A Philosopher Explains Quantum Computers

Or, at least, tries their best to! (8,700 words)

This article on quantum computing is a little different than most others I’ve published so far. Written last year, I never found a compelling reason to share it with newsletter readers. Now seems to be a good time, given that Demis Hassabis, the CEO of Google DeepMind, recently referenced the idea in an interview that’s been making the rounds on social media (below).1

What follows is quite long! Despite being way more technical than what I usually publish here, this aims to be a comprehensive yet relatively accessible introduction to quantum mechanics, quantum computers, and the potential uses of such computers. You can think of it as a mini-book consisting of three chapters: 1, 2, and 3.

Topics discussed include:

Quantum superposition

Quantum interference

Quantum entanglement

Nonlocality

Qubits

Quantum parallelism

Quantum algorithms

Computability

Computational complexity theory

Quantum error correction

Decoherence

Shoes

Tennis balls

I really hope you find this interesting — I’ll return to my usual kvetching about TESCREALism and the reckless race to build AGI next week, probably with an article titled something like: “Ted Kaczynski and Eliezer Yudkowsky: Two Peas in a Pod,” which will explore the surprising links between Kaczynski’s radical neo-Luddism and contemporary AI doomerism of the sort championed by Yudkowsky. Fun stuff!

Without further delay, here’s this week’s lengthy article!

Chapter 1: Quantum Mechanics: The Basics!

Understanding quantum computing requires some background knowledge of quantum phenomena relating to superposition, interference, entanglement, and measurement. Let’s consider these in turn.

What makes quantum computers (and quantum computation) different from so-called “classical” computers (and “classical” computation) — that is, the sorts of computers and computation that are ubiquitous today — is that quantum computers exploit the perplexing properties of quantum mechanical phenomena. Consider the fact that all matter in the universe exhibits wave-like properties. This includes macroscopic objects like you and I, cars and cats, tennis balls and planets. However, the wavelength associated with an object decreases inversely with that object’s mass. The more massive the object, the smaller its associated wavelength. This is why macroscopic objects like you and I do not exhibit wave-like behavior. We behave, instead, like discrete entities in the world. This is what “classical” physics is very good at describing.

However, when one zooms-into the submicroscopic realm of protons, electrons, and photons — that is, particles of light, which have no mass, unlike protons and electrons — the wave-particle duality of these entities becomes very significant. Quantum computers exploit this fact of nature: very tiny things behave as both particles (discrete entities) and waves. These properties of quantum particles can then be manipulated in various ways to perform useful computations, such as simulating physics and solving certain computationally complex problems (more on this below).

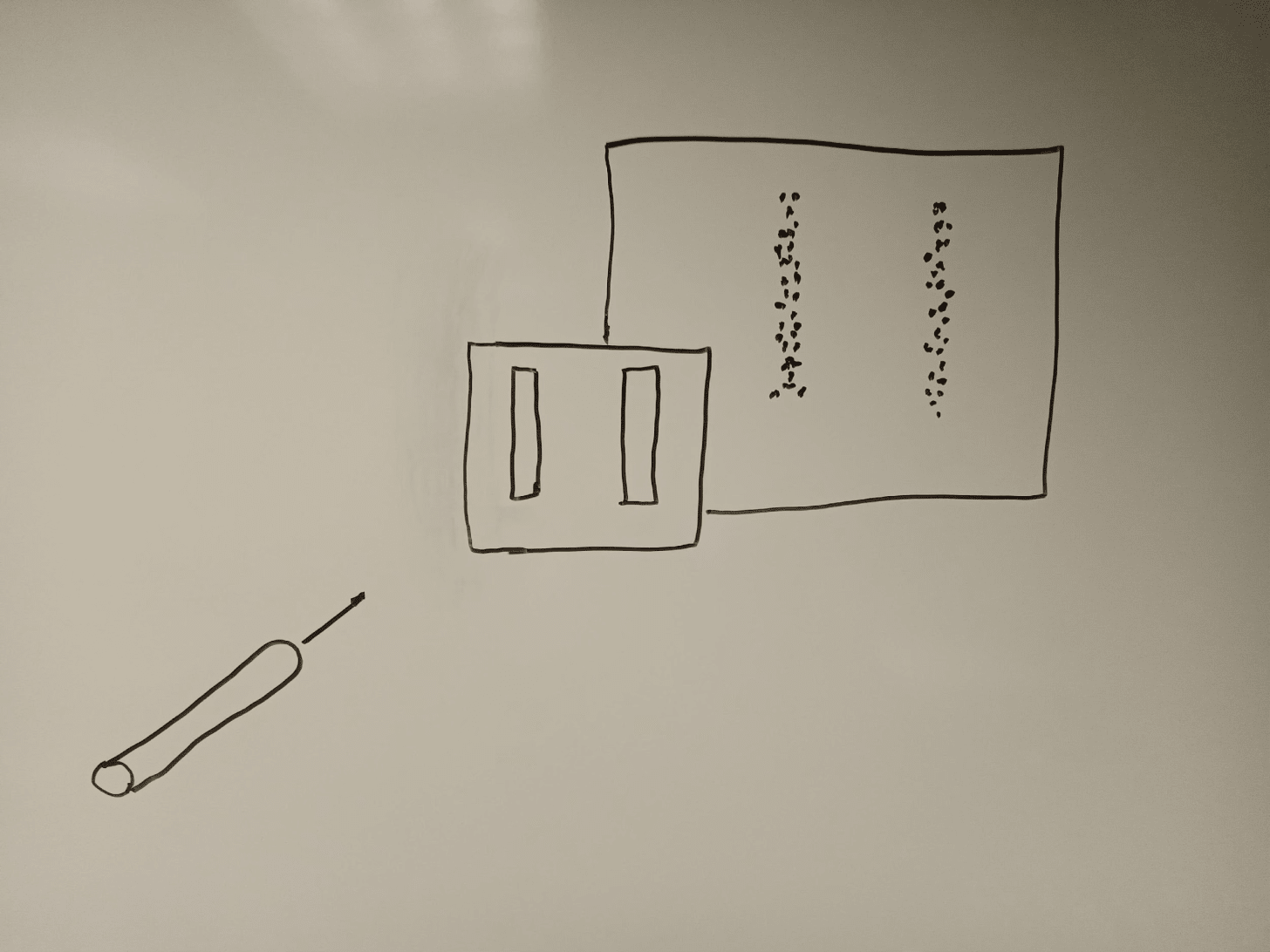

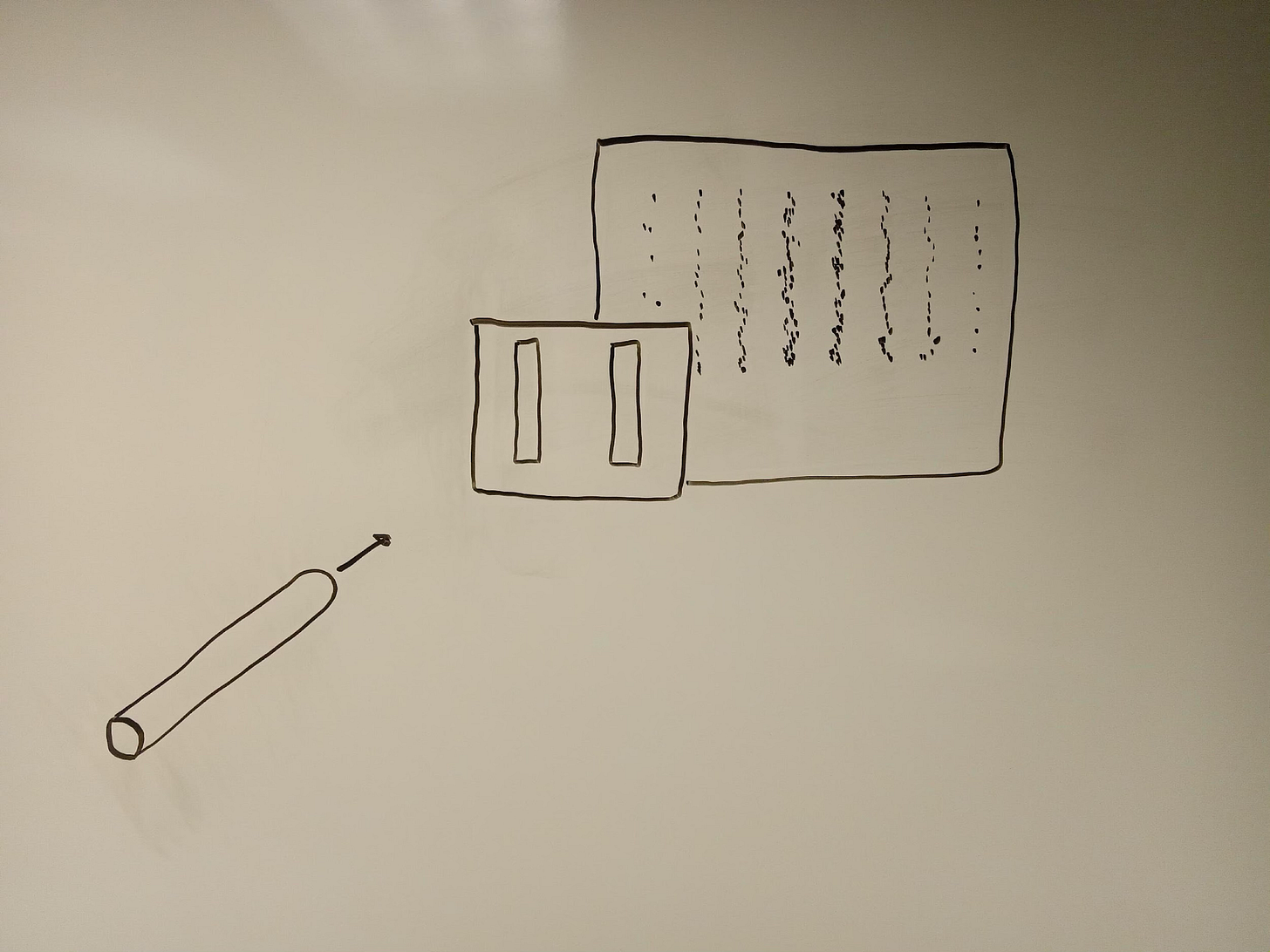

An illustration of the wave-particle duality of quantum particles comes from the famous “double-slit” experiment. Let’s begin by imagining the experimental set-up using macroscopic objects like tennis balls (see figure 1), which we can describe as “classical” particles, since they obey the laws of classical physics—i.e., the physics of objects massive enough for their wavelengths to be irrelevant.

