Are You Suffering from Crisis Fatigue?

Some AI-related news you might have missed, followed by a discussion of what I call "crisis fatigue." (2,300 words)

1. AI Is a Disaster

I mentioned in my last post that Grok, run by Elon Musk’s company xAI, generated sexualized images of underaged girls in response to a user’s inquiry. Now, conservative influencer Ashley St. Clair, an ex-girlfriend of Musk’s who mothered one of his 14 children, is “considering legal action” after Grok undressed her in photos taken of her as a child. WTF.

She writes on X that she also “just saw a photo that Grok produced of a child no older than four years old in which it took off her dress, put her in a bikini + added what is intended to be semen.” Musk, Trump, and the other billionaire fascists — will they ever be held responsible for their criminal, immoral, murderous actions? Why do we have to live in a dystopian hellscape of their creation?

Meanwhile, my social media feeds continue to be saturated with noxious AI-generated slop and deepfakes. In addition to fake videos of Venezuelans celebrating the forced removal of Madura, the video below has 4.4 million views right now and 75,000 likes:

Utter slop — even if the point is to poke fun at Trump (though I’m not sure it is). I can’t watch this and not feel as though I’ve suffered a little brain damage.

Another bullsh*t video that popped up on my feed, also with tons of views, is this:

Not sure if you’ve come across Danny Sapko’s videos — he’s a musician with a good sense of humor who posts quirky takes on the music scene. He’s also been railing against AI recently, as have other influencers like Rick Beato, and just posted this video:

What the f*ck is with that blackface clip? And sure, it’s kinda funny, I guess, to see Baby Vance playing the bass (or “behs”), but is this really what we want the internet to become?

Just two weeks ago, The Guardian reported that “more than 20% of videos shown to new YouTube users are ‘AI slop,’” according to a recent study. That presumably means lots of children are being exposed to this crap. I’m reminded of Sam Altman being asked a few years ago about what keeps him up at night, and he responded something like: “The possibility that we’ve already done something harmful and irreversible.” I can’t find the original quote (send it to me if you can!), but this has been rattling around in my head ever since. Sorry, Sam, but you have:

LLMs (large language models) have had disastrous consequences for society — and the worst is yet to come, as companies continue to pour ungodly amounts of resources into building an “AI God” to fulfill their bizarre TESCREAL fantasies of creating a techno-utopian civilization full of 10^58 posthumans among the stars.

According to one estimate reported by the World Economic Forum, $1.5 trillion has been wasted on the AGI race. Imagine for a moment how much better the world could be if it had been spent on improving social welfare, eliminating poverty, enabling universal health care, mitigating the climate catastrophe, etc. What a monumental loss of resources on these stupid enslopificatory machines now flooding the information superhighway with mind-numbing nonsense.

Gianmarco Soresi, as usual, captures the idea with humor:

Now on to the main topic of this post:

2. The World Is a Mess

The world is a dumpster fire right now, due in large part to the fascist-imperialist regime in charge of the US. We have at least 3 more years of this, and following the brazenly illegal actions taken in Venezuela, it now looks more than likely that Trump will actually attempt to annex Greenland, kidnap the political leaders of Columbia and Mexico, strike Iran, invade Cuba, and/or take actions to make Canada the 51st state.

I don’t make predictions — except when I predict that I won’t make future predictions! :-) — but if I were forced to bet, I’d put money on at least one of the scenarios listed above actually happening this year. The Trump administration appears to be quite serious about their jingoistic agenda of world domination, though Trump is a capricious madman guided by a conspicuous absence of principles, so it’s entirely possible that the US won’t try to expand its territory. Time will tell and, unfortunately for us, there’s a lot of anxiety in waiting to find out.

Meanwhile:

Israel is committing more atrocities in Gaza and the West Bank.

The CDC has reduced the number of recommended vaccines for children from 17 to 11, with those targeting rotavirus, hepatitis A and B, seasonal flu, and meningitis now being “more restricted.” As measles outbreaks spike — 49 in the US during 2025 alone — the new schedule implemented under Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s supervision will kill people. This is malpractice of the highest degree.

