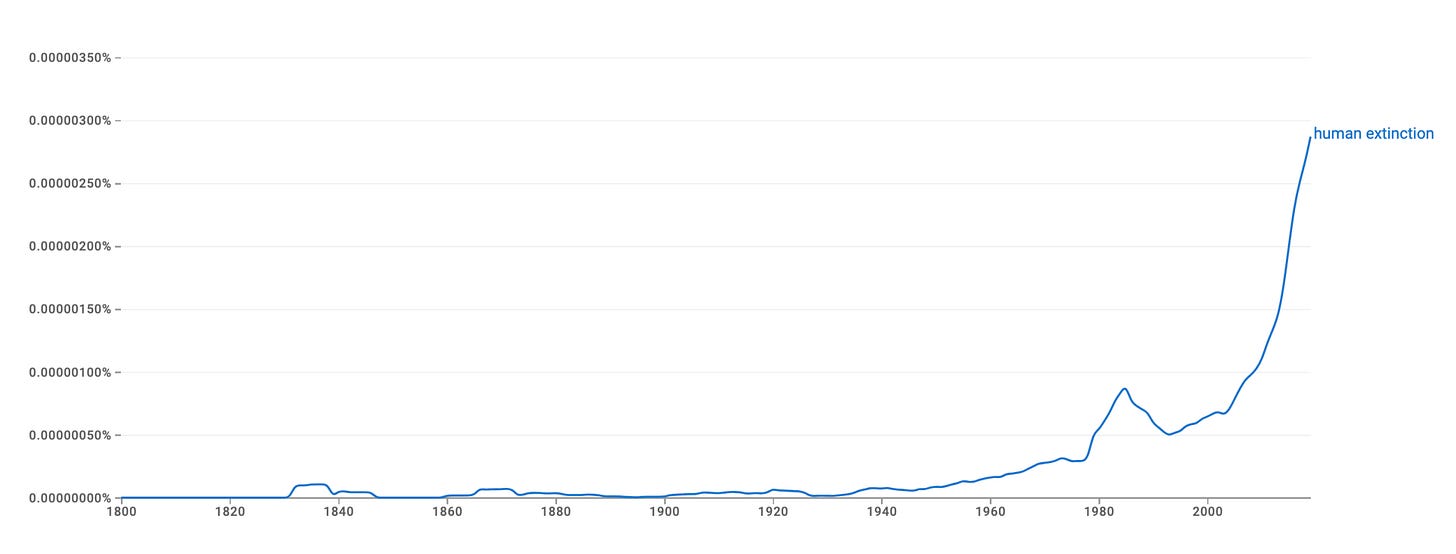

A search of the Google Ngram Viewer shows results that fits well with my periodization of thinking about human extinction in the West over time. As you can see, never before has the idea of human extinction been referenced more than it is today:

This is an extraordinary fact. Unlike the Copernican and Darwinian revolutions, this third revolution is still ongoing. It is happening in realtime, as more and more people come to recognize that we are not, in fact, a permanent fixture of the universe: it is entirely possible that our species disappears entirely and forever, perhaps in the near future; we are not indestructible, as even early pioneers of extinction thinking like Xenophanes and Empedocles thought.

And there is no guarantee that this revolution will unfold to completion, as a crucial “enabling condition” (as I call it in the book) for acknowledging the precarity of our collective existence is a secular outlook. If religion were to make a come-back in the Western world, which is possible, then the ontological and eschatological components of Christianity (or other Judeo-Christian religious belief systems) would effectively “block” the idea of human extinction, thus rendering it once again unthinkable—a literal oxymoron, since contained within the concept of humanity is the concept of immortality.

Let’s call this third revolution the “Shelleyan revolution,” after Mary Shelley, who was among the very first to write about human extinction, as we currently understand it, in her novel The Last Man.

In sum, my contention is that historians have missed a third great revolution in thinking about the nature of humanity and our place in the cosmos. The Copernican revolution removed us from the center of the universe, thus mortally wounding a particular interpretation of anthropocentrism. The Darwinian revolution demolished a different interpretation of anthropocentrism by dethroning us from the center of the biological world. Yet there is another version of anthropocentrism that remained: the idea that we are indestructible features of the universe; that even if we aren’t special in other ways, we are at least special in that the universe, so to speak, needs us.

The third revolution—the Shelleyan revolution, for lack of a better term—is dissolving this last remaining sense of our specialness in the cosmos. We are vulnerable to extinction just like any other species, and if we were to disappear the universe would go on as if nothing had happened.

The publication date for this comes from Burd, Gene. “The Time Machine: An Invention by HG Wells (1895).” Utopian Studies 12, no. 2 (2001): 371–73.

As well as the ancient atomists and Stoics. See my book for details.

I imagine would could also point to “we are the smartest creatures” as another point that is undergoing a revolution, from calculator and computers, from checkers to chess and go, and whether anything happens with LLMs (whether your bar is Nth percentile human or Best human on AIME etc).

I mention because some people have accepted our intelligence is not privileged (regardless of whether you believe LLMs prove anything), others haven’t internalized it yet, or perhaps haven’t internalized the implications of it yet.

But I think it somewhat feeds into your point about human existence / non-extinction being a thing, whether due to events outside our own control (big meteors or solar death) to those that are (nuclear war, or perhaps an AI at some point).

But nonetheless appreciated your writing about the various revolutions on “we are special”, definitely food for thought!