Consider a “gun” that shoots out tennis balls in the general direction of a barrier, which consists of two rectangular slits just wide enough for a tennis ball to pass through them. On the other side of this barrier is a wall covered in velcro, which the tennis balls can thus stick to. The gun that shoots out the tennis balls is not very accurate, so only some of the tennis balls end up passing through one of the two slits in the barrier.

Now, imagine turning on the gun and shooting tennis balls toward the barrier, one at a time, for several hours. What would we expect to see? A whole bunch of tennis balls would hit the barrier and bounce back toward you and the gun, but some of the tennis balls would pass through one of the two slits. You would then see two rectangular areas on the velcro wall covered in tennis balls.

There’s nothing mysterious about this scenario — it’s exactly what you would intuitively expect, because macroscopic objects like tennis balls behave as discrete entities rather than as waves. The ball passes through one or the other slit, and ends up on the velcro wall just behind that slit.

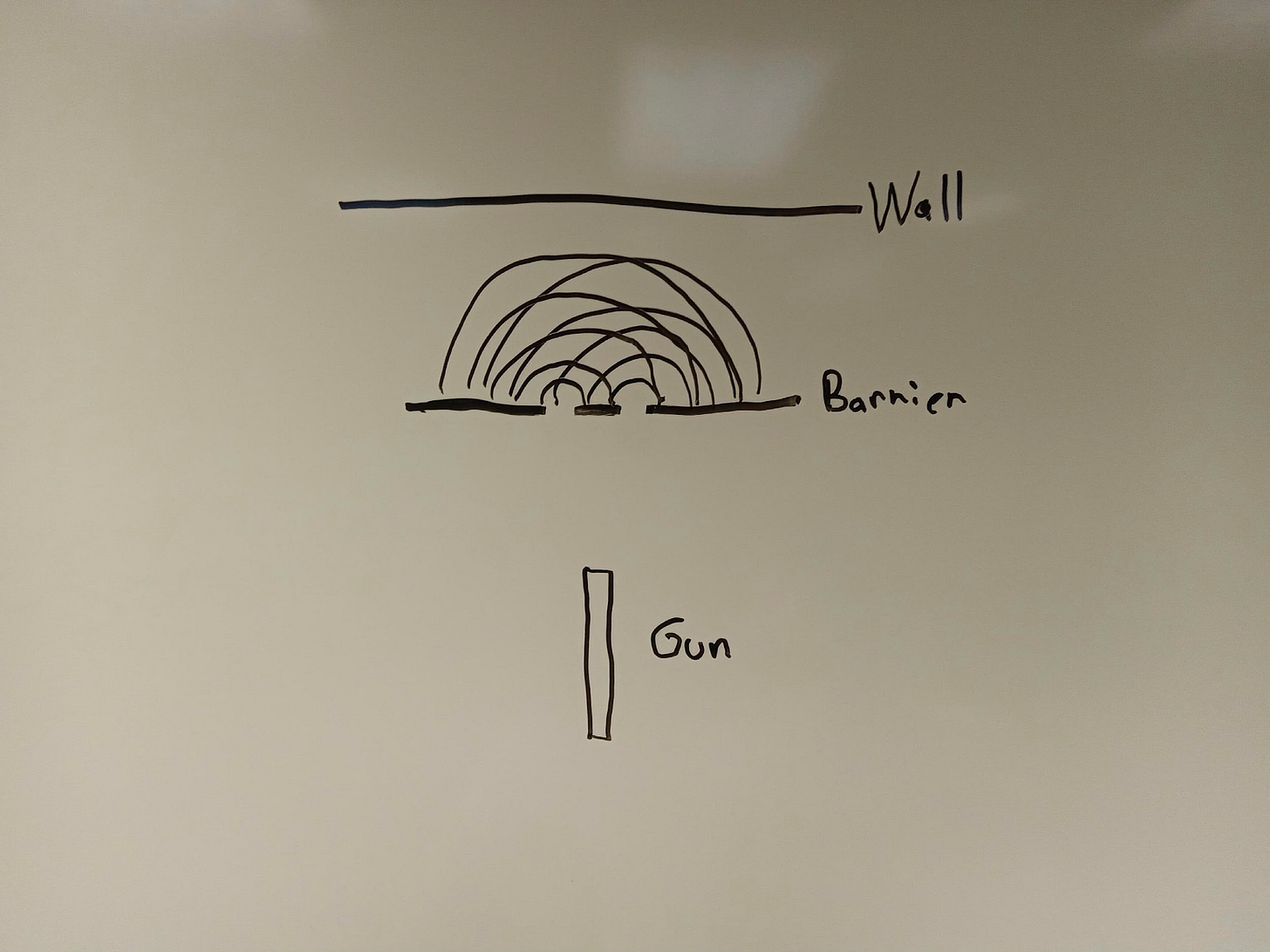

But because very small entities have properties of both particles and waves, this is not what occurs with entities like photons or electrons. If you replace the tennis balls with, say, electrons, and shoot them one at a time (just as you did with the tennis balls), you will find that the electrons cluster together on the wall behind the barrier in multiple locations (see figure 2). Between these locations where the electrons cluster together, there are gaps in which no electrons appear on the wall.