And let’s not forget that the environmental crisis continues to worsen by the day. Did you hear, for example, that 2025 was the second warmest year on record, ever — behind 2024? It’s possible you missed this amid the cacophony of people screaming about other crises. There are simply too many tragedies happening right now to keep track of them all. No one can hear the poor climatologists sounding the alarm.

Fortitude Is Finite

This situation brings to mind what I like to call crisis fatigue.1 We’ve all experienced such fatigue — as someone who’s worked on global catastrophic risks since 2009, I most certainly have. Indeed, I can pinpoint the exact moment I first felt overwhelmed by the polycrisis — by the harsh reality that we are “superfucked.” It was the night that Trump was elected for the first time. Suddenly, the abstract risks that I was studying and writing about seemed all-too-real.

Incidentally, the philosopher Emmanuel Levinas once quipped that the phrase “harsh reality” is a pleonasm — and unnecessary repetition of words. I love the dark humor!The fact is that our cognitive-emotional resources for worrying about world affairs — not to mention the various struggles within our own lives — are strictly limited. Fortitude is finite, and so is the mental energy necessary to pay attention to and care about what’s going on in the world. Attending to one crisis often means neglecting another. (Consider Greta Thunberg pivoting away from climate change to focus on the Gaza genocide.) Attending to multiple crises simultaneously risks catapulting us into a state of burnout, depression, and panicked anxiety. The world is a relentlessly awful place, though this becomes more obvious in times like these than in those of relative peace and stability (if only for those of us in the West). Adding insult to injury, the world didn’t need to be this way: the difference between how good the world could be and how bad it actually is, is huge.

The implication of crisis fatigue is that it impedes us from effectively dealing with the multiplicity of threats that constitute the polycrisis. We need to care about all of these threats — we can’t stop caring about climate change because American fascism is extending its imperialist hammer in hopes of smashing other states to pieces. We can’t stop caring about the humanitarian crisis in Gaza because climate change is worsening. We can’t stop caring about the synergistic links between fascism, social media, and AI, which have enabled informational pollution like conspiracy theories and deepfakes to be generated at mass scale.

Yet we can’t care about all of these things. It’s too much. It’s too overwhelming. It’s a recipe for burnout and nervous breakdowns.

The Surprising Explosion of Ignorance

Here I think about another phenomenon similar to that of rational ignorance: since we can’t know everything, we have to (rationally) choose what not to know. As a philosopher and historian with a dilettantish understanding of many other fields, I have consciously decided that, despite my fascination with mathematics, I’m never going to get past calculus (and, sadly, my knowledge of calculus has accumulated a thick layer of mental dust over the years, meaning that I probably wouldn’t pass an AP calculus class at this point).

This brings to mind yet another issue that almost no philosopher has written about, despite it being, in my view, one of the greatest challenges of our time. I call it crisis overload.