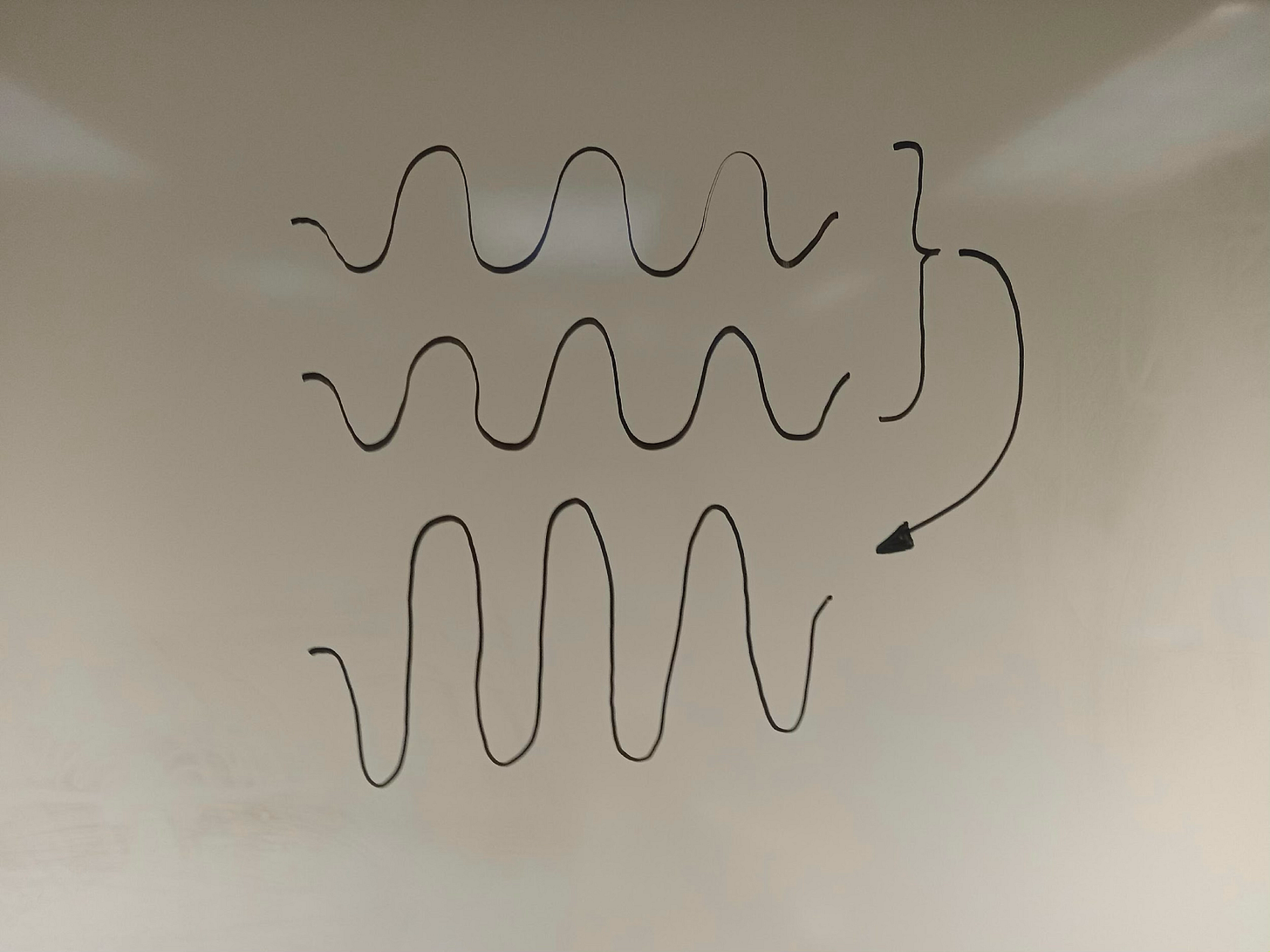

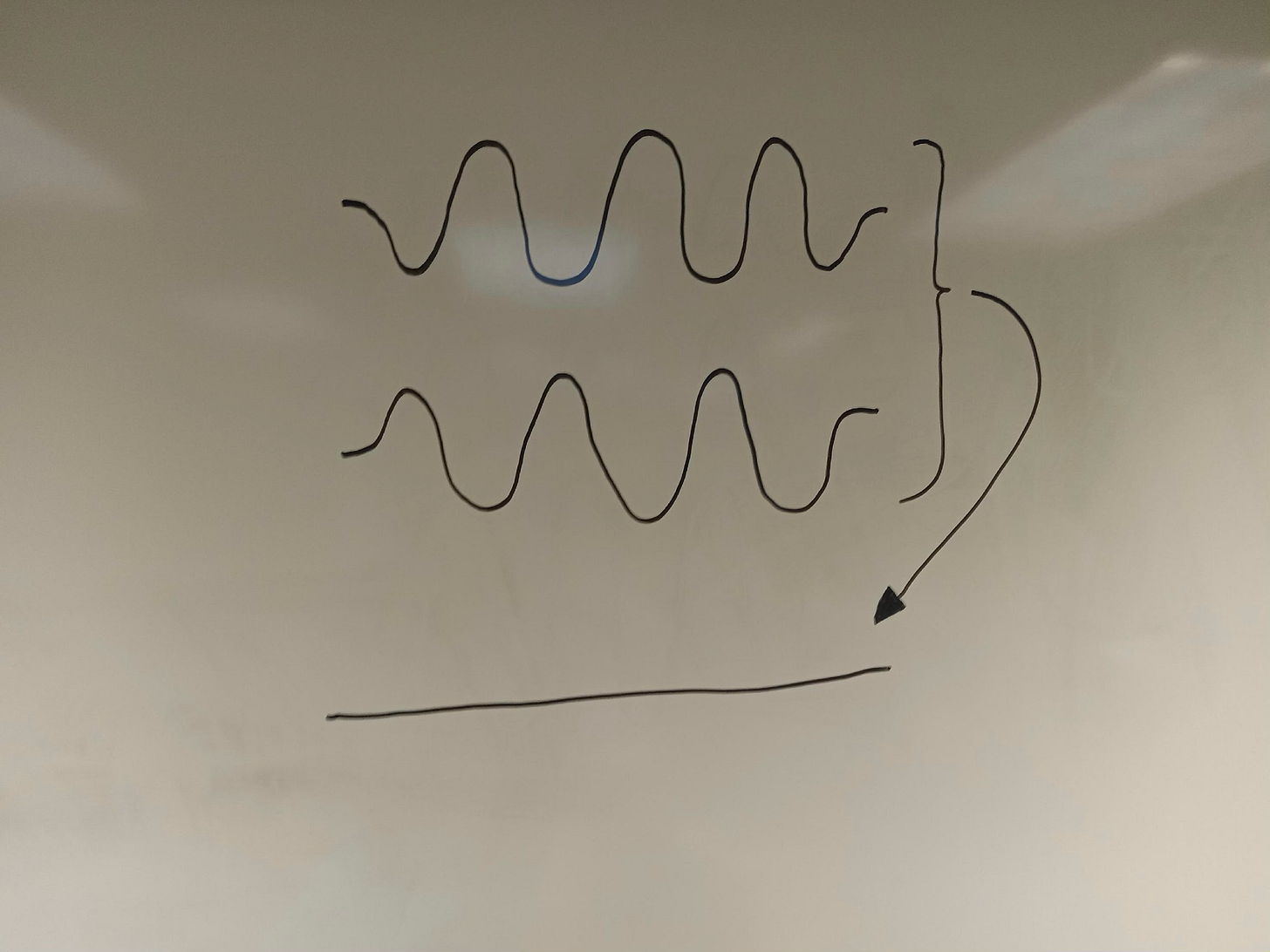

Why does this happen? Because, although the electrons are shot out of the gun one at a time — as “quanta” — they pass through the slits as waves. And when waves pass through two slits, they diffract around each slit. The diffracted waves that emerge on the other side of the barrier move away from the slits in a circular manner (see figure 3), which enables these waves to interfere with each other: in some cases, the peak of one wave, from one of the two slits, coincides with the peak of the wave from the other slit; in other cases, the peak of one wave, from one of the slits, coincides with the trough (or low-point) of the wave from the other slit. When the wave then hits the wall behind the barrier, it manifests itself as a single, discrete particle in a specific place on the wall.

Interference, Superposition, and Measurement

There are four important points to make about this.

First, when the peak of a wave coincides with the peak of another wave, the amplitude (or size) of the two waves is added together. Consequently, the amplitude of the resulting wave — i.e., the combination of these two waves added together — is twice as large. This is called “constructive interference.”

In contrast, when the peak of a wave coincides with the trough of another wave, the amplitudes of the two waves (assuming these amplitudes are equal, for the sake of simplicity) cancels out. Consequently, the amplitude of the resulting wave becomes zero, due to “destructive interference.” (See figures 4 and 5.) This is the way that all waves behave — e.g., if you were to perform the double slit experiment half-submerged in water, you would find the waves interfering on the other side of the barrier in exactly the same way.

Second, when the wave of an electron reaches the wall behind the barrier, it is, so to speak, “forced” to choose a specific location. At this point, it manifests as a particle. But before it manifests as a particle, it behaves like a wave, essentially passing through both slits simultaneously. Indeed, if it didn’t pass through both slits simultaneously in a wave-like manner, then there wouldn’t be the “interference” pattern on the wall behind the barrier, which can only result from something behaving like a wave. (If it only passed through one of the two slits, instead of both, then you’d see the exact same pattern as the tennis balls on the velcro wall.)

Physicists refer to this strange phenomenon as superposition: the electron, in a sense, is in two states at the same time — one state corresponding to “passing through the first slit,” and the other corresponding to “passing through the second slit.” Superposition is one reason that quantum computers could solve some problems exponentially faster than classical computers, as we’ll discuss more in chapter 2.

Third, although the electron, in a very perplexing way, passes through both slits simultaneously, it manifests as a single particle in a specific place on the wall behind the barrier. The reason is that the wall acts as a kind of measurement, and whenever quantum systems in superposition are measured, they always “collapse” into some particular state.

This is very different from our own experiences on the macroscopic level, where the wave-like behavior of macroscopic objects is negligible. To paraphrase one quantum computing expert, Scott Aaronson (see below), superposition is only something that quantum particles like to do in private. As soon as one looks to see where exactly the particle is, the wave-like behavior disappears and suddenly the particle manifests in some particular place. But where exactly does it appear?

This leads us to the last important point. The probability of finding a particle, such as the electron in our double-slit experiment, at a specific location is a function of the amplitudes of its wave-like behaviors. When the two waves that emerge from the double slits interfere constructively, the probability of finding an electron — if one were to measure it — is very high. When the two waves interfere destructively, the probability is very low (or quite literally zero).

Hence, the interference pattern of discrete electron-particles on the wall corresponds to the constructive and destructive interference of its waves. That is to say, the electrons appear mostly where the peaks of its two waves coincide, and they don’t appear where the peaks and troughs of its waves coincide. In other words, combine the amplitudes of the two waves and you get the probability of the electron actually appearing there if a measurement of the system is taken.

Unsolved Puzzles

The quantum phenomena of superposition and interference are crucial for understanding why and how quantum computers could be far superior to classical computers in certain respects. As the renowned physicist Richard Feynman once quipped, “the double-slit experiment has in it the heart of quantum mechanics,” to which he added, “in reality, it contains the only mystery.”

The mystery here is what exactly is going on at the quantum level: we know what happens — as described above — but we don’t really understand why. For example, consider that there are multiple locations on the wall, behind the barrier, where the waves from the single electron interfere constructively. The probability is thus high that the electron will appear in one of these locations. But why one location rather than another? Why in this place where the waves interfere constructively rather than that other place where they also interfere constructively? No one knows.

Another puzzle concerns the measurement of some system: why do particles such as the electron only want to be in a state of superposition in “private,” to borrow Aaronson’s wording from above? Why is it that measuring, or observing, a quantum system “forces” it to fall into some definite state? Again, we don’t have an answer, and there are many interpretations of what is happening when quantum systems fall into definite states (e.g., perhaps the universe splits into two timelines, a bizarre possibility called the “many-worlds interpretation” of quantum physics).

But scientists don’t need to have an answer to such questions to exploit such phenomena for the purposes of quantum computation. Understanding the way quantum systems behave, even if we don’t know why, is enough for quantum computing technology to work.

Quantum Entanglement

Yet another mysterious phenomenon relevant to quantum computers is called “entanglement.” Whereas the double-slit experiment involves only single particles (being shot out of the gun one at a time, where the particle’s own waves interfere with themselves as they pass through both slits simultaneously), entanglement involves two or more particles.

Two particles can become “entangled” in numerous ways — for example, by interacting with each other. Once entangled, the state of one particle cannot be described independently of the state of the other particle. Consider an example often used by physicists: imagine that I have a pair of shoes and two boxes. I put the left shoe in one box and send it to my friend Sarah, and I put the right shoe in the other box and send it to my friend Dan. I then tell Sarah and Dan exactly what I have done, but don’t reveal to them whether they will be receiving the left or right shoe.

If Sarah receives and opens her box first, she will immediately know that Dan received the box with a shoe for the right foot. That is to say, looking and seeing which shoe she received provides information not just about the shoe I sent her, but about the shoe that I sent Dan. In this way, you could say that the shoes are “entangled,” as the “state” of one box is not independent of the other. If there’s a left shoe in one box, then there must be a right shoe in the other box. There is nothing mysterious about this situation.

But there is something mysterious about the quantum analog of this example. Consider that particles like electrons have a property that physicists call “spin.” An electron could be “spinning” either “up” or “down.” Those are the two options, just as left and right are the two options for the aforementioned shoes. Now, if two electrons become entangled, they will always have opposite spins: if the first electron has an “up” spin, then the second electron will always have a “down” spin — and vice versa.

Now imagine that I take two entangled electrons and send one to Sarah and the other to Dan. If Sarah receives and examines — that is, measures — the spin of her electron to be “up,” she will immediately know that the spin of Dan’s electron is “down.” However, because of superposition, the electron that Sarah (and Dan!) received is neither up nor down until she examines — that is, measures — it. In other words, both electrons are in a superposition of “up” and “down,” and it is only when Sarah measures her electron that it is “forced” to choose between a definite “up” or “down” orientation. (Yes, this is really, really weird stuff!) Sarah could have thus found her electron with a “down” spin, in which case she would immediately know that Dan’s electron has an “up” spin.

This clearly contrasts with the shoe example, in which the shoe in Sarah’s box is already in a definite state: it is the left-foot shoe. Sarah simply doesn’t know this. If the shoe were in a quantum state of superposition, it would be neither left nor right until Sarah opens the box, thereby making a “measurement” of which foot (left or right) the shoe that she received is.

Non-Locality

This is extremely counterintuitive, once again. It is not how things work in our macroscopic world, and so we lack the intuitions necessary to fully comprehend what the mathematics, backed by empirical observations, unambiguously imply.

Even more mysterious is how the spins of the electrons are correlated: by “forcing” one of the electrons into an “up” or “down” state, the other electron is instantaneously “forced” into the opposite state. It is almost as if the first electron measured sends a signal — faster than the speed of light, because this occurs instantaneously — to the second electron saying: “Hey! I now have a definite ‘up’ orientation, so you should have a definite ‘down’ orientation.” These electrons could be literally billions of miles away from each other: as soon as one electron is measured, or observed, the other electron assumes a definite state that is opposite of the first.

This leads some to speculate that information could be sent over vast distances faster than the speed of light, via entanglement. However, transferring information via quantum entanglement faster than the speed of light is not possible, and indeed there is no information exchanged from the first electron measured to the second. That is to say, the first electron does not “communicate” its spin to the second electron.

Rather, what happens is that when two particles are entangled, they become part of the same “wavefunction.” A wavefunction describes how an isolated quantum system changes or evolves over time. With respect to the double-slit experiment, the wavefunction associated with each electron shot out of the gun toward the barrier and wall behind it, describes how the electron, behaving as a wave, passes through both slits, interferes with itself on the other side, and creates the interference pattern on the wall (corresponding to the probability of the electron appearing at any given location). That’s what the wavefunction does!

Hence, if two electrons become entangled such that they share the same wavefunction — where this wavefunction isn’t the two electron’s wavefunctions combined, but a distinct new wavefunction that describes the entire system consisting of these two electrons — then any measurement (or observation) made of one electron in the system will “force” the other electron in the same system into some definite state. And since the spin orientation of the second electron must be the opposite of the spin orientation of the first, measuring the first electron as having an “up” spin instantaneously causes the second electron to have a “down” spin—because, once again, they are part of the very same quantum system that one “forces” into a definite state by measuring or observing any part of that system.

This phenomenon is call “nonlocality,” whereby quantum systems that might not be localized in space (again: entangled particles could be separated from each other by literally billions of miles and still exhibit this property) are nonetheless instantaneously correlated. “Classical” physics cannot explain this, nor is there any analog in our own experiences of the macroscopic world, which is governed by “classical” physics.2

Conclusion

That does it for chapter 1. Congratulations on making it to the end of this short intro on quantum mechanics! We now turn to the ways that quantum computers exploit the phenomena of superposition, interference, entanglement, and measurement.

Chapter 2: The Potential Power and Limitations of Quantum Computers

In chapter 1, we discussed three important properties of quantum systems: superposition, interference, and entanglement, along with the phenomenon of measurement. These are foundational to quantum computing. They are the reason that quantum computers could be exponentially faster and more efficient than classical computers with respect to certain kinds of problems.

What the Heck Are Qubits?

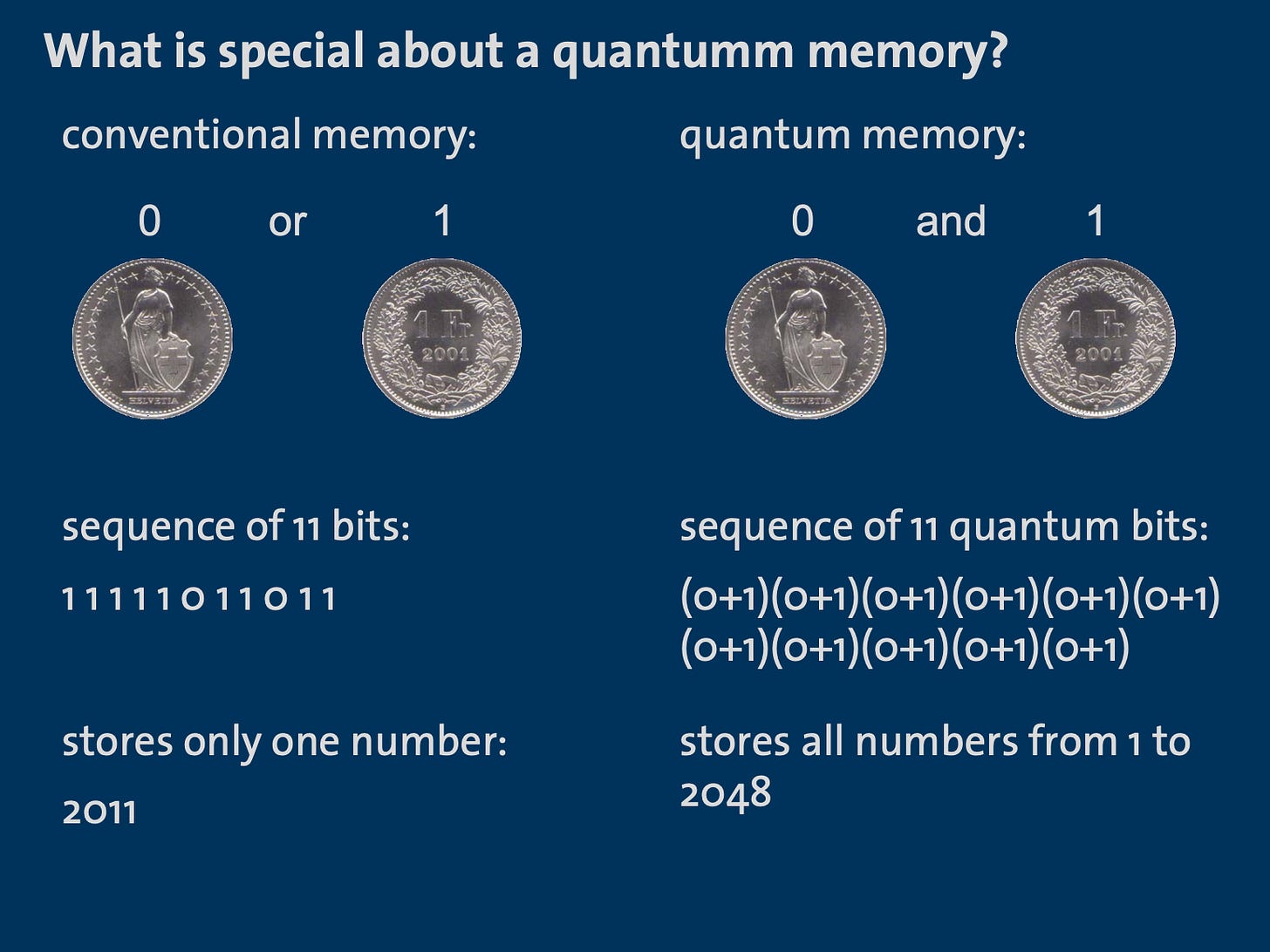

Consider that classical computers encode information as bits, which take the form of either a 1 or 0. In contrast, quantum computers encode information as qubits, short for “quantum bit.” Unlike classical bits, qubits are measured as either 1s or 0s, but prior to being measured they exist in a superposition of both 1 and 0. This means that qubits can store far more information than bits.