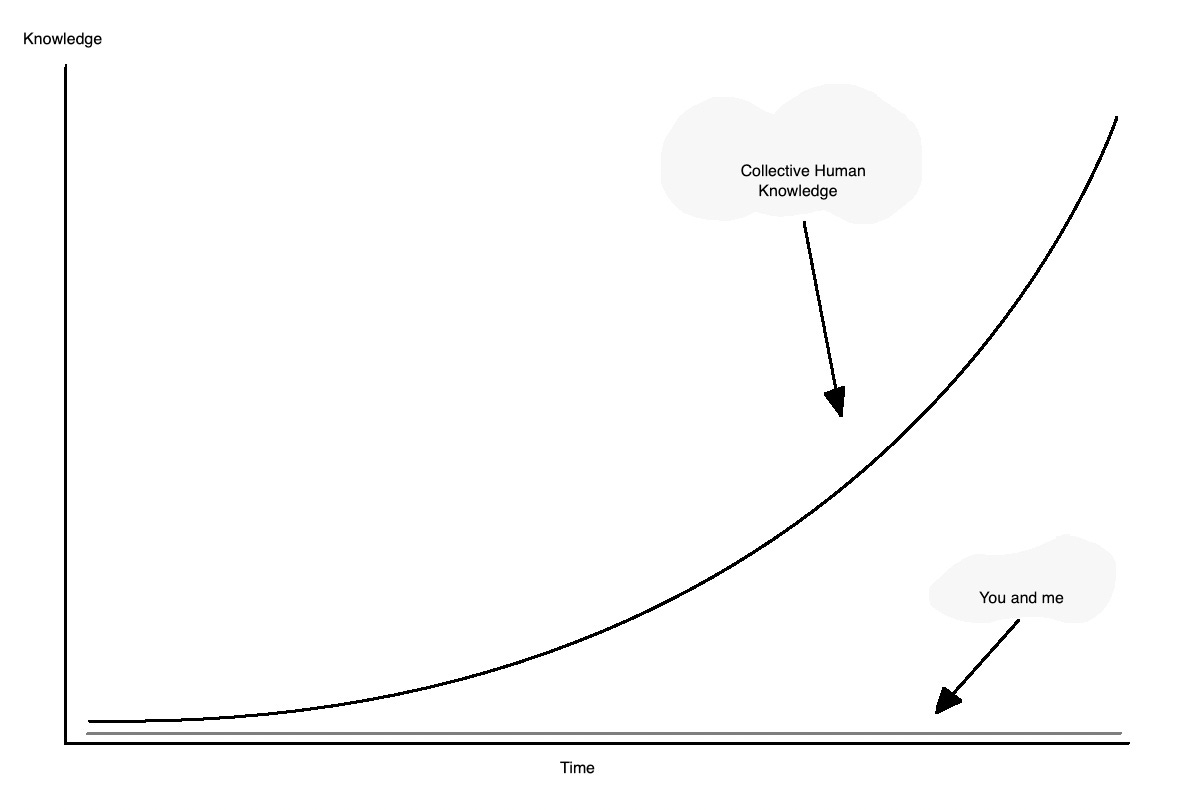

For example, consider that over the past few centuries, collective human knowledge has grown (more or less) exponentially. You can think of such knowledge as everything encoded in the books that fill a university library. This knowledge pertains to our societies and cultures, geopolitics, economics, legal institutions, jurisprudence, religion, science, technology, and so on.

Now, at the same time that collective knowledge has exploded, the capacity for individual humans to know stuff has remained almost entirely fixed. In fact, our bodies and brains have hardly changed since (at least) behaviorally modern humans emerged some 50,000 years ago.

What does this mean? What are the implications of such a divergence? If one defines “ignorance” as the difference between what the collective whole knows and what any single individual can know, then ignorance has grown in proportion to collective knowledge — i.e., exponentially. There is a very real sense in which people today — you and me — have never been so ignorant.

The underlying reason is that time, mental energy, and memory are finite resources. However clever one is, and sedulous one studies, there is simply no way to master more than a tiny fraction of human knowledge. One cannot know more than a minuscule fragment of what is known. Put differently: everyone today knows almost nothing about most things. That is simply our contemporary epistemic predicament.

This is different from crisis fatigue, though still related: both concern the fact that we are now confronted by an unprecedentedly complex world and threat environment. There are just so many major problems in the world — captured by what the Club of Rome called the “world problematique” — that we have neither the emotional nor cognitive resources to effectively tackle them.

That leaves us in a strikingly vulnerable situation: literally billions of people are rowing the boat of civilization, but no one is steering or navigating — because steering and navigating requires a degree of understanding the tangle of messy complexities of our world that no single person, group of people, or institution could ever achieve.

The Breadth-Depth Tradeoff

Another way to put this goes as follows: there is a breadth-depth tradeoff with respect to understanding our world and the myriad dangers we confront. Because of the three limited resources specified above — time, mental energy, and memory — you can’t have both breadth and depth. The deeper your knowledge about a topic, the more difficult it becomes to acquire a big-picture, panoramic view of the entire human predicament. And the higher up you climb toward the mountain’s peak, the more details you’ll miss below. Polymathy is dead: it was once possible for single people to master multiple domains of human knowledge. That is no longer the case — our libraries have grown too large, and the world has become too messy.

I myself made a conscious decision 15 years ago to trade depth for breadth, given a strong penchant for seeing (or trying to see) the big picture. I didn’t want to become a philosopher or neuroscientist consumed by extremely narrow, particular problems — not that there’s anything wrong with that; it just isn’t my cup of tea!