For example, take the following sequence of eleven classical bits: 11111011011. How much information do these bits together store? The answer is only a single number. When translated from binary code, this sequence gives the number 2011. Compare this to a sequence of eleven qubits. Because of superposition, these qubits are neither 1s nor 0s, but exist in a superpositional state of (0+1) prior to being measured. Hence, listing (0+1) eleven times yields: (0+1)(0+1)(0+1)(0+1)(0+1)(0+1)(0+1)(0+1)(0+1)(0+1)(0+1). How much information can these qubits store? The answer is every single number from 1 to 2,048.

To underline this point, eleven classical bits stores just one number. Eleven qubits stores 1, 2, 3, 4, … all the way up to 2,048. That’s a huge difference! (See slide 5 of this presentation for citation.)

More generally, simulating some number n of qubits on a classical computer would require approximately 2^n computational steps, because n qubits can be in a superposition of 2^n states. Hence, as the number of qubits increases, the number of steps needed to match the computational power of quantum computers grows exponentially.

It would thus require 8 classical steps to simulate 3 qubits (2^3), and 16 classical steps to simulate 4 qubits (2^4). Now consider a quantum computer that contains 300 qubits. Simulating these qubits on a classical computer would require roughly 10^90 steps — since 2^300 roughly equals 10^90 — which is larger than the total number of atoms in the universe (estimated to be approximately 10^80). That is the extraordinary power of superposition.

Entanglement, then, is what enables quantum computers to perform many computations at once. This is to say, in a single operation, quantum computers can manipulate multiple values of the qubits at the same time, whereas classical computers must manipulate each value of the bits individually, one at a time.

For example, if two qubits are entangled — meaning that they are part of the same quantum system, described by a single wavefunction — and one is measured to have a value of 1, then the other qubit will immediately take the value of 0. In classical computing, it is not possible to create an algorithm where two bits have no value, but nonetheless have opposite values, though it is possible in quantum computing.

This enables a phenomenon called quantum parallelism, which contrasts with the way that computation happens in a classical microchip: serially rather than in parallel. Quantum parallelism is why quantum computers can perform calculations much faster than classical computers, including the most powerful classical computers: supercomputers.

Finally, interference is used in quantum computers to determine the correct solution(s) to a problem. When quantum particles are in superposition, the superimposed states of these particles produce wave-like phenomena that can interfere with itself, just as the waves of the electron in the double-slit experiment interfere with themselves to produce the interference pattern seen on the wall. One can thus design quantum algorithms (discussed in a bit) that manipulate the waves associated with particles in the hardware of quantum computers so that the positive interference of these waves corresponds to a correct answer, while negative interference corresponds to an incorrect answer.

For these reasons, quantum computers are not just “better” versions of classical computers. They are fundamentally different, in perhaps the same way that an incandescent light bulb isn’t just a better “version” of a candle — to borrow an analogy that others have previously made.

The Limitations of Quantum Computers

Quantum computers could revolutionize several billion-dollar industries and enable exciting new scientific discoveries. There is, however, a widespread belief that they will be superior to classical computers in nearly every way. This is not true: quantum computers will provide modest speed-ups with respect to certain problems, exponential speed-ups with respect to a few others, and no advantage in certain other cases.

In other words, classical computers will still out-perform quantum computers on particular tasks, as discussed more below. There is no fundamental difference in computability between classical and quantum computers — that is, quantum computers are not able to solve problems that classical computers cannot solve in principle.

The sole advantage of quantum over classical computers is their speed and efficiency at solving problems, including some that would take classical computers centuries, millennia, or longer to solve. That is to say, the exceptional speed and efficiency of quantum computers means that there may be some problems that they can efficiently solve that classical computers cannot, simply because classical computers require impractical quantities of resources to find a solution.

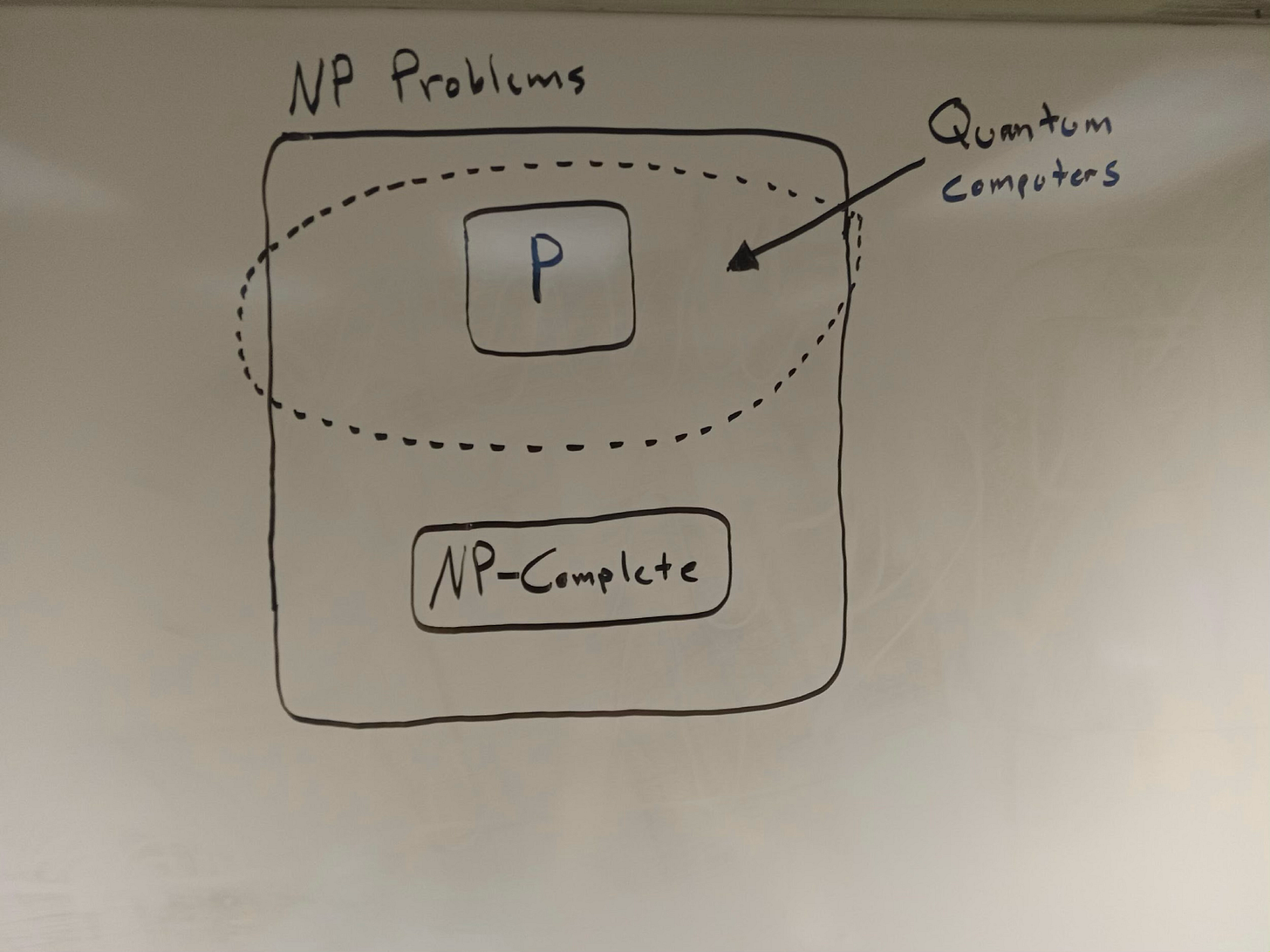

Computational Complexity Theory

To get a sense of the limitations and promise of quantum computers, consider figure 6. This shows three important classes of problems, each defined by their computational complexity, where “computational complexity” concerns the amount of resources an algorithm would need to solve the problems. The greater the computational complexity, the more resources are required — and vice versa.

Decision problems in the class of P are those that can be efficiently solved by a “deterministic Turing machine,” such as the classical computers that we use today.

By “decision problems,” we simply mean those problems that, given some input, have a definite “yes” or “no” answer. Examples include: “Is Paris in Spain?” (no!!) and “Does 4 plus 4 equal 8?” (yes!!).

By “efficiently,” we mean that the problem can be solved in polynomial time, where “polynomial time” refers to an amount of time that increases polynomially with the size of the input. The larger the input, the greater the amount of time needed to solve the corresponding problem, where the input and the time needed are related by a polynomial (a mathematical expression consisting of variables and coefficients).

All P problems are also NP problems, but not all NP problems are — it seems — P problems. In other words, P appears to be a subset of NP. The difference is that NP denotes the much larger class of problems that can be efficiently verified (or checked) in polynomial time. If a program can efficiently solve a decision problem, then it can also efficiently verify that problem, too. Why? Because verifying a solution will always be easier than solving the problem itself. Hence, there are some problems that can, it seems, be efficiently verified but not efficiently solved: these are the NP problems, whereas P problems are those that can be efficiently solved and verified by a deterministic Turing machine.

P = "Yes or no" problems that are efficiently solvable and efficiently verifiable by a deterministic Turing machine, like the computers we currently have.

NP = "Yes or no" problems that are efficiently verifiable but not efficiently solvable by a deterministic Turing machine.The most notorious unsolved puzzle within the field of computational complexity is whether the class of P and NP problems is, in fact, coextensive: does P equal NP, or not? This is to say, are all the problems that are verifiable in polynomial time also solvable in polynomial time? Again, it seems like the answer is “no”: some problems can be efficiently verified but not solved. But we do not know this for sure, and there is a $1 million dollar prize awaiting anyone who can mathematically prove that P equals NP, or demonstrate the opposite.

The final class of computational complexity that’s worth mentioning goes by the name “NP-complete” — the most infamous of the NP problems. It includes any problem that, if efficiently solved by an algorithm, would enable one to solve all the problems in NP. This is a rather esoteric notion, but for our purposes the key point is that, as the philosophers Michael Cuffaro and Amit Hagar explain, “since the best known algorithm for any of these [NP-complete] problems is exponential, the widely believed conjecture is that there is no polynomial algorithm that can solve them” (italics added).

In other words, NP-complete problems appear to require superpolynomial, if not exponential time, to solve, meaning that as the size of the input increases, the amount of time required to solve an NP-complete problem grows at a superpolynomial or exponential rate. Hence, there are ostensibly no algorithms that could solve such problems efficiently.

An example of an NP-complete problem is the jigsaw puzzle: there is no algorithm that can efficiently solve the problem of fitting all the pieces together for any arbitrarily large puzzle because of the combinatorial explosion of different ways the puzzle’s pieces could fit together. (It may help to imagine here a jigsaw puzzle that has no picture on the front; all the pieces are blank.)

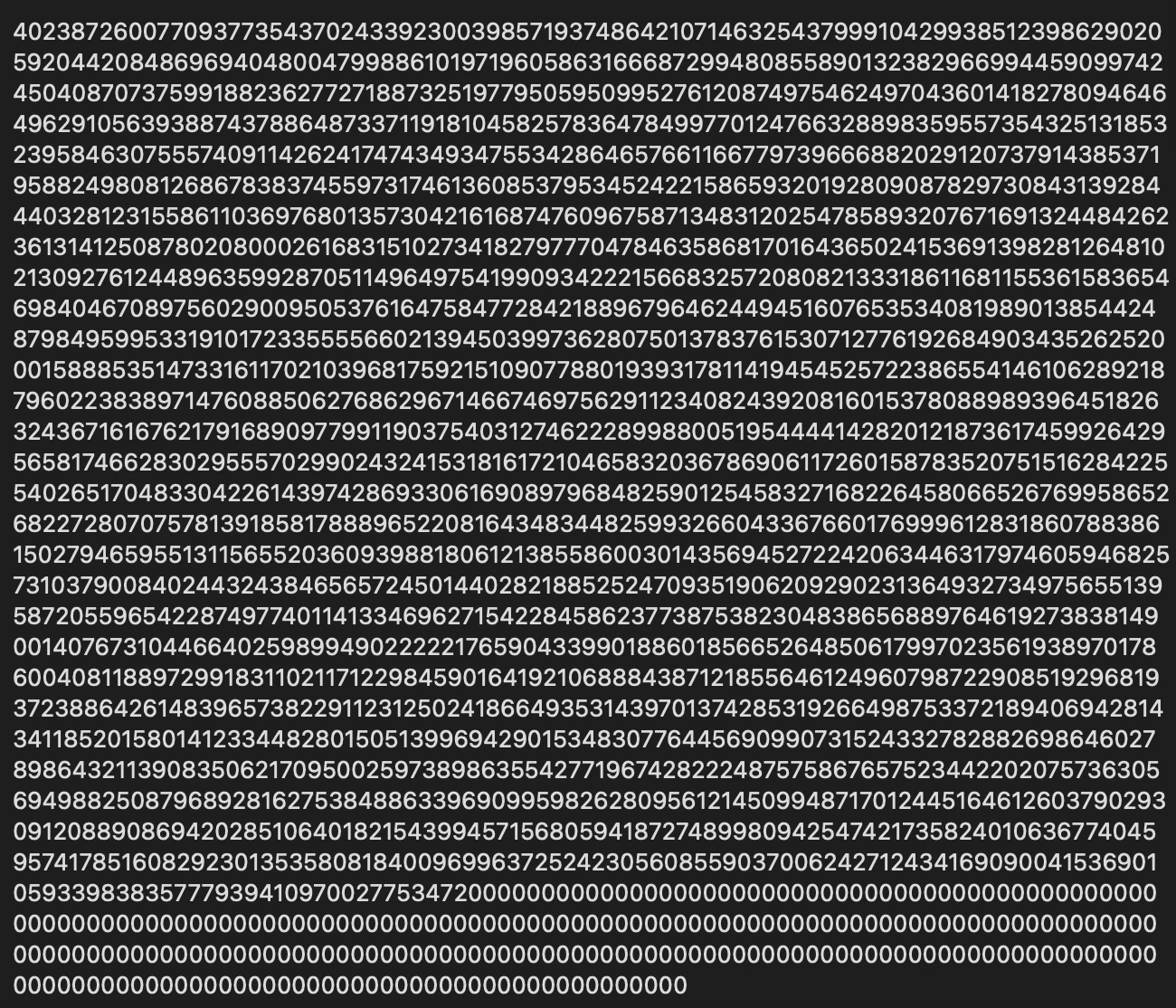

As the number of pieces in the puzzle increases, the problem of finding the correct solution thus becomes computationally intractable — due to this combinatorial explosion. Consider that a jigsaw puzzle with 1,000 pieces yields a number of possible combinations that is 2,568 digits long (whereas the number 2,568 is only four digits long).

To underline the immensity of this number, I have included it below. The factorial of these 1,000 pieces (written as “1000!”) is this:

To find the correct solution to a 1,000-piece jigsaw, the algorithm would thus need to go through each of these possibilities. However, checking to see whether some proposed solution to the puzzle is correct turns out to be quite simple: all an algorithm needs to do is verify that, say, there are no gaps between any of the pieces arranged in some particular way. Using an algorithm to figure out how the jigsaw pieces fit together is, therefore, computationally infeasible, but determining whether the puzzle has been solved can be done in polynomial time (that is, quickly).

Can Quantum Computers Solve NP-Complete Problems?

Okay, so, this brings us back to quantum computers. Computer scientists do not expect quantum computers to be able to efficiently solve NP-complete problems. They will be able to efficiently solve all P problems, which classical computers can efficiently solve. The important difference is that quantum computers may be able to solve some NP problems that are not P problems — that is to say, certain problems that can be efficiently verified but not solved by classical computers.

An example of an NP problem that is (probably) not a P problem is the so-called “factoring problem.” This refers to the task of breaking down large numbers into their prime factors. As we will see in a later section, the most widely used form of encryption used today is called the RSA cryptosystem, where “RSA” stands for the last names of three individuals who first introduced the algorithm in the late 1970s: Ron Rivest, Adi Shamir, and Leonard Adleman.

The RSA cryptosystem is based on the fact that factoring large numbers into prime numbers is enormously hard. As the number that must be factored increases in size, the difficulty of figuring out what its prime factors — the two prime numbers that, when multiplied together, give the number in question — are also grows exponentially.

Classical computers can efficiently verify whether two prime numbers yield another number when multiplied together — you could easily do this on a calculator, if you have all the relevant numbers. But they cannot efficiently solve the problem if given a very large number that is the product of those two primes.

In contrast, quantum computers could leverage their immense computational power to solve the factoring problem: given some large number, they could find the number’s prime factors in polynomial time using a quantum algorithm specifically designed for this purpose. This quantum algorithm, created in 1994 by Peter Shor, is called Shor’s algorithm. Since it is a quantum algorithm, only quantum computers can run it. Classical computers cannot.

Quantum computers are thus limited in the number and type of problems that they can solve. There is no reason to expect them to crack NP-complete problems. But there are some NP problems that fall outside the class of P problems that quantum computers could efficiently solve, such as the factoring problem. This could have profound implications for privacy and security on the Internet once practically useful quantum computers are developed, as discussed later on.

The Fragility of Quantum Computers

Another limitation of quantum computing arises from the fact that quantum systems are extremely fragile. They can be easily disturbed by environmental perturbations. This presents a significant problem because: (a) they need to be isolated from the environment to prevent these perturbations from affecting them, but (b) they must interact with their environment, because this is necessary for us to extract information from them by measuring the states of qubits.

The reason that quantum computers must be isolated from the environment is due to a phenomenon called decoherence. This occurs when environmental perturbations cause quantum computing systems to lose their ability to interfere with themselves — for example, because particles in the computer become entangled with the environment, rather than other particles in the computer.

In the double-slit experiment, decoherence can occur if a measurement (or observation) of the electron shot toward the barrier occurs before it reaches the barrier — rather than this measurement occurring when the electron strikes the wall behind the barrier. Since measurement causes the electron to manifest as a discrete particle with a particular location, observing these electrons before they reach the barrier causes the interference pattern on the wall behind the barrier to disappear. In other words, decoherence causes the electron to pass through only one of the two slits in the barrier in accordance with the laws of classical rather than quantum physics. Hence, if the particles or qubits in a quantum computer undergo decoherence, they also lose important quantum properties necessary for the quantum computer to function properly.

To counteract perturbations that could screw with the functionality of quantum computers, scientists have developed what is called quantum error correction, or QEC. (This is what Hassabis references in the video included in Part I.) In classical computers, errors — which happen very infrequently — can be corrected by simply copying some sequence of 1s and 0s, and then checking whether the two sequences — the original and the copied sequence — match. If a copy is made, and then some errors are introduced to the original, a classical algorithm can correct those errors in the original by ensuring that the information matches the copy.