But of course this has come at a cost. I couldn’t, for example, extemporize a commentary on all the canonical philosophical texts the way these two philosophers very admirably do. Instead, I traded knowledge of philosophical history for knowledge of neuroscience, global catastrophic risks, and AI ethics. There is just too much to know, and too little time.

Fortunately, “There Is Infinite Hope” - Kafka

The phenomena described above are one reason I think humanity is superfucked, a term I half-jokingly “coined” years ago when I was an active member of the TESCREAL movement. A rather gloomy prognosis, I know, but here I like to leave folks with an uplifting quote from Franz Kafka, apparently uttered to his biographer and friend Max Brod: “Oh, hope enough, infinite hope”! The joke, of course, is that Kafka then added: “Just not for us.” :-)

The frenetic news cycle right now, driven by the fascist whims of a clearly imperialist Trump administration, is genuinely overwhelming. If you feel that way, you are not alone. Crisis fatigue weighs heavily on me, too, and I worry about the way such fatigue and its twin sibling, crisis overload, are impairing our ability to effectively address the expanding list of existing and emerging threats — the polycrisis. The only answer I have to this plight was outlined in this newsletter article.

But what do you think? Have you also experienced crisis fatigue? How do you manage it? Does anything give you hope — infinite hope(!)? Please leave your thoughts below. Even if I don’t respond to everyone, I do read all comments left.

Next up: an article on the history of the TESCREAL movement, which I hope you’ll enjoy!

Before you go, I’m curious — because I’d like to make this newsletter as good as possible and worthy of your time. Do you think articles like this should be split in two and published separately? The present post is, basically, two articles smashed together — because I worried that a shorter piece with some random (but hopefully interesting!) AI news isn’t substantive enough, and the second half is too philosophical to stand on its own (readers might get bored?). What do you think? Feedback on this would be incredibly useful!

As always:

Thanks for reading and I’ll see you on the other side!

Is there another term for this? If so, I’m not familiar with it.

During the first Trump administration, I tried so hard to keep up with everything that now that we're in his second term, my stamina has greatly diminished to deal with all the crises. But I've been mulling two things in my head recently that feels relevant to crisis fatigue. One was a Bluesky post from Tressie McMillan Cottom where she wrote that Liz Neely shared in her newsletter,

"In 2026 I want all of the decent people to remember one thing.

You aren’t meant to be this disciplined, this self-sacrificing to survive. The environment is supposed to support good living. We can have that. You are not a failure. That is politics.

That is all."

Also been listening to a track titled "Human" on Brandi Carlile's most recent album which has these lyrics:

"Baby, you're only gonna hurt your back

Looking down like that, cut yourself a little more slack

Baby, you're gonna have a heart attack

And they won't thank you, they don't make awards for that"

Feels like this year is hard already, and it's less than a week in. It's kind of hard not to feel hopeless, but I think one of the things that is important to remember that while we must acknowledge these terrible things, it's also important to remember the things that make life worth living like being with people we love, listening to music and art, reading, whatever brings you joy, even if it's small. I've always felt like the cruelest people are just not capable of having fun. And by finding joy in small things can serve both as a kind of resistance but also a way to keep us tethered in the chaos by reminding us of the things we are fighting for. And if we get burnt out with crisis fatigue, we won't have the will or energy to fight back.

Liz Neely's Newsletter: https://buttondown.com/liminalcreations/archive/year-2-week-1/

Cottom's Bluesky Post: https://bsky.app/profile/tressiemcphd.bsky.social/post/3mbfgmtxo5c2l?utm_source=liminalcreations&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=year-2-week-1

Brandi Carlile's Song "Human": https://youtu.be/pmeK6vq0A5s?si=F-p1pEoNWsMqUcyr

I can only say I’m in general agreement. I also traded depth for breadth, and see patterns well. I became collapse aware three years ago, have been studying it since, have written about it on substack, and agree we are superfucked.

And I’m giving myself a break now, because I need it and what’s the point? Any and all efforts to push in the right direction drown in the torrent of crisis, and people are choosing wilful/rational ignorance anyway.