However, this is not possible with quantum computers, because of the so-called no-cloning theorem. This states that it is fundamentally impossible to clone, by which theorists mean “to create an exact copy,” of any quantum state that is unknown (e.g., because it is in a state of superposition). The underlying reason concerns the probabilistic nature of measurement, given superposition.

Recall the double-slit experiment, once again. Wherever the electron’s waves interfere positively at the wall, the probability is high that the electron will appear; where the waves interfere negatively, the probability is low that the electron will end up there. Similarly, each time a qubit or group of qubits is measured, it may have some probability of manifesting in a particular state, just as the electron in the double-slit experiment has differing probabilities of appearing at different locations on the wall. But one cannot know which state a quantum system is in for sure — that is, with 100% certainty — prior to measuring it.

Thus, it will always be possible for a “cloned” system to manifest in some other state: there is no way to guarantee that the “cloned” system will assume the exact same state as the original system, from which the clone was copied, once it is measured. If a “cloned” system could assume a different state than the original, then it is not actually a clone! This is not a scientific, technological, or engineering problem that we can overcome. It is an insuperable problem arising from the fundamental nature of quantum phenomena.

The goal of QEC (quantum error correction) is thus an alternative approach to correcting errors that appear in quantum computers. These errors happen at a rate of 0.1% to 1%, which is far more common than the rate of errors in classical computers. Scientists have proposed several quantum error correction codes, and this remains a very active field of research. As the number of qubits in, and operations performed by, a quantum computer increases, so does the possibility of errors, resulting in quantum algorithms that produce inaccurate results.

Central to QEC codes is a distinction between physical and logical qubits. The former are the actual qubits in the hardware of a quantum computer, whereas the latter are the qubits utilized by quantum algorithms to process information. Logical qubits can be realized by multiple physical qubits, as in a QEC approach called the Shor code (also named after Peter Shor), which encodes a single logical qubit in nine physical qubits. Encoding logical qubits in more than one physical qubit thus “enhances protection against physical errors” that may arise from the fragility of quantum phenomena in the hardware of such computers (GQAI 2023). Advancements in the field of QEC will be crucial for building scalable quantum computers with practical applications — the topic of our next chapter.

Chapter 3: What Could Quantum Computers Actually Do?

Hype and Hyperbole?

There is a tremendous amount of hype surrounding quantum computing, which bubbles up into the popular media with regular frequency. We’ll likely see examples in 2026. Time magazine, for instance, declared three years ago that:

Complex problems that currently take the most powerful supercomputer several years could potentially be solved in seconds. Future quantum computers could open hitherto unfathomable frontiers in mathematics and science, helping to solve existential challenges like climate change and food security. A flurry of recent breakthroughs and government investment means we now sit on the cusp of a quantum revolution.

At least some of this hype, though, is hyperbolic. As an article in IEEE Spectrum, published the same year, notes: “The quantum computer revolution may be further off and more limited than many have been led to believe.” The article further observes that, with respect to certain problems, the gains provided by a quantum computer are merely quadratic (rather than exponential), which means that the amount of time required to solve a problem with a quantum algorithm is the square root of the time required by a classical algorithm. In other words, if a classical computer requires 100 hours to solve a problem, a quantum computer would require 10 hours (as 10 is the square root of 100).

Yet the gains provided by quantum computers “can quickly be wiped out by the massive computational overhead incurred,” and hence “for smaller problems, a classical computer will always be faster, and the point at which the quantum computer gains a lead depends on how quickly the complexity of the classical algorithm scales.” The only problems that quantum computers will provide exponential speed-ups on are “small-data problems,” to quote Matthias Troyer, the Corporate Vice President of Quantum at Microsoft.

For quantum computers to become practically useful, scientists will need to develop effective QEC (quantum error correction) codes that enable quantum algorithms to process information without crashing — a “blue screen of death” scenario, so to speak. Yet, according to the aforementioned IEEE article, the “leading proposal” right now is that building robust logical qubits to use in quantum algorithms will actually require upwards of 1,000 physical qubits. Other experts have “suggested that quantum error correction could even be fundamentally impossible, though that is not a mainstream view.”

But what if effective QEC codes are introduced? What are the possible applications of scaled-up quantum computers containing a large number of qubits if scientists devise ways to neutralize the effects of quantum noise and prevent quantum decoherence from destroying the information encoded in superposed, entangled quantum states?

There are two general categories in which quantum computers really could significantly outperform classical computers, one of which we have already mentioned: factoring large numbers, which is fundamental to the cryptographic infrastructure of our world today. The second category is simulating quantum systems, which may not sound especially important, but it has major implications for several multi-billion-dollar industries. Since the first category mostly concerns how quantum computers might threaten or undermine modern societies of the Digital Age, we will discuss it in the next section, focusing here on category number two.

There are only two general areas that quantum computers could vastly outperform their classical counterparts: (1) simulating quantum systems, and (2) breaking the public-key cryptography that underlies almost all communications on the Internet today, by solving the factoring problem.Simulating Quantum Systems Using Quantum Systems (i.e., Quantum Computers)

Because of phenomena like superposition, interference, and entanglement, quantum systems are extremely complex. This makes them very difficult to study using classical computers, as the number of computational steps required to simulate such systems grows exponentially with the system’s complexity. For example, if one wants to study a quantum system consisting of 100 atoms, one would need some 2^100 numbers just to describe that system (see the video below).

But, crucially, recall that n qubits is equivalent to 2^n classical computational steps. What, then, if we were to use quantum systems themselves — in the form of quantum computers — to simulate quantum systems? Suddenly, the challenge of simulating and thus studying quantum systems becomes computationally feasible.

The implications of this go far beyond the scientific aim of understanding the fundamental nature of the universe — quantum mechanics. If we can simulate chemical reactions that depend on the quantum properties of particles, then we could predict the result of novel chemical reactions without having to perform real-world experiments involving those chemicals. In this way, quantum computers could have huge implications for material science, the development of new fertilizers, and the design of new pharmaceuticals, potentially boosting the profits of companies that design and manufacture these things by many billions of dollars. Perhaps quantum computers could enable the discovery of new treatments for or diagnoses of diseases like cancer, multiple sclerosis, and Alzheimer’s. Big if true, as they say!

Consider a 2022 paper published in PNAS, which focuses on a class of enzymes called “cytochrome P450.” Enzymes are the proteins that catalyze the chemical reactions in our bodies. Cytochrome P450, in particular, is responsible for metabolizing within our bodies “70-80% of all drugs” prescribed in clinical settings. It does this through an oxidative process that “is inherently quantum.”

Consequently, the enzymatic transformation of drugs in our bodies is very difficult to simulate using classical computers, given the exponentially growing complexity of quantum phenomena. The authors of the PNAS paper, however, report that a quantum computer consisting of a few million qubits could more quickly and accurately simulate cytochrome P450 than even the very best classical supercomputers. “We find that the higher accuracy offered by a quantum computer,” they write in a blog post, “is needed to correctly resolve the chemistry in this system, so not only will a quantum computer be better, it will be necessary.”

By running simulated models of molecular processes with quantum properties using quantum computers, pharmaceutical companies could develop novel drugs much faster and for far less money, which could greatly accelerate the discovery of new treatments for a range of diseases.

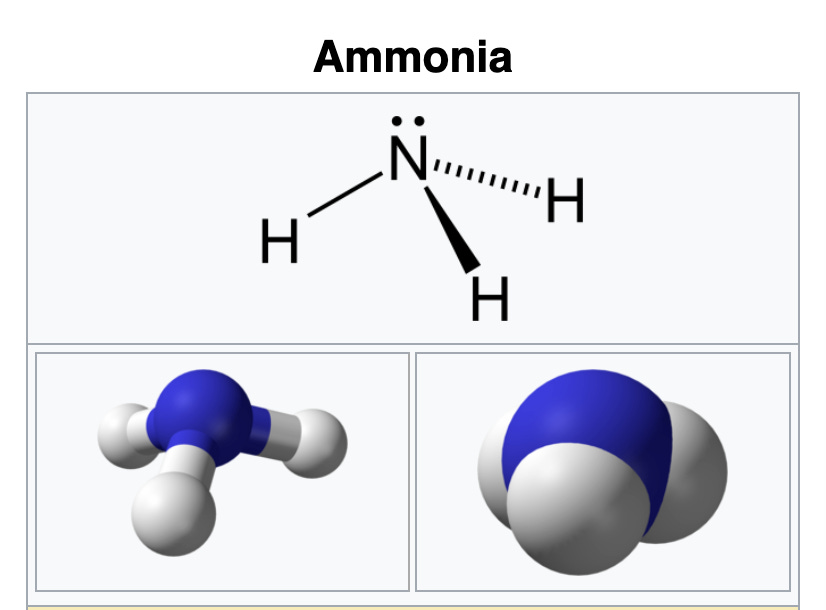

Or consider that about 1/3 of the food produced around the world today involves the chemical compound ammonia, which consists of one nitrogen atom and three hydrogen atoms, as seen below:

There are two common uses of ammonia within the agricultural industry: either as a plant nutrient that is applied directly to the soil, or as the basis for synthesizing other nitrogen fertilizers. Although ammonia occurs naturally, the industrial manufacture of ammonia uses the so-called “Haber-Bosch process,” which requires large amounts of energy to produce the high temperatures and pressure necessary to take nitrogen from the atmosphere and combine it with hydrogen atoms, thus yielding ammonia.

However, there is another way to produce ammonia, via an enzyme called “nitrogenase.” This alternative approach doesn’t require high temperatures or pressure, and hence is much less energy-intensive.

The problem is that producing nitrogenase itself is “a complicated catalytic procedure that today’s computers cannot handle,” since it “involves molecular modeling where nitrogenase is mapped by traversing the path through nearly 1,000 atoms of carbon.” Classical computers alone are not powerful enough to simulate this process, but a team of scientists at ETH Zurich and Microsoft Research reported in 2017 that a classical and quantum computer working together could successfully achieve this. As Matthias Troyer notes, if “you could find a chemical process for nitrogen fixation that is a small scale in a village on a farm, that would have a huge impact on the food security.”

In other words, quantum computers — paired with classical computers — could have major consequences for food production by enabling the production of ammonia through nitrogenase, rather than the far more costly and difficult Haber-Bosch process.

Other potential uses of quantum computers include modeling fusion reactions, facilitating high-speed financial transactions, managing stock-portfolios, and perhaps accelerating progress in the field of machine learning (ML). However, it is worth emphasizing that, as Edd Gent writes in an IEEE Spectrum article, “even in the areas where quantum computers look most promising, the applications could be narrower than initially hoped.”

For example, quantum computers are expected to provide only modest speed-ups on a variety of optimization problems, and, as noted earlier, there is an entire class of computational problems — the NP-complete problems — that quantum computers will almost certainly be unable to solve, just as classical computers cannot solve them.

There are, once again, only two general areas that quantum computers could vastly outperform their classical counterparts: simulating quantum systems and breaking the public-key cryptography that underlies almost all communications on the Internet today. Let’s now turn to this second issue.

The RSA Cryptosystem, the Factoring Problem, and Quantum Computers

RSA encryption involves sending a very large number, from one computer system to another, that must be factored into two prime numbers, as explained below:

As we saw above, this is an NP-problem that falls into neither the NP-complete nor P classes: classical computers can verify whether two prime numbers equal the larger number of interest efficiently (in polynomial time), but they cannot efficiently solve the problem of breaking this large number down into its prime factors.

Quantum computers, on the other hand, can do this using Shor’s algorithm — a quantum algorithm that, as such, cannot be run on classical computers. Consequently, any personal information, financial data, medical records, and so on, that are transmitted over the Internet could be intercepted and read — even if encrypted by the RSA system. Yikes!

The implications of this are quite staggering, as Shor’s algorithm will result in the entire cryptographic infrastructure upon which the modern Internet is based collapsing. Many geopolitical actors are thus racing to acquire as much RSA-encrypted information about their adversaries as possible, based on the belief that quantum computers will someday enable them to actually read this information — a strategy known as “store now, decrypt later.” As the former US National Cyber Director, Harry Coker, observes, “this endangers not only our national secrets and future operations but also our economic prosperity as well as personal privacy.” The day that quantum computers enable all RSA encryption to be cracked has been dubbed “Q Day.”

However, scientists are actively working on quantum cryptography methods, such as quantum key distribution, which would exploit the aforementioned no-cloning theorem to ensure that information exchanged between two parties cannot be read by others. The situation can be summarized as follows: quantum computers will cause a major headache for companies and states, but ultimately we expect quantum cryptography to replace RSA encryption, thus enabling the secure transfer of information. One giant leap backwards, one giant leap forwards — although, as noted above, there may be information being transferred right now, using RSA encryption, that third parties could read in the future. That could still be bad.

In 2019, a team of scientists at Google announced in the journal Nature that they had achieved quantum supremacy. This term was introduced in 2011 to “characterize computational tasks performable by quantum devices, where one could argue persuasively that no existing (or easily foreseeable) classical device could perform the same task, disregarding whether the task is useful in any other respect.” The Google team designed a problem that would be especially difficult for a classical computer to solve, and then showed that a Google quantum computer called Sycamore could solve it many orders of magnitude faster. In particular, they write:

Here we report the use of a processor with programmable superconducting qubits to create quantum states on 53 qubits, corresponding to a computational state-space of dimension 2^53 (about 10^16). Measurements from repeated experiments sample the resulting probability distribution, which we verify using classical simulations. Our Sycamore processor takes about 200 seconds to sample one instance of a quantum circuit a million times — our benchmarks currently indicate that the equivalent task for a state-of-the-art classical supercomputer would take approximately 10,000 years. This dramatic increase in speed compared to all known classical algorithms is an experimental realization of quantum supremacy for this specific computational task, heralding a much-anticipated computing paradigm.

Google’s claim of achieving quantum supremacy has been controversial, and indeed Google’s rival, IBM, has argued that “Google had exaggerated its quantum computer’s advantages and that quantum supremacy wasn’t a meaningful achievement anyway.” Nevertheless, it does appear that building a quantum computer that exponentially outperforms classical computers on certain tasks is a matter of “when” rather than “if.”

Another notable development is the creation of quantum computers consisting of a large number of qubits. As noted above, Google’s Sycamore computer contains 53 qubits, though other quantum computers have recently been built with far more. For example, in 2023 the company Atom Computing built the first quantum computer with over 1,000 qubits — more than twice as many qubits as IBM’s Osprey, which previously held the record. Atom’s computer has 1,180 qubits, whereas Osprey had only 433. However, IBM also unveiled another quantum processor (a type of chip) in 2023, called Condor, that contains 1,121 qubits, and it announced that same year that it aims to build a 100,000-qubit device by 2033 (citation here).

The size of these computers, though, should not be interpreted as indicating that they are more useful. Due to quantum noise and decoherence, the error rate of Condor is five times greater than the error rate of IBM’s much smaller computer processor called Heron, which contains just 133 qubits. Consequently, in its next-generation quantum computers, System Two, IBM will use the Heron rather than Condor processor: though much smaller, the Heron processor is significantly more accurate. As quantum error correction codes become more powerful, the usefulness of these large-qubit processors will increase. As Wired wrote last year, “The Quantum Apocalypse Is Coming. Be Very Afraid.”

Summary of Chapter 3

So, there is a great deal of hype surrounding quantum computing. Many of the boosterish claims made in popular media articles are misleading, as the potential uses of quantum computers — so far as we know right now— are quite limited. However, the ability of quantum computers to simulate quantum systems exponentially more efficiently than classical computers could have profound implications for multi-billion-dollar industries, including the pharmaceutical and fertilizer industries. Quantum computers could also facilitate significantly better diagnostic methods by enabling scientists to process information and perform calculations much faster than classical computers.

At the same time, quantum computers also pose several dangers, the most conspicuous being that it could render the most widely used public-key encryption systems today — the RSA cryptosystem — completely useless. While scientists expect quantum cryptography to solve this problem, the “store now, decrypt later” strategy employed by many geopolitical actors could have harmful consequences in the future for states, companies, and even individuals.

Perhaps the most exciting possibility — from a purely academic perspective — is the possibility of learning more about the fundamental quantum nature of reality by studying quantum systems using quantum systems. There have not been any revolutionary changes to our understanding of the universe since the early twentieth century, when Albert Einstein introduced his theories of special and general relativity, and quantum mechanics was proposed by physicists like Werner Heisenberg and Erwin Schrödinger. Maybe quantum computers will crack open the door to a new, currently unimaginable paradigm in physics.

Conclusion

Thanks so much for reading! I hope you got something out of this. I had several quantum physicists and quantum computing experts look over the article to ensure everything is accurate. Everyone gave it the thumbs up! No doubt there are still some errors, as I’m epistemically trespassing on property owned by quantum physicists, and I am but a lowly philosopher. :-) If so, they are my fault, not the reviewers’. :-)

Wishing everyone all the very best in these tumultuous times. As always:

Thanks for reading and I’ll see you on the other side!

It’s also a good time because I’m moving to a new city. Spent the last month in Lisbon (Portugal), Toulouse (France), and Perpignan (France). Here’s a few pictures I took of the Pyrenees mountains on my daily run! :-)

This article was adapted from a report I published with the Inamori International Center for Ethics and Excellence at Case Western Reserve University.

Great explanation. Thanks for that !

A bit of history: 1st: ‘computers’ were people trained to solve complex problems (see movie “hidden figures”) 2nd: computers used to be big and expensive. They needed specially trained people to operate them. Then came mini-computers which took up less space, but had limited function and were used to control machines (look up Naked Mini). Then Intel decided rather than use a complex custom circuit to use a programmable system to, if my memory server, run a Mainframe disk drive. A couple of hobbyists wrote an article for Popular Electronics using that processor and a bunch of 100 pin connectors (because they found those on sale for the 50 or so kits they thought they would sell) They got a thousand orders within a week and the hobby computer craze started. A couple of kids in California though they could sell pre-built hobby computers for those who didn’t want to solder their own and allowed others to write programs for it (you may have heard of that company…Apple).

Up until this point if you wanted more than one person to have access to a computer (or wait in line for hours to access the mainframe, you had to connect using a simple keyboard and monitor setup.

While we now can have in our hands computers which are far more capable than the old mainframes there are somethings that your desktop can’t provide: reliability and scale. A computer center (whether its company owned, shared or a cloud center) has is redundant communications links, 24/7 power with regularly tested backups and the reliable hot swappable components. On a mainframe you can replace processors, memory , mass storage without shutting anything down. On a smaller scale, what looks like a tower computer, if its a server will have redundant power supplies, error correcting memory and mass storage which can support disk failure with replacement disk able to be swapped in and the system restored in the background. What happens when say the redundancy fails, major airlines have to stand down operations for several days. What happens if the bank’’s data center fails, all their ATMs stop issuing money.